Seattle Opera’s Fidelio is a must-see production, and there are only four more chances (it closes Saturday, October 27). Not only are the performers superbly cast and directed as both singers and actors, but lighting and musical direction are also stellar. The whole adds up to a remarkable, moving production which leaves the opera-goer shaken and stirred.

The choice of using Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3, rather than the much shorter Fidelio overture, sets the stage for this production with the juxtaposition of noble music and bleak set. We are faced with a tall mesh fence topped with barbed wire, while at the side are scaffolding towers with searchlights on top. It’s night, and as the overture continues, in a performance under the conducting of Asher Fisch as beautiful, meaningful, and smooth as I’ve ever heard it, a light sweeps slowly along the fence and back, over and over. It’s chilling.

The lingering sense of this production is of characterization. Stage director Chris Alexander has encouraged each of the major performers to plumb the depths of their characters, so we see and hear complex people making complex decisions pushed by forces not necessarily under their control.

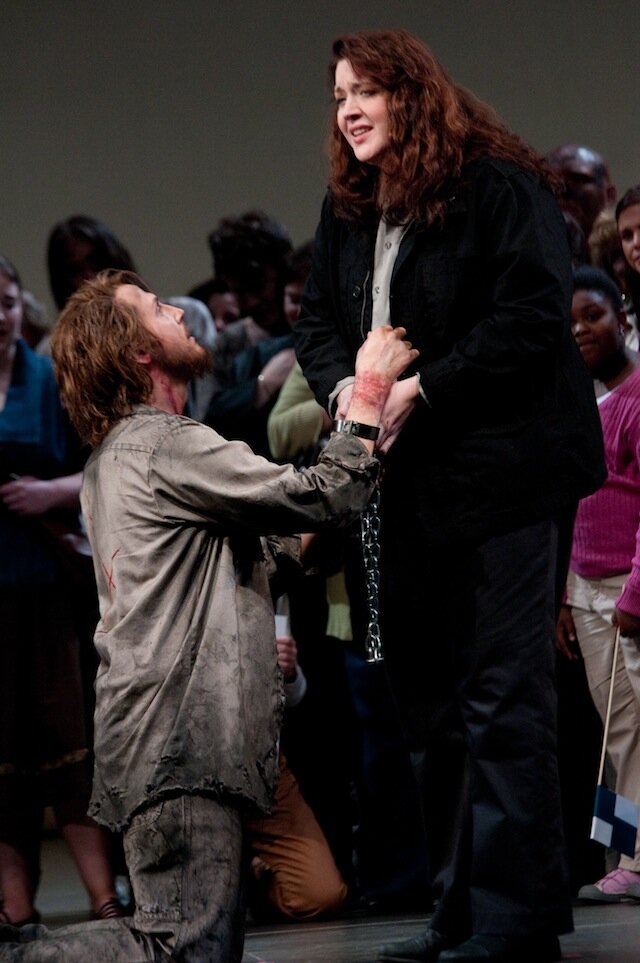

Leonore, the heroine (in male guise as the jailer’s assistant, Fidelio), is sung in all but one performance by the great German soprano Christiane Libor. In her Seattle debut Saturday night, we saw her trying to walk the fine line between winning the jailer’s approval and thus the chance to get into the worst depths of the jail where she hopes to find her husband, Florestan; and not over-encouraging the advances of the jailer’s daughter, Marzelline, who is convinced she is in love with him. At the same time Leonore is desperately frightened lest she not find her husband, or find him too late. With a big but agile voice, Libor was eloquent in every musical line and every gesture.

For Sunday’s performance only, Leonore was sung by recent Seattle Opera Young Artist Marcy Stonikas, who also undertook the title role in Turandot last August. Stonikas’ voice is a tad smaller than Libor’s but she also has the big-voiced agility to encompass this musically difficult role with apparent ease. The experienced Libor and the newcomer Stonikas worked on the singing and characterization together, and it showed in a highly satisfactory role debut here for Stonikas.

It’s typical of general director Speight Jenkins to nurture young artists, and he is adept at seeing potential. In this production there were no fewer than four from the Seattle Opera Young Artists program, including two prisoners and also soprano Anya Matanovič as an artless Marzelline, excellently portrayed.

As Florestan, Clifton Forbis made the most of his vocally difficult role with his fine big tenor, accomplishing it with ease and acting with conviction, though it is hard for a well-padded man to appear starving. Forbis had expected to sing all six performances, but on Thursday his understudy gave such a compelling performance in the dress rehearsal that Jenkins decided he should have the opportunity to sing the role Sunday afternoon.

Ric Furman is another Young Artists Program graduate, this time with Cincinnati Opera, and Sunday appears to have been his first big role with a national opera company. Another big voice of beautiful timbre, he also had no difficulty with Florestan’s vocal part, and his acting was the more convincing because, being lanky, he had an easier time looking starved.

With bass Arthur Woodley singing Rocco the jailer, Rocco came across as a decent man, concerned to keep his job but browbeaten and bullied by the jail warden, Don Pizarro; happy to see his daughter marry Fidelio; but nervous about ever stepping over the line in his duties, drinking on the sly to cope. Woodley gave a masterly performance, his ambivalence always there but never overdone.

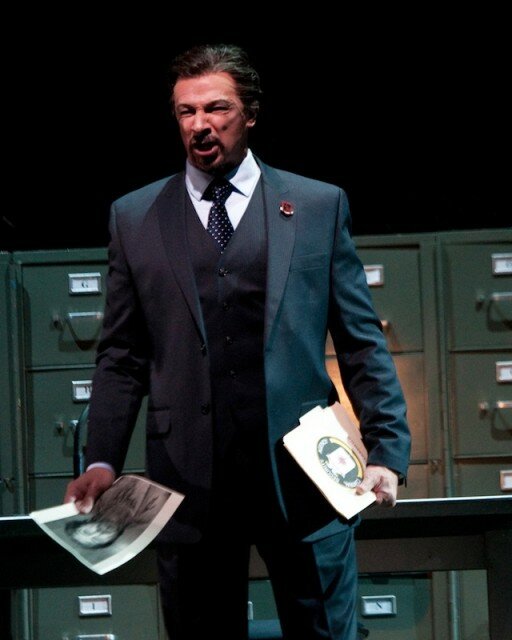

Bass-baritone Greer Grimsley took on the villain of the piece, Pizarro. In his hands, Pizarro came across as a ruthless, violent man, his behavior with Rocco threatening and unpredictable, with fear for his precarious climb to power and rage at his perceived enemies never far from the surface. Contrasted with the rich warm bass of Woodley, Grimsley made his equally deep voice hard, stentorian, dictatorial.

The last character to appear, the new government minister who releases all the prisoners and has Pizarro arrested, was Kevin Short as Don Fernando. He also has a rich, warm, powerful bass-baritone to match all the other voices, while tenor John Tessier does well as Marcelline’s would-be swain Jaquino.

The prisoners’ two big choruses brought a lump to the throat, first so despairing but with joy at seeing the sky, and second with unbelieving ecstasy at freedom as families searched frantically among them to find husbands, sons or lovers.

Alexander’s direction brought out all this detail and much more, but never laid it on with a heavy hand. The brutality of the jail was made obvious with a few incidents, while Beethoven’s high-minded music sharpened the contrast. Duane Schuler’s lighting throughout enhanced the action, while Fisch’s musical direction made it all the more compelling. At the start of the second act, both Saturday and Sunday, Fisch received a prolonged ovation, on Saturday with bravos as well.