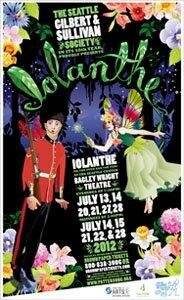

One of Gilbert & Sullivan’s comic masterpieces, Iolanthe, returns this July to the Bagley Wright Theatre (July 13 through 28; tickets), and to the repertoire of Seattle Gilbert & Sullivan Society for the first time since 1997. This absurd and delightful show comes close in audience affection after the three most popular of the canon, H.M. S. Pinafore, The Mikado, and The Pirates of Penzance, and gives plenty of room for the presenters to allow their imaginations to bloom.

One of Gilbert & Sullivan’s comic masterpieces, Iolanthe, returns this July to the Bagley Wright Theatre (July 13 through 28; tickets), and to the repertoire of Seattle Gilbert & Sullivan Society for the first time since 1997. This absurd and delightful show comes close in audience affection after the three most popular of the canon, H.M. S. Pinafore, The Mikado, and The Pirates of Penzance, and gives plenty of room for the presenters to allow their imaginations to bloom.

The music is entrancing, the political satire delicious and always with topical allusions. (I can’t imagine there won’t be a reference to the health care law this time).

In it, the British peers insult the Fairy Queen and her band. In revenge the fairies cast a spell which requires the Lords to think for themselves and not vote along party lines. (It may have been written in 1882, but part of G&S’s charm is that it is is always politically pertinent!)

Iolanthe of course contains all the G&S stock characters including the gentleman who sings pattersongs. Seattle G&S is fortunate to have two singers who are as good at this as any I have heard in many decades of G&S attendance: Dave Ross and John Brookes have that essential dry baritone and ability to get tongue-twisting words out clearly.

This is an entirely new production. The company has no room to keep all its sets so builds most things fresh every time. Like so many small businesses based in South Lake Union, Seattle G&S had to move from its long-time quarters but had the luck to find more spacious digs with a long lease at the old Crown Hill Elementary School. There a swan, a huge Japanese urn, and some ominous-looking wheels from the Tower of London share a roomy, lightfilled space with a half-painted bridge, a bunch of railings with an emblem denoting the British House of Lords, a piano, racks of costumes topped with a row of cannon, stacks of paint pots, plus much else.

Officially, this is an amateur group, but any organization which has been running for 58years has found a modus vivendi that works for it, and its methods and decisions are exceedingly democratic.

As set designer Nathan Rodda says, “There are always boundaries. We step over them all the time, but so long as we understand where the boundaries are, I think the best ideas come when people do cross boundaries. I don’t care where an idea comes from.”

Next year’s opera gets decided on about a year ahead, says producer Mike Storie. The board has informal meetings in the fall and winter. They acquire videos of professional and amateur productions from around the world, check them out to see what they think worked and what didn’t, and gradually the bones of the production jell.

Once general outlines are decided, Rodda makes sketches of his set ideas and brings them to Storie and stage director Christine Goff. If they approve he goes straight to working drawings.

In professional companies, it is quite common “for the designer to do very elaborate drawings, and perhaps a model, and then go away,” says Rodda, “and it’s up to the painters and carpenters to generate the working drawings and complete it. Normally all the scenic artists own are their brush strokes.”

Rodda, however, doesn’t disappear and because he’s building it, he doesn’t need to do all that. He’s there, hands on, throughout the process. “Because I’m going to execute it, I design to my strengths,” he says. He began painting scenery in high school, and became a free-lance architectural and theater designer. He’s been with Seattle G&S since 1989, first as a tenor, and after 1997, as scene designer though he did some scene painting before that.

He values his stint as a singer, and sometimes now he is a supernumary. “It’s useful to get some stage experience if you want to be an effective designer,” he says. “You have to understand the issue actors have, see things from the perspective of the director, and be mindful of their turf as director.”

Rodda is a painter first and foremost, but he has a skillful team with which to work. Master carpenter Gary Webberley has been with the company since 1966, and according to Rodda, understands “just how strong a bridge must be to hold 1,600 pounds of beef running across while singing.”

Michael Crow is his assistant, while Mike Andrew carves, and props master Marv Brown creates such items as fairy wings and wands that light up, as well as special wands for three fairy klutzes—watch out for them! All have also ended up on stage as singers or actors in some role or other. This year, Rodda has an intern, Erin Yoshida, a theater major between her sophomore and junior year at UW. “It’s nice to have a young assistant,” says Rodda. “Her brain works faster than mine, and her minor in Math is useful, too.”

Research is essential, even for a comic opera. Seattle G&S has a stored Big Ben (the clock in the tower which is now to be called the Elizabeth Tower) Rodda would like to use with his House of Lords, but to work for the actors it would have to be on the wrong end of the Houses of Parliament, which would make the action take place in the midst of the river Thames. He knows he would hear about it. So, no Big Ben. “I’ve had amazing letters […] someone wrote to say the signal flags in H.M. S. Pinafore said something incorrectly!”

There’s a device on the gates to the House of Lords, and that has to be accurate also. It’s a portcullis with a crown on top, so that’s what will be there on stage.

An enormous amount of time gets devoted to each annual production, but everyone associated with Seattle G&S has got hooked. Some, like Webberley and Storie have been there for years wearing different hats. Quite a few are well into retirement years, though newcomers are joining in all the time. No one gets paid a living wage (though the office manager gets a half-time salary), and regular hours are a joke. “We get what we call ‘insults,’” says Storie. “I make about 80 cents an hour. Mike Andrews is a janitor. He works until midnight, then comes in to carve, and we frequently find him asleep in the morning. Now he even has a bed!”

Last Friday, no one was going to bed. It was load-in night, when scenery, props and all were loaded into trucks for schlepping to the Bagley Wright Theatre, where they were unloaded Saturday, to sort out all the hitches and glitches of scene changes, pit-building, lighting, sound details and rehearsal, and be in readiness for their opening night performance on Friday, July 13. Given their experience, despite the date, it should go like clockwork.