Donald Byrd on the Miraculous Mandarin in All of Us

In previewing Spectrum Dance Theater’s upcoming, free-to-the-public presentations of The Miraculous Mandarin, by Béla Bartók, I discovered that the Mandarin in question was going to be danced by Donald Jones, Jr., and got in touch with Donald Byrd to find out if he meant anything by that. It’s better to ask, with Byrd, because he tends to provoke both intentionally and unintentionally, as audiences at the 5th Avenue Theatre’s Oklahoma! discovered recently.

There, the casting of a black actor as Jud (Kyle Scatliffe) raised eyebrows all over town. At a TEDxTacoma talk afterward, Byrd spent some time unpacking that reaction, beginning with the basic assumption that everyone in Oklahoma was white. (In the early 20th century, black settlers streamed into the Oklahoma and Indian Territories–the territories weren’t combined to form a state until 1907 but it was still better than Kansas. There were even discussions about whether the new state would be majority black. The musical is set in 1906, the last year of Territoryhood.)

For The Miraculous Mandarin, Byrd insisted, it’s just a case of casting the right person for the role. “It’s mostly not done with an actual Chinese person, anyway,” he told me on the phone. “It’s more about it [the role] being coded for ‘outsider’ or ‘Other.’ He’s just different. Something else,”–besides skin color–”will bring his otherness out.” You’ll have to go see to find out what that is.

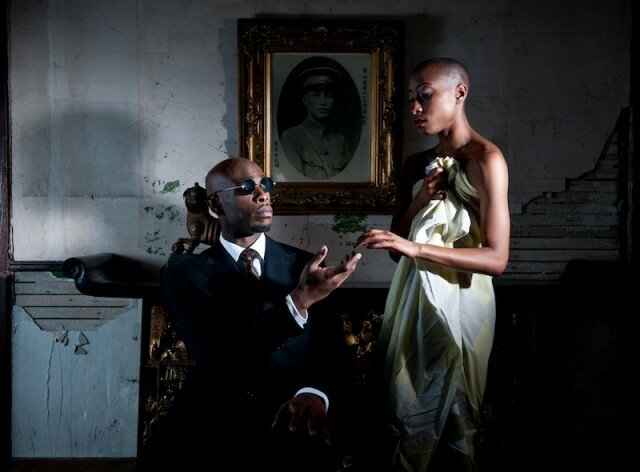

Jones will play opposite the equally striking dancer Jade Curtis; because both are black, that frees Byrd up to explore more than differences in skin hue. The Mandarin, he said, is “a man of means, entering a shadowy world. He’s not part of her reality,” referring to Curtis’s character, who is used as sexual window-dressing by robbers. It’s as much about the entrances and exits created and denied by class, as it is about the treatment of a foreigner, argued Byrd, noting that the Mandarin of Bartók’s era would still have been a moneyed, powerful man, if exotic to Europeans.

That said, you will still get Mandarin Chinese–Byrd intends to include a prologue and epilogue spoken in a dialect of Mandarin, and chortled when I asked if it would be translated. (No chance.) I think it’s fair to say that Byrd likes to complicate the apparently simple, to set ideas and perceptions caroming off each other. By frustrating the easy, direct conclusion, he fosters the oblique association, usually a series of them.

When he sets something like the Miraculous Mandarin in Chinatown’s Hing Hay Park, he’s not conflating historical bits and artistic pieces into an amalgamated Chinese identity (speaking of coded “outsiderliness,” Hungarian Bartók would have been accent-on-the-Eastern European), but keeping alive salient, sometimes uncomfortable differences. All of it is charged by the limits of the artistic frame; qui est in, et qui est out. At Hing Hay Park, the framing device is a literal window frame, the audience outside looking in.

“It’s a little like Rear Window,” explained Byrd, referring to the Hitchcock film that made voyeurism as American as spied-on apple pie. “What are you seeing, what are you missing? Can you believe it?”

All shows begin at 8 p.m., over two weekends: May 17-19 and May 24-26. While the show is free, you probably want to get a ticket in advance, to reserve your seat.

Daily Email Digest of The SunBreak

Daily Email Digest of The SunBreak