“Pioneers like Portland, Seattle and San Francisco have become so good at waste diversion,” writes the New York Times, “that it is becoming harder to get much better.” End of June, Seattle Public Utilities announced that for the eighth straight year, Seattle’s recycling rate had increased. Overall, more than 55 percent of solid waste is recycled, up almost two percent. But for single-family homes, the rate is more than 70 percent, a fanaticism lightheartedly chronicled in PEMCO’s “Obsessive Compulsive Recycler” ad.

July 1, a plastic bag ban went into effect that, SPU estimates, SPU estimates, will result in 16 fewer shipping containers sent to the landfill each year, besides cutting down substantially on plastic bags blowing in the wind. Grocery store customers now must either bring or buy a reusable bag, which usually retail for about a dollar, or can buy a paper bag for five cents (“must be a minimum of 40 percent post-consumer recycled fiber and the fiber content must be marked on the outside”).

The disheartening reward for this outstanding civic behavior is that public utility rates are expected to climb steadily in the future. (Reborn Publicola has details on electricity rates spiking an average of almost five percent each year for six years, for a total of 30 percent by 2018.) Drainage, sewer, and solid waste services would go up almost four percent each year for the next three years, so twelve percent, cumulatively. (SPU announced the planned increases two days after celebrating the higher recycling rates.)

“Key drivers” of the increase, says SPU, are “decreased revenues resulting from the economic downturn, as well as higher taxes and inflation,” which interestingly are key drivers affecting utility customers, as well. Staff have already been laid off, and SPU is currently trying out a six-month pilot program on 800 households, testing every-other-week trash collection. If adopted, this might result in $6 million in savings annually–the question is, can Seattle stuff two weeks’s worth of garbage, and how bad will it smell?

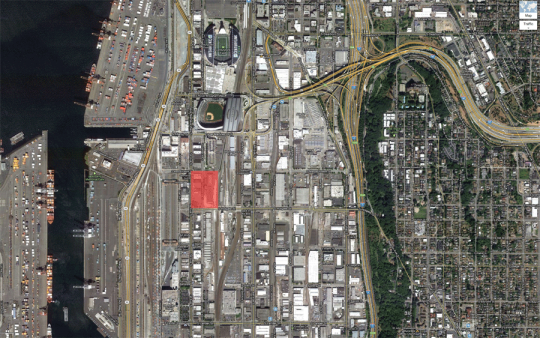

But SPU has also been investing in new infrastructure: a $50-million transfer station upgrade in South Park, due to open officially this summer, and a $52-million upgrade to the Wallingford transfer station, with design to begin this summer.

View Larger Map

Part of the reason for the upgrades to the transfer stations, as the Times mentioned, is that waste sorting takes up more space than simply dumping everything into a shipping container. But, William Yardley writes, SPU didn’t stop there in its improvements to the South Park facility:

The building puts a bright face on what some people might otherwise deem a dirty industrial endeavor. Old street signs decorate its entrance, a former drawbridge is a sculpture out front, the landscaping is irrigated with captured rainwater, and waste is misted to keep odors down. Windows allow abundant natural light.

Another substantial cost, with nothing to do with recycling, is SPU’s federal-and-state-regulator-prodded efforts to halt recurring overflows of raw sewage and stormwater into Seattle lakes, rivers, and streams. SPU wants to set aside $500 million to pay for things like “retrofits, green infrastructure, and large underground storage tanks.”