It’s a great weekend–and a great week–to be a movie geek in Seattle, with two of this ‘burg’s best independent theaters each unspooling movies that rightfully belong on any self-respecting film lover’s Bucket List.

The Grand Illusion Cinema celebrates the beginning of their eighth year as Seattle’s “weirdest, most wonderful non-profit, volunteer-operated cinema” with a party–and a screening of director Jean Renoir’s 1939 gem, The Rules of the Game tonight (the film will continue on for a six-day run at the GI). Renoir’s film follows a week in the country with several members of French aristocracy as various socialites (and their servants) dine, hunt, and carry on affairs.

The Rules of the Game is one of those rare vaunted Greatest Films in Cinema History that deserves its rep, richly. During its original release, it roused the undisguised contempt of the French upper class for its scalpel-sharp dissection of that strata’s lack of conscience. Critics at the time panned it, and the movie’s original negative was destroyed entirely during a World War II Allied bombing run (thankfully the movie received a painstaking restoration from surviving prints, to its full length with Renoir’s blessing in the late 1950s). But like a lot of misunderstood-at-the-time films, The Rules of the Game plays more resonantly now than ever.

This eighty-year-old movie courses with the sensibility of a contemporary indie flick. The gallery of characters–capricious socialite Christine (Nora Gregor), her equally fickle husband Robert (Marcel Dalio), and ostensible voice of reality Octave (well-played by Renoir himself), among them–initially feel like the kinds of archetypes that would pop up in a textbook Depression-Era American comedy. But instead of spinning these people into a rote pattern of irresponsible action/awakening of conscience/quaintly romantic happy ending, Renoir shows them yielding to their more base passions with frequent disregard for the emotional consequences. And with no Hollywood-style finger-wagging or manufactured repercussions for their actions, viewers are left to observe (judge) these people for themselves.

There are laughs and a lightness of touch, to be sure, but the movie’s also a layer cake of subtext. The hunting party scene in the film’s middle portion, which jarringly contrasts alluring tracking shots with a truly harrowing massacre of animals, is cogent semaphore for France’s denial of the horrors of World War II (and for that matter, the upper class’s pillaging of the resources around them). Meantime, the movie’s tragic coda furthers the metaphor of a county too wrapped up in its own hedonism to see the horrific writing on the wall. And if that’s not a lesson that could still use heeding today, I don’t know what is.

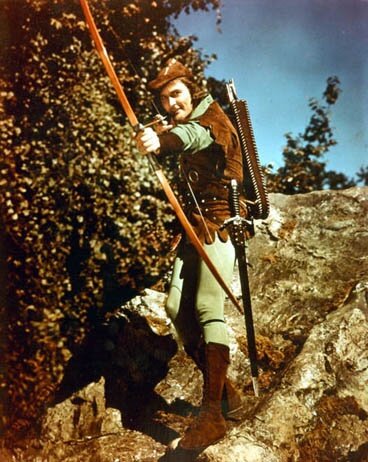

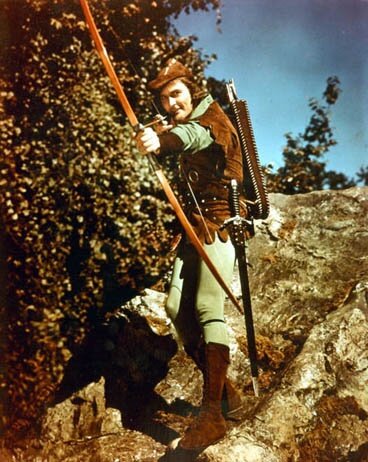

Central Cinema provides a terrific contrast to Renoir’s masterpiece by beginning a three-day run today of The Adventures of Robin Hood, the glorious 1938 adaptation of the well-worn English folk tale. No heavy message here, folks; just a rip-roaring great time.

Errol Flynn‘s megawatt charisma and raffish charm still define popular culture’s most heroic thief and archer; Olivia DeHaviland makes for the most gorgeous heroine this side of, well, anyone; great character actors (Claude Rains, Eugene Pallette, Alan Hale Sr.) enrich the proceedings stratospherically; and Flynn’s Robin Hood faces the most worthy of adversaries in the form of Basil Rathbone’s magnetically-sinister Sir Guy of Gisborne. See The Adventures of Robin Hood in all its breezily-perfect, eye-popping Technicolor glory on a big screen, and by comparison, today’s hollow action flicks will look like grunting cavemen in aluminum-foil diapers.