Remember Seattle’s cold, wet spring? Well, it wasn’t just us.

The Weather Underground’s meteorologist Jeff Masters has posted a La Niña wrap-up for you: “U.S. had most extreme spring on record for precipitation.”

While the driest spring on record dessicated Texas, and one of the top-ten driest springs dehydrated New Mexico and Louisiana, northwesterners in Washington and Oregon were grumbling their way through one of the top-five coldest springs the region has seen in the last century or so. Washington was one of nine states deluged by the most precipitation seen in 117 years of record-keeping.

(If you factor in both temperature and precipitation, this was the fifth most extreme spring in the past 102 years, nationally.)

In contrast, our problems (a plethora of potholes, more hydroelectricity than we know what to do with) don’t look that bad:

Nature’s fury reached new extremes in the U.S. during the spring of 2011, as a punishing series of billion-dollar disasters brought the greatest flood in recorded history to the Lower Mississippi River, an astonishingly deadly tornado season, the worst drought in Texas history, and the worst fire season in recorded history.

Even for a La Niña year, this was unusual weather, not least because La Niña just wouldn’t leave. It persisted through spring, and so the “jet stream remained farther south than usual over the Pacific Northwest and Midwest, and blew more strongly, with wind speeds more typical of winter than spring.”

Thus, the South grew cotton-mouthed, while the Midwest saw cataclysmic collisions of cold and warm air, and torrential rains. (“Since global ocean temperatures have warmed about […] 1°F over the past 40 years,” writes Masters, “there is more moisture in the air to generate record flooding rains.”)

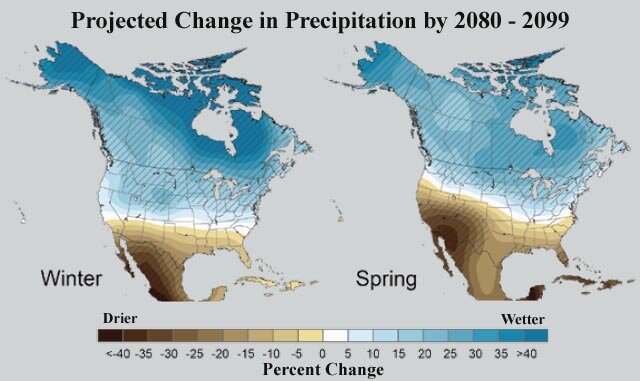

It’s ironic that while this kind of spring makes you suspect climate change is messing with the dials, as the image above illustrates, climate change models (at least) anticipate that the reverse would happen. The trend from from 1970 to 2000, notes Masters, has been for the jet stream to weaken and move northward (270 miles north). This spring’s jet stream, in both strength and position, was an outlier.

That said, Masters points out that this isn’t your father’s global atmospheric system any more: “recent record Arctic sea ice loss” may be causing atmospheric circulation changes in the Arctic Oscillation, pushing the jet stream southward “over Eastern North America and Western Europe during late fall and winter.” And again, it’s the warming temperature of the world’s oceans that helps increase the humidity of the air above them.

So you might call climate change, for better or worse, the wind at the back of what we’ve seen this year.