College tuition costs increase so rapidly they’re outpacing descriptors — “skyrocketing” was last decade, and they’ve been compounding yearly since. College tuition costs are so bad, in fact, that in mid-February the Seattle Times editorial board weighed in in favor of at least a temporary tuition freeze at state schools. (“The average Washington student debt upon graduation in 2011 was $22,244, according toprojectonstudentdebt.org, a nonprofit independent research initiative,” noted Spokane’s Spokesman-Review around the same time.)

College tuition costs increase so rapidly they’re outpacing descriptors — “skyrocketing” was last decade, and they’ve been compounding yearly since. College tuition costs are so bad, in fact, that in mid-February the Seattle Times editorial board weighed in in favor of at least a temporary tuition freeze at state schools. (“The average Washington student debt upon graduation in 2011 was $22,244, according toprojectonstudentdebt.org, a nonprofit independent research initiative,” noted Spokane’s Spokesman-Review around the same time.)

At the time, the Times editorial board felt there was good news in the offing:

Two bills in the state Senate, one providing $225 million to the six public four-year institutions, the other $188 million to the state’s community college and technical schools, sets a framework for the state eventually to get back to paying for at least half the cost of education.

But with Washington State facing a $1.3-billion budget deficit, the Times‘ Katherine Long reports, the mood has changed substantially at the Capitol:

“Conversations have gotten increasingly pessimistic,” said Margaret Shepherd, director of state relations for the University of Washington. “Legislators are telling us no new cuts would be a victory.”

Long quotes Shepherd as predicting state schools will raise tuition by “somewhere between 5 to 7 percent to meet basic needs.” That’s supposed to be heartening, in that recent increases have been double digits. Even so, it won’t derail in-state tuition at top public schools from cresting $20,000-per-year within a decade. (The University of Washington’s “budget-minded price tag” for in-state students, if you throw in room and board, books, and so forth, is more than $26,000 per year.) If differential tuition is adopted, where some degrees cost more, then the situation gets more complicated.

The gloomy news from the state capitol comes on top of cuts in education funding from federal sequestration. The National Education Association broke out estimated cuts by state; funding for work study nationally is on the chopping block, and in Washington that affects more than 8,000 students.

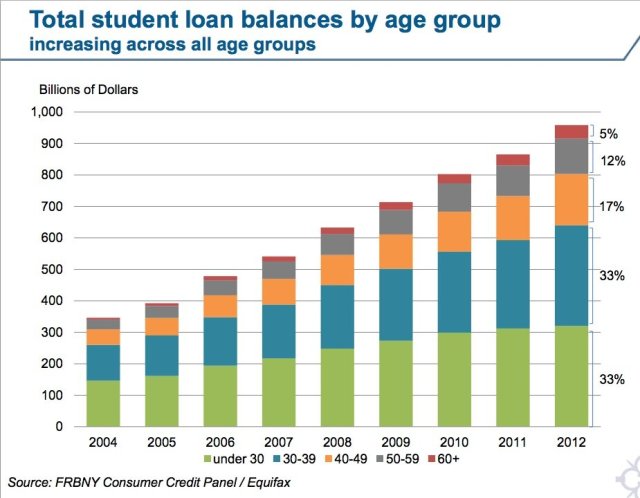

None of this will slow student loan debt, which nationally reached $966 billion at the end of 2012, topping all other forms of household debt except for mortgages, according to the New York Fed. To reach that amount, it tripled in size over the last eight years with no trace of a Great Recessionary slowdown. 42 percent of 25-year-olds have student debt now, and 17 percent of the total 6.7 million borrowers are 90 or more days delinquent. (If you exclude borrowers in deferment or forbearance, then the delinquency rate tops 30 percent.) The preceding figures are from a special student loan report for the New York Fed (pdf).

Previously, we asked an economist to explain the increases in tuition costs: “there’s a higher administrative cost. But I don’t think that explains the overall cost.” James Surowiecki of the New Yorker tried to pin some of it on stagnant productivity (one teacher can only teach so many students, at least until online teaching proves its worth). But as this report on spending trends between 1999 and 2009 (pdf) found, faculty compensation never exceeded 40 percent of education costs. (Non-faculty staff costs remained in the same range 30-to-40 percent range.)

As colleges and universities know, one professor can only teach so many students, but two part-time faculty can do the same job for less, and teacher’s assistants for even less than that. This dynamic has created downward pressure on existing full-time professorships, as the icing on the cake.

Looking into that report’s numbers, Felix Salmon notes:

Overall, if we exclude for-profit schools, which were a tiny part of the landscape in 1999, we have seen tuition fees rise by 32% between 1999 and 2009. Over the same period, instruction costs rose just 5.6% — the lowest rate of inflation of any of the components of education services. (“Student services costs” and “operations and maintenance costs” saw the greatest inflation, at 15.2% and 18.1% respectively, but even that is only half the rate that tuition increased.)

The other driver, Salmon, adds, is that states are consistently defunding public education. In Washington State, public universities demanded the ability to set their own tuition rates, as a way to make up for constant declines in state funding. (Conversely, Jordan Weissman argues in the Atlantic, if the federal government directed its financial aid strictly to public colleges and universities, we could return to an era of nearly-free higher public education. The Atlantic also has a handy graph comparing state defunding with tuition increases.)

But perhaps to the best way to explain tuition costs is to point to that nearly $1 trillion in student loan debt. Colleges charge more because students will pay it — or rather, they will borrow to pay it. Because of the non-dischargeable nature of student loans, students are approved for tens of thousands more than they would have been in decades past. Nothing seems more likely to stop the higher-tuition cycle than exposing the lie that originating student loans the size of home mortgages makes college affordable.

MVB, this is one of the most cogent articles I’ve ever read on college cost (a world I’m wholly immersed in through my day job). You are one of the only writers I’ve ever read who’s asked the critical question of WHY tuition costs what it does, rather than simply stopping at the “Yup, college is expensive” point. Thank you.

Thank you!