Mariano Pensotti’s El pasado es un animal grotesco (The past is a grotesque animal) has just a few more showings at On the Boards; it closes February 12 (tickets: $25). If you’re in your early 20s to early 40s, then this is a show that is especially freighted with personal import. No, you may not have turned 25 in Buenos Aires in 1999, but you will recognize so much of what you see here, as Pensotti charts the defining arcs of adulthood: Either you grow into yourself, or you grow away from yourself. Theatre doesn’t always deliver epiphany, but this one does, for anyone who’s ever struggled to unite passion and action.

On Tuesday–bear with me, I’m going someplace with this–I was taking a crosstown bus and musing that people might be just as happy riding Singing Buses, where you might get on the ’80s bus for an ’80s singalong. Would people even care where the bus went? I imagined an entire bus belting out “Forever Young” by Alphaville, and decided that no, they wouldn’t care.

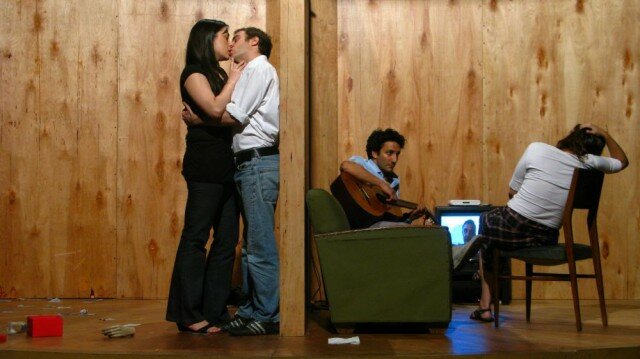

On Thursday, I was watching a slowly rotating Lazy Susan of a stage that, coincidentally, mirrored what the Space Needle restaurant nearby was doing as well. Onstage, Mario, Laura, Pablo, and Vicky were separately preparing themselves for the future as they imagined it (El futuro es un animal difícil de aprehender), and instead found themselves simply trying to cope, for the most part, as a turbulent decade spun by (over 60 short scenes in 110 minutes). At a karaoke party, they began to sing “Forever Young,” a song that tells you outright, “It’s hard to grow old without a cause.”

If you go, you might find yourself a little in awe of just Mariana Tirantte’s set, as it metronomically ticks by but also revolves, managing to be two kinds of time at once. It’s a kind of slide carousel with moving images, displaying the kind of “damaged” photos that Pensotti says he once collected from a photo lab, defects, mistakes.

A stagehand resets the stage partitions out of sight, so that your expectations of object permanence are often violated. Sometimes the set dressing makes a joke: a boar’s head is affixed to a wall (speaking of grotesque animals). Constantly shifting lighting from Matías Sendón (and Ricardo Sica) suggests times of day, the city and village, different countries, accompanied by Diego Vainer’s chameleonic soundtrack.

Pensotti’s text (largely narrated–an actor will describe the lives of another couple, hand the mic over, and embark upon acting out their own scene) is sometimes gorgeously metaphorical, in the surprising way of poetry, and sometimes helpfully direct.

“I want to be like a furnished room rented to foreigners,” Vicky (Pilar Gamboa) says, which is another way of describing the show, but which she means to describe her non-attachment. Laura (María Ines Sancerni) flees her small “nowhere” town for Paris, but returns to Buenos Aires, feeling like a battered train returning to the port for more cargo. “We are a mixture of what did and didn’t happen,” realizes someone. (All quotes from failing memory of the captioned work–it’s performed in Spanish.) If you’re familiar with Roberto Bolaño, you’ll feel right at home.

Mario (Santiago Gobernori), the would-be filmmaker, is missing just an “an” in his name to complete the resemblance to Pensotti, but Pablo (Javier Lorenzo), whose totem becomes a severed hand, has a more symbolic role to play, balanced by Lorenzo’s nuanced portrayal of Pablo’s obsessive fascination with severed body parts, which leads to several adventures, not least a terrific conversation with a morgue attendant.

I’m resisting sketching out the biographies in more detail because that is the story of the work, learning about these people as events befall them. 110 minutes leaves just 27 minutes per character, which is not a lot for ten years’ worth of episodes, but Pensotti feels that in watching the actors on “the wheel” for 100 minutes, you get a sense of how a decade ages people. With Bolaño, Pensotti is interested in how our lives become, for all intents and purposes, a fictional story we tell, edited, cropped, reshot or recast as needed. But Pensotti is as interested in what this process looks like from outside looking in, which suits theatre, I think, more than literature. That’s what grants us the epiphany here, that in life you’re only “faking it” if you don’t really mean it.