Even an Advance Warning Didn’t Save Cyclist’s Life

“After a Seattle bicyclist died from a fall down some stairs near a poorly marked bike path,” begins the Seattlepi.com story, “a city transportation official said his department had not received any complaints about the stairs before the death.”

Vivace’s Brian Fairbrother crashed on some hard-to-see steps near 1177 Fairview Avenue North around 6 p.m. on August 30, 2011. He was removed from life support on September 8.

But Michael Hoffman, a 31-year-old scientist at the University of Washington, provided Seattlepi.com and The SunBreak with an email he sent to the City of Seattle’s Parks Department in 2008, after he rode the newly completed Cheshiahud Lake Union Loop.

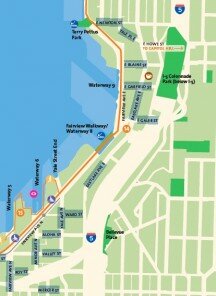

Some commenters on my earlier post (“Did a Bike Path Just Kill a Seattle Cyclist?“) took issue with the term “bike path,” since the stretch in question is clearly a sidewalk with no particular work done to make it more or less safer for bikes. But the City publicizes it as part of a “multi-use loop” and if you look closely at the map of the loop, those are little blue bicycles riding along…a sidewalk. Clearly, the map is not the territory.

As the Parks Department had put up a sign soliciting feedback, Hoffman responded with an alarming prescience:

It was nice ride in general but there were a few places that were a bit confusing or even dangerous for an unfamiliar rider. I’m not sure if the loop is considered finished yet but I thought these comments might be helpful. [...] There is a bit on the east side where the trail seems to go down a lot of steps and then back up. It is not apparent until you are near the steps that they are actually steps rather than a ramp. I think this is dangerous currently. I would strongly recommend some warning signs here. If cyclists are meant to instead travel on the nearby road against the traffic flow, the trail needs signage and road markings to indicate this.

David Graves, a senior planner with Seattle Parks & Recreation, wrote back, saying: “Due to the traffic flow, the counter clockwise direction is more challenging to navigate on a bicycle than clockwise! As we work on drafting a Master plan for the loop, we will keep your comments in mind.”

When I first asked Seattle Department of Transportation spokesperson to comment on this, she referred me to Parks spokesperson Dewey Potter. Potter confirmed via email that Hoffman’s comments had been received and shared with SDOT:

It was one of many comments received during that process. Parks did share it with SDOT, as the planning team included staff from both departments. It is my understanding that SDOT intends to install signage at the site next week…

Signage is better than the nothing SDOT provided for the past three years, but if the City is going to prompt cyclists to ride on a sidewalk, there are also safety gates that let pedestrians pass but prevent bicycles from riding into danger zones. (It probably wouldn’t hurt to slow down runners and inline skaters as well.)

One of the odd disconnects that still separates car drivers from cyclists appeared in comments on my original post. Was Fairbrother wearing a helmet? (He was.) Was perhaps a 50-year-old man on a road bike trying to jump a flight of stairs? (It seems unlikely.) Why wasn’t he paying closer attention? (This is a question Buddha has asked all of us. I ask it every single day of car drivers on their cell phones.)

The disconnect is how easy it is to use bikes to get around, as a form of urban transportation, rather than a slow and sweaty way to annoy car drivers in a hurry. When you bike to get from Point A to Point B, you often just put your head down and go. That being the case, cyclists, just like any other human being, tend to rely on infrastructure’s coherence for safety.

This part of the loop is missing the equivalent of a Wrong Way – Do Not Enter sign. That’s all there is to it. But the larger lesson is that our current infrastructure promotes a cage-match atmosphere. Every time a cyclist is directed by sharrow to “take the lane” on a thin uphill street, car drivers line up fuming behind.

You could ask the drivers exactly how much time they’re losing over a single block, moving at 5 mph instead of 30, but that, while perhaps of rational interest, is not the issue. That infrastructure is creating a problem where there wasn’t one. No one drives an arterial to go slower than on a regular city street. If, because of hills, bikes are going to slow traffic dramatically, SDOT can’t simply throw paint at the problem–you can’t paint over anger and frustration, and its tendency to fasten onto a nearby visible object.

Seattle Transit Blog, calling for bike boulevards, cuts right to the heart of the problem:

Seattle is killing people on bikes at the rate of 1 per month, and we seem more interested in discussing the behavioral problems of people driving and cycling rather than addressing the structural problem, the underlying safety of our transportation network. Given the fallibility of human behavior and the assurance of operator errors, we would be wise to reduce structural risk rather than rely on educational campaigns.

In his post on improving road safety, Mayor McGinn echoes the sentiment:

It’s time to stop finding fault with each other, and to start finding a remedy. There has been a lot of overheated rhetoric about cars versus bikes or bikes versus cars, and it’s not helping make our roads any safer. It’s not even accurate. Most people who ride a bicycle also own a car. Drivers will also park and walk across the street or on a sidewalk to get to their destination.

Seattle Bike Blog argues, simply, “We have reached a turning point in Seattle bicycle safety.” I certainly won’t begrudge anyone who’s lost someone in an accident their righteous anger, but I empathize more with Tom Fucoloro’s faith that “we can do better.”

This summer’s disturbing cyclist death toll is notable for the ways in which our new bicycling infrastructure has failed us–all of us. I can’t imagine what a driver feels replaying that instant a cyclist seemed to come out of nowhere. This leaves everyone on edge. So let’s not delay rethinking what is proving to be a dangerous and divisive primary mode: putting bikes in the road with cars, with bike lanes, sharrows, and taking a lane appearing as options willy-nilly.

As Seattle Transit Blog’s Zach Shaner writes, “In Seattle we may lack many things, but we have an abundance of quiet, low-traffic streets directly adjacent to our busiest arterials. We should put them to better use and save a few lives.”

Daily Email Digest of The SunBreak

Daily Email Digest of The SunBreak