“I don’t think anyone celebrates my plots!” playwright Melissa James Gibson said in a Gothamist interview, adding, “I’m much more interested in where the characters lead me through their dialogue.”

Gibson’s play This (at Seattle Rep’s Leo K. Theatre through May 15; tickets) wants to be the subjective retelling of a woman’s life-stopping grief after the sudden death of her husband, a drawing-room dramedy about the ways in which adultery is like a traffic accident, and a story about how late-30s intimations of mediocrity variously affect the relationships in a social circle.

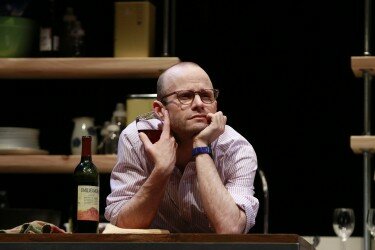

You might list its success in reverse order, thanks to the presence of Nick Garrison, who delivers an off-handedly stellar performance. I shouldn’t even say stellar, because it’s his understated pitch that helps him steal every scene he’s in, like Charles Grodin in Midnight Run. The rest of the cast is eminently capable, but Garrison is in a play of his own, deftly incorporating even total-recall capacity with world-weary charm.

This is much more funny than profound, which is not a criticism. Gibson’s strengths are her wry sense of humor, the anthropological intensity of her observations of (in This) 30-something life, the ease with which her characters spin out dialogue that’s a hybrid of mumblecore and Whit Stillman.

Certain things are just right: The distancing generality of “this” (you imagine it with the encompassing hand gesture) stands in contrast to the hyper-verbal facility of the characters when discussing things that just don’t matter very much. Director Braden Abraham knows the indoor life of these people, and gradually, despite the theatrical evidence, you begin to discount that the stage is even there.

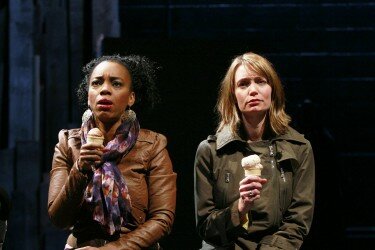

When the gang–poet Jane (Cheyenne Casebier) and gay lush-mnemonist Alan (Nick Garrison), and new parents Tom (Hans Altwies) and Marrell (April Yvette Thompson)–have Jean-Pierre (a terrific Ryan Shams) from Médecins Sans Frontières over, they skip right over his work for a witty, zing-y discussion of the qualifier “without borders.”A scene late in the play, where Jane and Alan argue over cultural appropriation is a wonderfully detailed time-waster.

Playwrights are rewarded who can “draw to life” in some way, capture a zeit’s geist, and Gibson is fairly praised for her accomplishment in this area. (This, when it opened in 2009, had Charles Isherwood calling it “the best new play to open Off Broadway this fall.”) Any 30-something who graduated with a liberal arts degree (i.e., the majority of the younger arts audience) can readily see their social circle in This.

However, the coconut is that cant about characters “leading” you anywhere, and the preciousness that arises from unearned poetry in theatre, when you must listen to the playwright vocalize.

Last point first, it’s the characters who are weak points in the play. Each seems to have gone to the same elocutionary school, to take classes in Unprompted Effusions and Advanced Repartée. Their behavior is precisely observed, but who they are is only partly filled-in.

As Tom, Hans Altwies devotes most of his stage time to sleep-deprived bickering with Marrell. The introduction of his class-consciousness early on has no payoff. He’s a wood craftsman–L.B. Morse picks up on this for his set, which features stacks of unused planks–but so far as the play is concerned, he could have been a pastry chef. Neither he nor Marrell seem particularly enthused about parenthood, which raises the question of why they have a child.

As Marrell, Thompson is equally a cipher, though she gets to sing and play the piano, which is actually a treat–she’s got quite a voice, albeit with a hint of Streisand. Jane is a poet who mainly, she says, proctors exams. (When Marrell says she’s too modest, Jane adds a superlative to her exam-proctoring.) Casebier struggles, I think, with diffident Jane, who doesn’t want to play games, or date the doctor Marrell has found for her. Without a sense of who Jane was before this, she’s mainly a wet blanket.

Amid all of this recalcitrance, there’s Garrison’s Alan whose roles during the play–funny drunk, gay “uncle,” willing ear, history verifier–illustrate his past life with the social circle. So when he decides that something’s got to change, and begins pushing for it, it’s both comic and a ray of light. Will he add an “l” to his name or go to Africa to save babies?

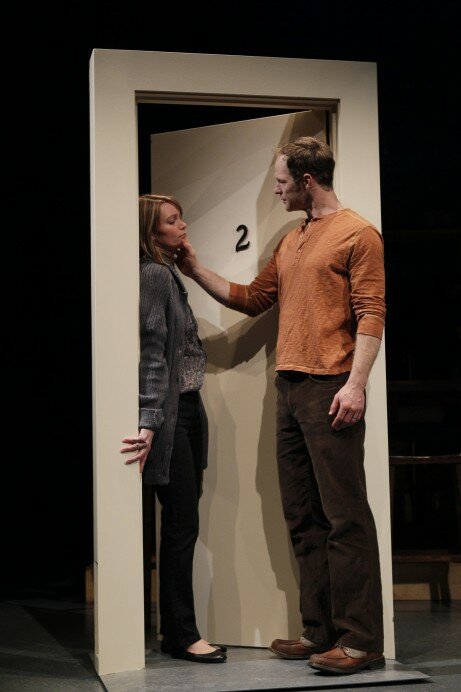

I don’t want to tell you the ending of This, because I didn’t like it and am trying to forget it. I wonder if it’s simply that plays like This can never reach a full stop. It’s a play that ought, if true to its characters, reject the cathartic, everything’s-gonna-be-different moment. L.B. Morse’s set features–besides a kitchen, living room, apartment, and piano nightclub–a number of doorways that people hang around in, emphasizing their inability to escape the liminal. They prefer the ambivalent space. It’s fascinating how the attraction to maintaining live options can leave you with none.

Finally saw this last night, really wished I didn’t. Seemed like a baby God of Carnage, which I couldn’t bear the second time through (of course the 1st time was with the great original Broadway cast, so that was a pretty high bar). Other thoughts –

The doorways were incredibly distracting. I learned that there are 3 brake mechanisms for the door, and each must be disengaged, then re-engaged for each change. I shouldn’t know that.

Alan seemed to me a stereotypical self-loathing gay character right out of the 60s. Ugggh.

And one clue for upcoming playwrights – when you’ve set up a trivial situation and made us all suffer through it for over an hour, do NOT deliver a punchline that pronounces the whole think ‘dinky’. We know that already, and it ain’t that funny.

The brake systems for the doors were really over the top. That was a little insane.

I didn’t feel like Alan was self-loathing for being gay–he was self-loathing for being full of potential and squandering it. That’s a huge difference. The mnemonist part seems more out of the ’60s.

Fully agree on the last point.