Since the stepping down of co-founder Julie Tobiasson, Timothy Lynch has become sole artistic director of Seattle Dance Project, but there’s certainly been no step off in artistic energies — that’s in part due to new collaborations and new dancers with the troupe.

Project 5 (performed again this weekend at ACT, and if you have a $25 ACT Pass, make use of it) brings a guest appearance by Inverse Opera, premieres from choreographers Penny Hutchinson and Jason Ohlberg, and three new dancers: Iyun Harrison, Ezra Dickinson, and Gavin Larsen, who join Lynch, Michele Curtis, Alexandra Dickson, Betsy Cooper, and David Alewine.

Who am I to disagree with Sandra Kurtz, when she calls out the success of Hutchinson’s Liebe, Lust und Liede? So I won’t. Hutchinson is a founding member of the Mark Morris Dance Company, which is at this point in modern dance a lot like being a Knight of the Round Table. Using Brahms’ Liebeslieder waltzes — which in turn employ lyrical poetic outcries sung live by Inverse Opera — Hutchinson stages a formal dinner party where the tensions of love and attraction refuse to remain subtextual. (Regan McClellan’s set features a dining table upstage right that turns into a minimalist forest as passions grow wilder.)

The course of love never runs true, and Hutchinson lays out the dance on diagonals, frequently, using the greater distance to emphasize couples pulling apart or being drawn together. It’s great to see younger dancer Ezra Dickinson in this more formal context; Dickinson could easily pass for a cast member on The Big Bang Theory, but he’s properly starched up here, at least at first, before succumbing to the waltz’s passion. Project 5 is worth seeing twice for this dance alone, as Hutchinson’s dining room intrigues create endlesss opportunities for solos, duets, and ensembles (everyone shines, but I was struck by both David Alewine’s and Gavin Larsen’s performances).

Ohlberg’s Departure from 5th assembles a few of my favorite things: musings about the wisdom of experience, decrepitude, and music by Rufus Wainwright and Arvo Pärt. I’ve seen dancers narrate as they do their life’s work before, but it’s never stopped being affecting to me to hear about the personal struggle-decision to dance, perhaps because ballet dancers especially confront their own mortality earlier than most, as they find that the physical demands of professonal ballet surpass their abilities often in their thirties. (The Wainwright song? “Do I Disappoint You?”)

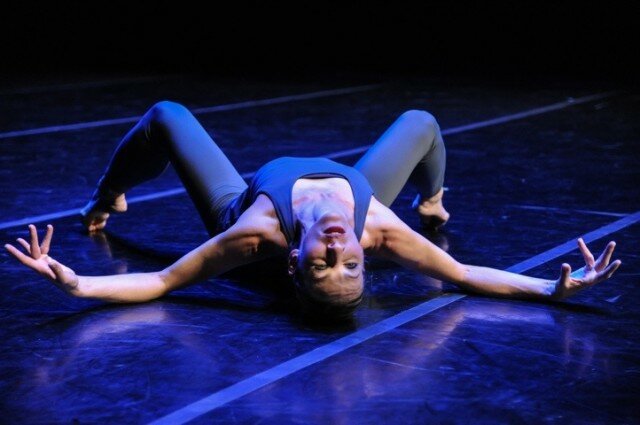

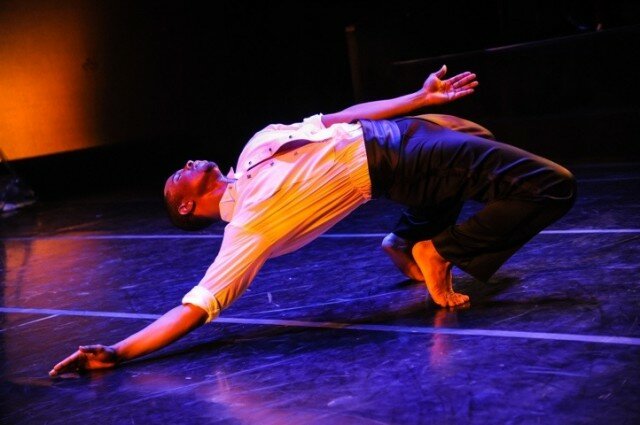

Here, interviews with the dancers are played as they perform, and so you hear about body images, perfectionism, technique, while the same dancer mutely gestures and moves about the stage. In the muscular, sculpted Iyun Harrison’s segment, danced with David Alewine, he talks about the tensions in looking like the heterosexist ballet “prince” as a gay man; Alexandra Dickson recalls the time her child’s legs were pronounced “sturdy.” Throughout, they are occasionally guided by gowned “Fates,” who near the end, pull a silvery sheet over the dancers like a high-thread-count scythe. It’s a wrenching visual, if you’re in the right (or wrong) space.

Also on the program are three previously performed favorites. First, Molissa Fenley’s Planes in Air, this time performed by Betsy Cooper and Alexandra Dickson. If you’re ever feeling blasé about dance, go see Betsy Cooper perform something, anything. In Planes, she finds a serenely exuberant place to go, supported by the way Fenley balances the ungainly and graceful of the winged body (each dancer holds a large white paper fan that is at times an extension of their arms, and at times partner in a spiritual pas de deux).

Edwaard Liang’s To Converse Too gets even better expression this time around than at its premiere. Set to Bach cello suites, it requires so much of the dancers in knotty little interludes, passages with unusual holds and exits, that they are nonetheless supposed to slip through as if buttered. The ensemble of Harrison, Lynch, Cooper, Curtis, and Dickinson pulled it off, mostly, with a refreshingly go-for-broke attitude that gave things a high-wire thrill.

In its own way, Kent Stowell’s B6 is also a high-wire act. It shows off “old pros” Lynch and Curtis in sizzling formal wear, and asks them to dance a pas de deux with the fierceness and panache of a tango. Lynch and Curtis are the kind of dancers who try never to let you see them sweat, so to speak, but I thought I could see the dancers straining a bit in the bravura displays of ballet strength in slow-motion en pointe pirouettes. It probably should come with an intermission both before and after, or, failing that, bionic tendons.