Somewhat disingenuously, I would think, Seattle Bubble’s The Tim is asking, in a post titled “Washington State Budget Woes: Where’s the Beef?” exactly why it’s so hard to make what look like incremental cuts. He’s not the only one, of course.

Last week, the AP’s Mike Baker wrote an article disputing Gov. Gregoire’s claim that she’s made $10.5 billion in cuts since 2008. On the one hand, Baker writes that hundreds of cuts “are simply automatic spending increases that didn’t end up happening.” That seems worthy of interrogation. But his claim that higher education wasn’t really cut because “lawmakers hiked tuition rates to offset the reductions” seems to misunderstand who pays tuition. Interestingly, the Seattle Times ran the story, then pulled it over what I’m told were concerns about “accuracy” and “completeness.”

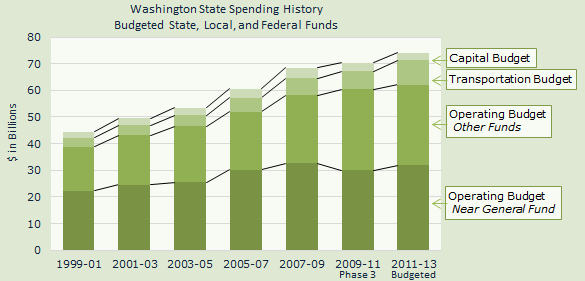

Back to The Tim. He provides a graph showing the state budget’s per biennium for the past decade, and notes what everyone else does who first comes into contact with the black hole of budgetary process: While Gregoire has been “taking an axe” to the budget the past few years, total spending has actually increased. “When the total budget is $74 billion, cutting $2 billion doesn’t seem like quite as big of a deal. We’re talking about 2.7% of the budget,” he argues.

I had the same reaction in my budget crisis post:

For the non-budget wonks among us, it’s hard to square cutting $4.6 billion out of the 2011-13 two-year budget, so that it still totals a staggering $32.4 billion, with the scorched earth that’s being reported: per the Seattle Times, say goodbye to the State Arts Commission and Tourism Office, the Basic Health Plan (an additional 66,000 without health insurance), the Disability Lifeline, state parks funding, and programs for gifted children and juvenile offenders.

But Seattle Bubble readers are sharp cookies. The very first commenter zeroes in on the difference between the state’s past obligations and current spending: “Like most states and cities, the increase is from pensions (retired state employees living longer, with bigger pensions), and from health care costs for both current and retired employees and medicaid recipients outstripping inflation by a large margin. $2 billion removed from what’s left after these and other mandatory spending hits the remaining programs very hard.”

The fact is that only about half of the amount that The Tim has charted isn’t protected in some way–money specifically dedicated to some purpose that, to provide fiscal continuity, the state is not allowed to rethink now that revenue streams have dried up. People argue that the state has a spending problem, but if so, we need to change the verb tense: We have a spent problem.

The state has in the past agreed to pay for things that aren’t necessarily fixed costs (because they are tied to inflation, or because they fluctuate normally, like the number of people below the poverty line any given year). Even of the Near General Fund’s smaller amount, there is de facto protection: People rely on these services, and they become angry with legislators when they are taken away.

The truth is that, structurally, the state can’t afford not to grow its budget right now–certainly to keep pace with inflation, and above that to account for a doubling-down effect from the poor economy. The allocate-now-pay-later model leaves the state vulnerable to these downturns where revenue shrinks and the state’s social safety net burdens increase.

Gov. Gregoire has suggested a three-year, half-cent increase in the sales tax that exemplifies the old-school process. It addresses short-term needs without promising any reform, leaving the more cynical among the voting populace to ask themselves how many temporary taxes have, in fact, not been extended into permanent practice. Budget Schmudget, the blog of the Washington state budget and policy people, suggests that any sales tax increase be tied to economic indicators instead:

For example, if the sales tax were increased by one percentage point to 7.5 percent from 6.5 percent, the increase could phase down to 7.0 percent when the state unemployment rate falls to seven percent (it currently stands at nine percent). It could be set to phase out completely when unemployment falls to six percent.

Further, if cutting planned spending isn’t precisely cuts, they suggest at least not planning to give money away through tax subsidies that have little reason for existence. WSB&PC estimates that yearly the state holds a $6.5-billion giveaway in tax subsidies because the current rules require a two-thirds majority vote to change things. What’s wrong with a simple majority to end tax subsidies? asks Budget Schmudget, and it’s hard to argue with them.