The sound of Russian voices pervaded the lobby at Benaroya Hall Wednesday night as the local community turned out en masse to hear the legendary Mariinsky Orchestra from St. Petersburg under equally legendary conductor Valery Gergiev on the Seattle Symphony’s Visiting Orchestra Series.

In the auditorium, the orchestra confirmed its stature as it performed a program of Russian favorites.

As a short opener, Gergiev chose three very different excerpts from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet Suites, with the leisurely “Friar Laurence” and quirky “Masks,” after which all hell broke loose in the fury (with alternating moments of peace) of the antagonistic “Montagues and Capulets.” This last sounded quite shocking in its vitality as the brass and percussion let fly but it was not loud for loudness’s sake. There were no moments of wanting to protect the eardrums.

Joining the orchestra for Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme, 18-year-old Belorussian cellist Ivan Karizna reminded this audience member of the young Lynn Harrell, another big kid with blond hair who plays his cello like an extension of himself creating miracles of breathtakingly beautiful sound.

Warm and open, somber or lively, light, dancing, floating or shimmering liquid gold, the gorgeous tones Karizna drew from his instrument were musically satisfying and technically excellent. The orchestra stayed closely supportive but never overwhelmed him.

Though the Variations were a pleasure to hear, the most profound moments of the program came with Tchaikovsky’s last symphony, No. 6, the Pathétique.

Gergiev’s interpretation of the first movement left one believing that it was the musical expression of the composer’s most painful thoughts. Agonizing conflicts and a plea for understanding needed only one’s imagination to hear them, and also the relief of the peaceful oases which occasonally came through.

Gergiev lightened the mood considerably in the second and third movements, Tchaikovsky’s brilliant waltz/two-step rhythm of the second with its irresistible melody, and the rushing anticipation of the jaunty upbeat march leading to its energetic peroration in the third. The sudden change of pace to slow and deeply somber pulled listeners up short, as the orchestra continued without a pause to the last movement, which almost seemed like a prayer of anguish, of crisis, of questioning Why me?, with again, a restfully serene melody interspersed.

Tchaikovsky, who died mysteriously nine days after the premier of this symphony, was a master of pacing his music so that it makes the utmost impact; and this was the most compelling, enlightening performance of this symphony this listener has heard over decades of concertgoing.

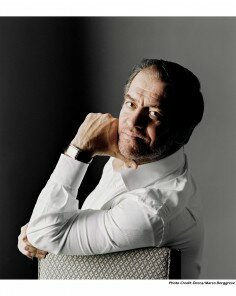

Gergiev, who conducted without podium and mostly without score, has a distinctive conducting style with fluttering fingers and not always a discernible beat, but his whole body, particularly in the Pathétique, conveys his intention to the musicians. They responded like a Rolls Royce engine to his every indication. The audience brought him back five times to accept applause with his musicians.