PNB Unveils a Giselle That’s Mainly Something Old

“PNB rethinks Giselle, giving it new life,” was the wishful title of Roger Downey’s preview of the Giselle reconstruction that’s being performed at Pacific Northwest Ballet (through June 12; tickets), but life is what the famous heartbreak ballet was missing, at least on opening night.

That makes this review of the world premiere a minority report–for the curtain call, the entire house seemed to rise for a standing ovation. (“Körbes’ performance—and that of the entire fine opening-night cast—seemed touched by magic,” says Moira Macdonald.)

Yet, to my eyes, much of the dancing was tentative, with notable exceptions: Carrie Imler, Jonathan Porretta. Porretta performed with such insouciance that it seemed like he could have been gripping a pipe between his grinning teeth as he guided Chalnessa Eames through her pirouettes. (In fairness to the rest, Porretta did have the luxury of “just” dancing–his part as a peasant dancer on opening night didn’t require any heights of characterization.)

The fine PNB dancers seemed not to have the choreography living in them yet, so they concentrated on performing the steps rather than their emotional expression. Even the orchestra led by Emil de Cou seemed less sure-footed when it came to tempi. In sum, there was much that was pretty (especially in Peter Farmer’s scenic and costume designs) and lowercase romantic, but not much truly Romantic, or as emotionally resonant, as you might hope.

The story of Giselle–it’s one of those wonderfully overwrought fables–is that a young peasant girl who loves to dance is wooed by a mysterious stranger, to the chagrin of the local game-keeper (a testy Batkhurel Bold, opening night). When her lover is unmasked by said game-keeper as slumming nobility–and out of reach–Giselle (whose health was never the best, we’re told, though it’s hard to believe of Carla Körbes) drops dead.

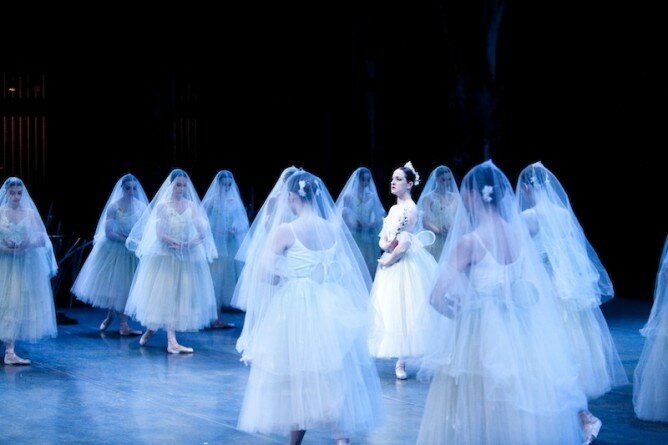

For Act Two, she resurrects as a member of a troupe of vengeful ghosts of young women dead before their wedding day, the Wilis. Her noble young man, tormented by her loss, is now tormented by the Wilis, and it’s Giselle’s final gift to him that he survives the test.

On opening night, Carla Körbes danced Giselle–surrounded by perky peasants, she was the perkiest, flirtiest one. Much of the story of the ballet is told through pantomime, which needs to appear as second-nature to the dancers as American Sign Language to the sibling of a deaf person. Körbes and her incognito Duke Albrecht (Karel Cruz) failed at that–their initial “meet-cute” had the subtlety of a billboard–but they did find in the choreography a fun, hand-snatching moment in which the payoff is that Giselle realizes the Duke is going to try to kiss her hand before you do.

Adolphe Adams’ score is enormously appealing. As PNB’s notes inform you, during the first act it’s high-spirited: “mostly in major keys, featuring waltzes and nineteenth-century hoedown music…”–except of course for Giselle’s “mad scene.” By Act Two, Adams tilts toward “unstable harmonies,” the “minor mode,” and spooky special effects of the day: “muted strings, tremolo, and harmonics.”

I find it a little fetishistic when, in the performing arts, the question becomes how a piece was performed 170 years ago, rather than what would help the piece communicate today. It is intellectually “interesting” to note the preponderance of dance movement below the waist, the flurry of steps, even the precision of ankle movement that Körbes displays, but no one but a balletomane, I think, will be mentally making the notes that You Dance Funny provides:

Major differences did show up, however, in additional scenes in Act II. Some productions of Giselle still do the scene with the hunters in the woods before they are scared off by the Wilis but probably not to this extent, and there is a second scene where a handful of incorrigible youths engaging in tomfoolery are warned by an old man of the Wilis, who they barely manage to escape from when the latter appear. [...]

In terms of fleshing out the plot my brain was telling me the Act II additions made sense, but in the end I found them problematic because they kind of marred the sanctity of the ballet blanc.

I may side with YDF on the issue of judicious editing–the bumptiousness of the yokels is what comes across, rather than any element of real fear. A special effect with the Wilis’ veils caused prolonged chuckling, which should be an indication that horror has not been struck. And de Cou kept the music moony and beautiful–only occasionally did it possess the driven, compulsive pace of someone dancing themselves to death, which is hypothetically what was occurring onstage.

While Cruz looked terrific in his agonizing series of entrechats, when he took a knee, his body never transformed into a bent bow of unrealizable longing. He remained someone resting on his knee. Even in his majestic lift of Körbes, who arches like a leaf in the air, it’s aesthetic, not unbearable. The person to watch then was Myrtha, “Queen of the Wilis,” performed impeccably by Carrie Imler as a mixture of gauzy white and steeled will. A curved foot looked like a scythe.

In the end, this is an almost supernaturally pretty ballet from PNB, but one that remains almost entirely in quotations, as if someone, preparing to tell you a story about what just happened, picked up a book and read from it instead. You may indeed learn something about the evolution of choreography from it–even love the choreography, for that matter–but not as much about young girls who like to dance, and why that leads to their deaths before their wedding day, why they rest uneasily, caught between love and vengefulness. There’s an answer there, but this Giselle dances away from it.

Daily Email Digest of The SunBreak

Daily Email Digest of The SunBreak