When the politicization of immigration becomes too much, there’s art to remind you that it’s an ancient, cross-generational human experience to seek new horizons, whether pushed or pulled, to feel both uprooted and at sea, to betray on old life with a new one, or betray a new life with the old.

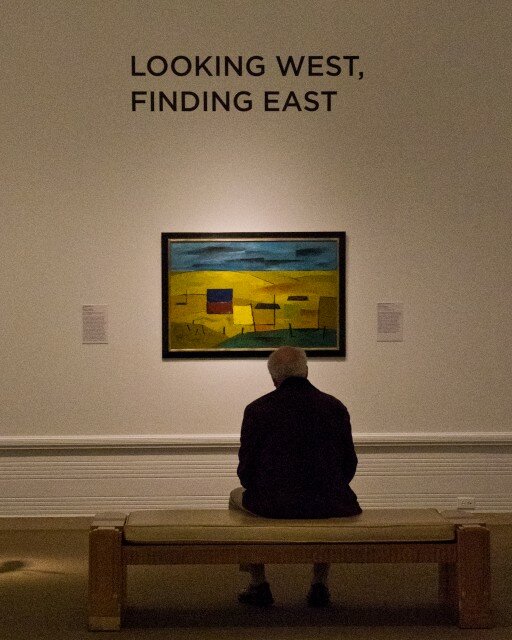

You have just a few days left to see the “Painting Seattle: Kamekichi Tokita and Kenjiro Nomura” exhibit at the Seattle Asian Art Museum. The exhibition closes February 19, and, accompanied by the adjacent exhibition, “Looking West, Finding East,” it offers visitors a potent vision, corrective and celebratory, of less-illuminated street corners in Seattle’s past. (I believe if you go to see SAM’s Gauguin exhibition, your ticket stub will also get you into SAAM for up to a week after.)

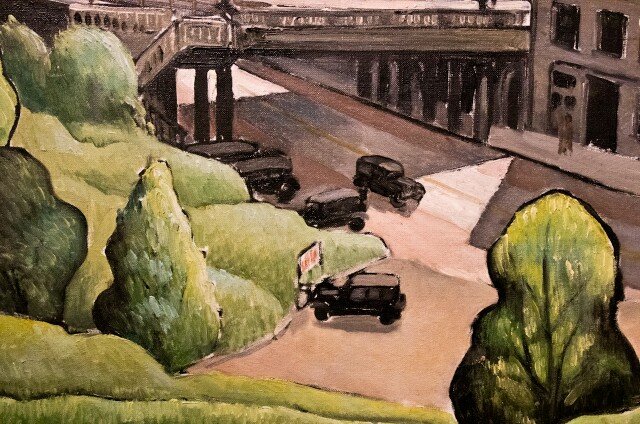

“Tokita and Nomura were the most prominent of a group of first-generation Japanese-American painters in the 1920s and ’30s in Seattle,” SAAM informs you. In a collection of some 22 paintings, you see how the two climbed Seattle’s hills around what’s now the International District to get views of what’s clearly home, and read how these respected painters were incarcerated, with their families, at Minidoka during WWII. Immigration is, clearly, a process.

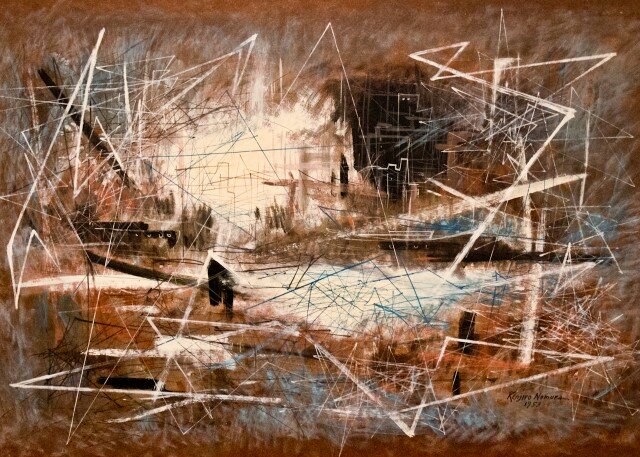

Only Nomura managed to live long enough to get his artist’s career back on track–his realist paintings (“Fourth Avenue”) are followed in the ’50s by abstractions from scenes (“Harbor”). So much is tangled up in the context of these paintings–’30s Seattle, anti-Japanese hysteria, the emergence of a Northwest artistic sensibility–that even this smaller collection lets you chew on what you’ve seen for days afterward.

While you’re there, stop in next door for the exhibition featuring Paul Horiuchi and George Tsutakawa–both were also caught up in the internments of WWII. Tsutakawa was, amazingly, drafted and served a tour of duty while his family’s business was confiscated. If you know Tsutakawa mainly from his fountains, his paintings and wood sculpture here will be like walking into a room you didn’t know existed. Horiuchi’s collages–torn, painted, dyed, onion-layered–express both the knitting together and unknitting of “reality,” scenes from nature that retain their presence and vitality while refusing to resolve into the familiar.

Skipping ahead to today, and to a different medium, author Krys Lee was just back in town, for a reading from her startlingly assured, engrossing collection of stories, Drifting House. Born in Seoul, Lee grew up in California and Washington (she thanks Heather McHugh in her acknowledgments), and lives, again, in Seoul. Her stories, too, hop continents, tracing out the migratory patterns between the U.S. and Korea, Korea and China, and also the conflicts and fluctuating fortunes that drive migrations.

Yet they are almost always highly personal narratives–these short stories don’t try to “stand for” or universalize. Mrs. Shin and her ex-husband (in “A Temporary Marriage”) had, or have, an explosive psychosexual bond that is particular to them. Sometimes, as in “At the Edge of the World,” cultural transactions double back on themselves. Two Korean immigrants in the U.S. have this exchange:

“I’m a shaman, widowed,” the woman said, each syllable separated, her head tipping higher with each word. “You should know that about us.”

“Jesus saved us,” his mother said emphatically. “I don’t do shamanism.”

Back in Korea, “The Goose Father” begins with an explanation of the term–“Korean men who had been drafted or volunteered as mercenary soldiers for the U.S. Army in Vietnam, and sent their salaries back to their family”–but then pulls in a real goose, a “beanstalk” of a young man named Wuseong, and an irruption of unmet needs. If, in contrast, “The Salaryman,” with its somehow schematic recounting of corporate expulsion comes to feel more like down-and-out reportage, but Lee follows that with the harrowing story of abandoned, starving children making a desperate run for China, a love triangle created by a girl “as long as a grain of brown rice.” I am not sure I remember the last time a short story collection kept me up, turning pages past midnight.

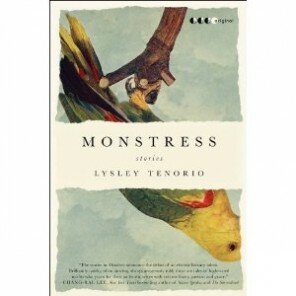

In Monstress, Lysley Tenorio ups the ante on idiosyncratic cultural entry points. The title story “stars” a never-made-it Filipino horror filmmaker and his disillusioned muse, who, in being “rediscovered” by a young, DIY Hollywood-ish filmmaker, are faced once again with the pursuit of fame, glamor, all those Hollywood exports. (Tenorio will in Seattle appear at the University Bookstore on February 23.) It’s a masterful opening to a masterful collection, colliding as it does so many expectations.

It was still early evening, and Gaz suggested we drive to the set. “MGM?” Checkers guessed. “Twentieth-Century Fox?”

“My mom’s basement in Pasadena,” Gaz answered.

It’s impossible, I’d think, not to laugh at that, but just lines later we also learn that “mom’s basement” still “would have been Checkers’ dream set. We’d had to make do with tin-roofed shacks and three-walled huts in shanty towns far beyond Manila, where we paid impoverished locals with cigarettes and sacks of rice to play our victims for a day.” Even this goofball Gaz character has more of a launching pad than Checkers and Reva ever did.

Before Lee and Tenorio, I’d been taking a break from fiction, particularly short stories, as they seemed to have mostly been written in the same mega-MFA factory, with short story authors positioned around the same model-subject, like a strangely compulsive life-drawing class. In short, not good material for illustrating the “social brain” claim that “those who immerse themselves in fictional worlds and characters may be more empathetic, open minded, and socially aware than those who do not.”

Tenorio’s dial, in this respect, goes up to the proverbial 11. In “The Brothers,” the death of one brother means the other confronts, viscerally, the sex change that finished driving a wedge between them.

Tenorio’s dial, in this respect, goes up to the proverbial 11. In “The Brothers,” the death of one brother means the other confronts, viscerally, the sex change that finished driving a wedge between them.

The story opens, deadpan: “My brother went on national TV to prove he was a woman,” but a little later Edmond says, “I looked over at Ma. It was like someone had hit her in the face.” In part, the story is about how Edmond’s half-hearted evasions of the things “all good Filipino Catholic families” do, without striking out on his own like his dead brother Eric, leave him in a limbo that’s robbing him of choices.

For Tenorio, place always has something affect-laden to say: “Yesterday, when I drove to ID the body, was the first time in years that I’d been to San Francisco,” says Edmond. To be here, not there, or to want to be there, not here, is often given a burning contingency. In “Felix Starro,” the grandson of a faith healer who’s cleaning up among expatriate Filipinos in San Francisco, feeling dragooned into an absurd, backward-looking life, makes heart-pounding plans to illegally buy his way into U.S. citizenship. Tenorio makes you feel the emotional dislocation of staring at your fake driver’s license for the first time.

Just when you think you’ve gotten Tenorio pegged, he transports you to a leper colony run by French nuns. In “Superassassin,” a Filipino-American kid finds in comic book hybrid-heroes a model for himself, and runs with that to unsettling teen-loner extremes. Or there’s the one about how a group of Filipino kids, in 1966, plan to rough up the touring Beatles in response to their insulting the theoretically-then-beloved Imelda Marcos.

In “Save the I Hotel,” Tenorio manages to make a short story feel epic, charting the decades-long, mostly-unspoken love between two Filipino bachelor tenants of San Francisco’s International Hotel, recounted as their eviction looms. Once, the hotel was where you stayed if you weren’t white, later becoming a cultural touchstone, but in 1977 you can be Filipino, and gay, anywhere, can’t you? Read it for the poetic compression of two lines like this:

Fortunado had never struck a person before, but there were times in his life he wondered what it might be like, and now he knew: the force of everything you are in a single gesture at a single moment; the hope that it will be enough and the fear that it won’t. No different than a kiss.