Director Harold Clurman has been quoted as saying that he made comedies so when people opened their mouths to laugh he could pour the truth in. In Jesus Hopped the A Train Stephen Adly Guirgis isn’t interested in force-feeding us answers but in asking hard questions we would normally duck. However Guirgis asks these questions by shocking methods and the shock is so fascinating that we can’t help but stare. There are also more than a couple laughs to help the medicine go down.

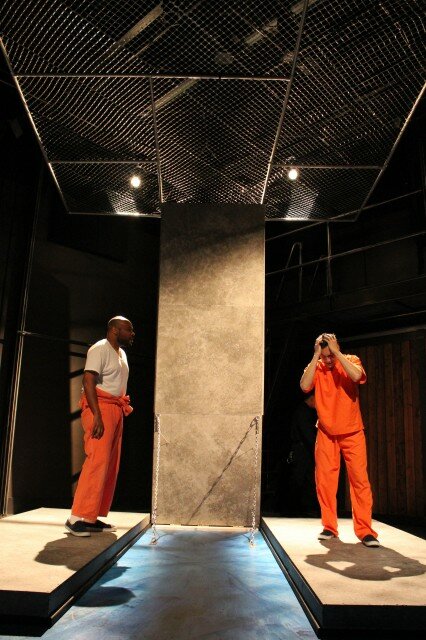

This Azeotrope production (at ACT through June 30; tickets: $25) is set largely within Riker’s Island prison, in the East River just off Manhattan. Over the course a few brief, mostly two person scenes and monologues, a story unfolds of a young man coming to terms with guilt and redemption.

Unable to save his best friend from a cult, Angel Cruz (Richard Nguyen Sloniker) shoots the cult leader and is arrested and tried. His lawyer, Mary Jane Hanharan (Angela Dimarco), fights through Angel’s resistance in a personal crusade for absolution through defense of a noble act. Her job is complicated by the involvement of Lucius Jenkins (Dumi) a charismatic serial killer who inspires and confronts Angel, and the audience, through the ardor of his personal redemption. The competition between Mary Jane and Lucius to save Angel by legal or spiritual means forms the story’s central conflict and few escape the battle unscathed.

Guirgis does not ask us to forgive people we find reprehensible. Rather he assumes that we will forgive, that we will empathize. The jury, we are told, wants to redeem the accused, wants to believe he is innocent. Then Guirgis asks us, and the characters of this story, to deal with the implications of forgiveness, which can be devastating to those who seek absolution for themselves. The truth, of course, is far more complicated than simple guilt or innocence, and the truth is not always right. Where does honor come into justice? How do we respond to the desire for vengeance?

The cast is strong overall. Patrick Allcorn and Ray Tagavilla do fine work as contrasting prison guards. Each delivers a monologue in a conversational style that is true to his character. Angela Dimarco is far more stilted in her monologues, which feel less like conversation than an actor delivering monologues. She does the tough-lawyer act well but her collapse is guarded and we struggle to care for her difficult but socially acceptable character. Dumi is a force of nature most terrifying in his least forceful moments. A casual admission from his character turns the entire play on its head. It’s a delicate and vital moment that Dumi nails effortlessly.

This play could be done on a bare stage—a table and chairs help, but little more is really necessary. It can be done in the most intimate of settings, as it is here, but it has more than enough power to hold a much larger stage with a much larger house. This production feels simultaneously sprawling and miniscule. The set is a little brilliant. It spills off the stage, using the existing structure of the space to excellent effect, and gives us only the most important pieces of this physical world. The actors give a hand with precise movements that show the prison bars when we need to see them. The biggest set change is breathtaking, and while it’s not strictly necessary it doesn’t distract either.

The costumes also do their work efficiently—though some of the uniforms seem oddly lacking in starch. Lighting is more than simply workmanlike but lacks finesse in providing emotional support. Frequently the timing feels off, the areas too tight, or the effect distractingly large, but this is nitpicking in comparison with the sound.

While Christian “Lil Kriz” Beeber’s original music is almost reason enough to see this show on its own Jay Weinland’s sound design is excessive and frequently wrong. When Lucius notes a passing seagull we hear a crow cawing as it takes flight. The subway sound effects are almost diffuse enough to be forgiven but New York City subways are very distinctive sounding and worth getting right. Here too the effects miss the emotional timing and this consistency in errors suggests that culpability ultimately lies with director Desdemona Chiang. The worst aspect of the design offences may be that the play and this production don’t need the emotional support. We feel the tension from the actors’ words; we don’t need anything more than that.