People more clued in than I will already know of singer-songwriter Josh Ritter, whose biography reads a bit like Doc Savage‘s: born to two neuroscientists in Moscow, Idaho, his first instrument was the lute. Glen Hansard invited him to open for The Frames, and in 2006, Ritter was named one of the “100 Greatest Living Songwriters” by Paste magazine.

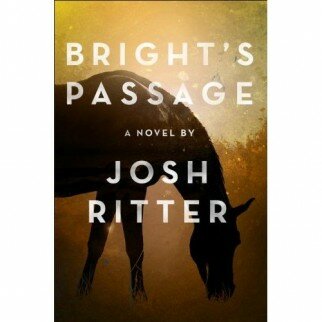

He’s now written a novel, Bright’s Passage, that Stephen King says “shines with a compressed lyricism,” and Robert Pinsky applauds for its “penetrating emotional colors. (He’s in town for a reading at Elliott Bay Book Company on Friday, July 15, at 7 p.m.)

The story of Henry Bright is told in three interleaved narratives throughout the novel: Henry’s West Virginia youth and his family’s feud with a neighboring Colonel, his time away in the trenches of the first World War, and his attempted flight from home upon his return, guided by a life-saving, horse-inhabiting angel he acquired during the War.

The story of Henry Bright is told in three interleaved narratives throughout the novel: Henry’s West Virginia youth and his family’s feud with a neighboring Colonel, his time away in the trenches of the first World War, and his attempted flight from home upon his return, guided by a life-saving, horse-inhabiting angel he acquired during the War.

From the opening sentence, when a baby is described as “a warm, wet mass, softer than a goat and hairier than a rabbit kit”–later it meeps and mews–there’s very little flatly told about West Virginia. Every word seems to have evangelical tongues of fire in it, and mud, and blood. It’s in the World War passages that a more terse poetry emerges:

They entered the War like men stepping out from beneath an awning into a torrential thunderstorm. The first man that Bright saw die fell back down into the very trench from which he’d just climbed. His uniform was still fresh and the tops of his boots had been shined. Only the soles looked muddy.

What war does to people and families is a fascination of Ritter’s–the neighbor Colonel’s sociopathic, martial airs infect Henry’s childhood, and his love. And Henry himself behaves like a wounded animal drunk on Revelation, the chapters on his experiences in the War interrupting like trauma flashbacks.

Ritter has clearly done his homework–his acknowledgements mention four books on World War I, not least of which is Tuchman’s The Guns of August–but in some ways the compelling specificity of his trench warfare fights the fable-like outlines of his story. It is strange that anyone who’s seen and survived what Henry has would be so unnerved by the Colonel and his two, on the evidence, idiot sons. It’s a question the Colonel himself raises about 100 pages in: “And anyway,” he asks, “how would you propose to kill Henry Bright, who has recently returned home from the War and is well practiced in the taking of life?”

In fact, Henry’s angel is more bloodthirsty than he is. Bright is so muddled between shell shock and his wife’s death in childbirth he can hardly distinguish between poison ivy and mustard gas rash, he stumbles forward with his babe in arms, and Ritter distracts you from nagging questions with a succession of people gathered at a hotel to evade the forest fire that Bright has set. One, Amelia, seems a little too glib and disparaging about her impending marriage; she confesses to Bright that she herself had been engaged to a Henry who went to the War .

He died. I was there with his family when the man came. He said that Henry–yes, that was his name, H., Henry: horrible isn’t it?–had perished a hero. ‘Perished?’ I asked the man. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Perished.’

It’s a reversal of Bright’s story, his counter-death, and it seems to have a salutary effect. Life is too hard in these pages to hope for much, but Bright, at the eccentric edge of his wits, may have arrested his velocity enough to be a father.