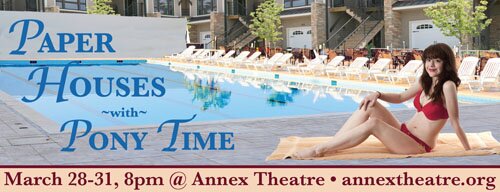

Perhaps you heard about this production of Paper Houses (at the Annex Theatre March 28-31; tickets: $20) from the promotional spots on KEXP, a reportedly reliable source for taste-making in music. Indeed, the music is great.

Seattle duo Pony Time is playing an awesome evening of hard rock at the Annex Theatre this weekend. There will be dancing. Stacy Peck will loom at you over her drum kit and make sure of it. Also, Luke Beetham’s guitars are things of beauty and deserve concentrated admiration while his fey vocals and agile finger work make for hipster happiness. However their sets are interspersed with theatrical scenes, and the less said about those scenes the better.

It might be preferable just to talk about the actors. Correy Harris stands out from the get-go as a fine actor foundering in text and direction that work to hide his talents. The intimations of character and relationship suggested by Harris’s presence in the role of Nick are also evident in the work of Patricia Bonnell as Iris and Anna Giles, as Abby.

Robert Harkins has perhaps the most challenging work in this play in the role of Stanley, a man suffering from dementia, though he is freed from the need to make sense of his lines. David Cravens-O’Farrell, connects with the audience sporadically in the central role of James. His accent is similarly sporadic but let’s chalk that up to his late addition to the cast.

The only role more thankless than that of Stanley may be this play’s villain, Bartman (Jay Hill), and not only because he shares the name of a dubious novelty dance from the early years of The Simpsons. In lieu of character, Bartman is a collection of negative stereotypes of current American conservatism. Hill appeared to be unsure of his lines, though his were not the only scenes in which vast pauses separated one character’s line from the next.

In the aim of promoting better theatre a few observations of the play are in order: Curtis Lee Fulton has tried to pack way too many themes into this narrative. These themes do not add up to actual content or articulated ideas. There are so many unmoored references that no time remains for establishing relationships through interactions; instead the relationships are simply named.

The most prominent flaw in this play (aside from the implausible situations, characters and relationships—such as they are) is that it is set on the catwalk of a billboard. This places large demands on the set, the actors, and ultimately the audience. The set fails to suggest anything more than a billboard that might as well be at ground level; the actors are inconsistent at best in the ludicrous shimmying that indicates the platform’s height. The audience is left to try to justify all that happens on this strangely deep catwalk–including the arrival of the band set-up on wagons for a rehearsal, and later performances, that ostensibly take place on the catwalk. Possibly the wagons are actually floating several feet in front of the catwalk and at a deadly height off the ground.

That said, Fulton is to be commended for taking some risks and experimenting with the integration of a rock band with a stage play. One hopes he would have learned from more successful forays in this field such as The Dresden Dolls’ production of A Clockwork Orange or The Negro Problem’s Passing Strange.

While Paper Houses is a failed experiment there may be further opportunities for the material. Verisimilitude seems beyond the reach of anything associated with this project but going bigger and more artificial could make for a dynamic performance. Let the angst-laden screeds stand alone, screaming down from a billboard high above a dance floor. Spotlight the senile and the socially diseased, do everything this play does only bigger and stagier. Dispense with narrative and plot, even give us a dunk-tank clown like poor Bartman and, please, have the band play more!