In I Am My Own Wife, playing at the Seattle Rep through March 4, you are not, actually, guessing whether Charlotte von Mahlsdorf is a man or not. The German transvestite born Lothar Berfelde was not hung up on passing. The alternate translation of the title, what she said she told her mother in response to a question about marrying, is “I am my own woman,” and in Charlotte’s case, all that was needed was a dress and pearls.

Directed by Jerry Manning, and starring Nick Garrison as Charlotte, this production of Doug Wright’s play keeps you guessing about something else entirely. Wright, after all, wrote the play because he was thunderstruck that someone who lived openly as a transvestite managed to survive under both the Third Reich and Communist rule. But as becomes apparent, compromises were made.

At a hundred and forty minutes, with one intermission, I Am My Own Wife is lengthy by solo-actor standards, and is essentially about a number of conversations held with a 65-year-old, self-styled museum curator, so you have to make allowances, and sit back and relax as Charlotte tells her story in her own time, complete with digressions and evasions, instructing you in the history of the Edison Gramophone and the antique furniture in her Gründerzeit Museum.

Wright’s play seems to take for granted that everyone, at the outset, will be as fascinated with Charlotte as he, and proceeds chronologically, so it’s a while before you start hearing about life in Nazi Germany, and subsequently the infamous East German Stasi police. Additionally, in putting himself into the story, he’s doubled the responsibility of the solo performer, who has to make us both care about Charlotte’s history and Wright’s predicament, in trying to tell it.

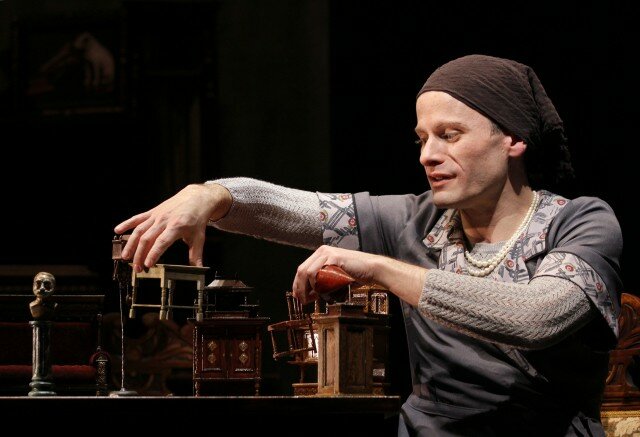

Luckily, the Rep is drawing upon the substantial talents of Nick Garrison, who plays some 30 different characters in the course of a performance, with almost nothing in the way of the “breather” of costume changes. (Costume designer Erik Andor contrasts Charlotte’s gray dress only with a prison uniform.) Garrison’s Charlotte is almost too real, in that she often, coyly, refuses to get on with the story. Garrison’s voicing is nothing short of marvelous, carrying both a German accent infused with an accent from Charlotte’s English lessons.

Supporting Garrison is the work of the creative team: Jennifer Zeyl’s conceptually-apt set, with its startling reveals; the shifting shadows from lighting designer Robert Aguilar; and the stately music of Charlotte’s unstaid life, supplied in gramophonic glory by Robertson Witmer.

Manning and Garrison have aimed for nuance, letting a layer of paint dry before another is applied, and if at points it feels slow going, the cumulative impact is palpable, as you come to know Charlotte, and the choices she made–or didn’t. The ambivalence about what happened comes to feel like the grain of sand in an oyster’s shell, and the result, of course, you can see on Charlotte.