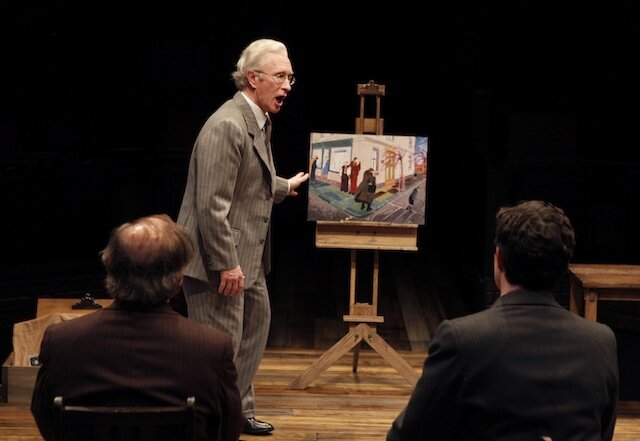

Earlier this season Seattle Rep brought us a play in which a pair of artists talked about art theory, commerce, society and the relationship between the three. This month ACT presents a play in which the characters discuss art theory, commerce, society, and the relationship between the three. However where Seattle Rep’s Red did little more than tell us about art (and a bit on its relationship to commerce), ACT’s The Pitmen Painters does more showing. In this, the script is a more successful work of drama. In ACT’s production (through May 20; tickets) it is well played with as much in the way of easy laughs as meaty intellectual content.

Though the dialogue mostly focuses on the art, The Pitmen Painters is less about the art than it is about society: specifically, the rise of socialist England. The play includes the major players of both the artistic and societal dynamics of the time. These include an artist, an artist/academic, a patron, and five eponymous artist-miners, known as The Ashington Group. The scenes take us from 1934 to 1948, the period in which these real-life artist-miners rose to prominence, and England pivoted from capitalist empire to socialist democracy. We see the miners struggle with the vast changes of the period on the personal level.

While the reverberations of the Great War remain strong enough to incite discord and even violence in early scenes, whispers of the coming WWII quickly grow to shouts. Yet for much of the play, the big stage of world events plays out in almost incidental details that make Downton Abbey feel forced and didactic by comparison. The Blitz begins, but life goes on–with occasional interruptions by air raids and casualty reports.

The politics that dominate the play are not those of fascism versus freedom, but of class and the dignity of work. The miners remain consistently proud of their work, but they are changed by their experiences as artists and by the societal changes those experiences represent. Through these changes they develop higher standards of living and a greater sense of ownership of their work. [For a modern-day take on this dynamic, don’t miss Brazilian artist Vik Muniz in the documentary Waste Land.–ed.]

From the get-go, the miners, who at first shy from the alien world of arts and high culture, bridle at the first hint of exploitation or condescension. As they grow confident in their own opinions and the value of their individual artistic visions they also become politically empowered. The play ends with a utopian vision of socialist England—crushed by the footnote of its Thatcher/Blair era deconstruction. There is some premonition of that footnote in that the toffs never entirely escape the myopia of their privilege. Each has a recognition scene in which they come to see their sins to varying degrees, but a post-class unity never comes to be.

Clearly this is a play full of big ideas and it manages those ideas well. The plot enacts the intellectual content of the dialogue, but there is little in the way of character. This might not be such a problem were the production less realistic. Though episodic, the structure is fairly standard-issue. This often feels at odds with the intellectual content and does not support the weak characterizations. A more abstract production, or perhaps one with actors who are overtly amateur, might make for a more full and powerful experience. Alternatively, more fully realized characters might justify the largely realistic portrayal.

The actors do work hard to build character from the thin, almost symbolic outlines of Lee Hall’s dialogue, but only three characters come to dimensional life. These include the central artist-miner Oliver Kilbourn (Jason Marr), the artist-academic Robert Lyon (Frank Lawler), and the merchant-noble and arts patron Helen Sutherland (Morgan Rowe).

Hall seems to acknowledge the weaknesses of the other characters through the socialist dentist, Harry Wilson (R. Hamilton Wright). Wilson begins the play focused on symbols and the need for art to say or do something for society. The predilections of Jimmy Floyd (Joseph P. McCarthy), an illiterate among high-cultural innocents who just wants things to be true and attractive, are given voice as well. He also gets most of the laughs. Ultimately it’s the voice of George Brown (Charles Leggett), the by-the-numbers union official that dominates this production. The Pitmen Painters may present a quiet portrayal of revolution, but there is nothing revolutionary about the production. It is nicely presented, funny, smart, and a touch bittersweet.