After about an hour of Bach’s preludes and fugues last night, pianist András Schiff paused for just a few seconds, then launched into No. 12, and a familiar stair-stepping of notes for anyone who’s ever heard Jem‘s most popular single, “They,” from 2005. (She sampled the Swingle Singers‘ 1963 adaptation, or so Wikipedia tells me.) The internet has been amusing itself by tracking down Bach guest appearances, and if nothing else the list proves that Bach can jump out at you anywhere. More to the point, it demonstrates the sympatico nature of fugues and sampled repetition.

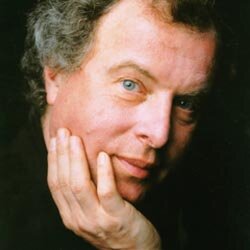

According to Philippa Kiraly, writing in the Seattle Times, and her watch, Schiff played 70 minutes, took an intermission, and played another 80 minutes. He played the whole of Book II of The Well-Tempered Clavier from memory (sparing a page-turner from fainting of exhaustion or claiming RSI). That’s not astounding in Schiff’s case–he loves Bach, and is one of the world’s most respected performers of Bach’s music. (His Bach Project tour supports his recording of The Well-Tempered Clavier, Books I & II. There’s even a Well-Tempered Tweets feed.)

The reason I mention the length of the concert is that the way Bach flows from Schiff’s fingertips erases time. For the majority of Benaroya Hall Monday night, an hour and ten minutes of Bach was just an appetizer. Another hour and twenty minutes, now that’s more like it. In fact, they had Schiff out for repeated bows until he played an encore, “the Prelude and Fugue in C major, from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I,” adds Kiraly, who knows her Bach better than I.

The reason I mention the length of the concert is that the way Bach flows from Schiff’s fingertips erases time. For the majority of Benaroya Hall Monday night, an hour and ten minutes of Bach was just an appetizer. Another hour and twenty minutes, now that’s more like it. In fact, they had Schiff out for repeated bows until he played an encore, “the Prelude and Fugue in C major, from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I,” adds Kiraly, who knows her Bach better than I.

Listening to Schiff’s Bach is “like looking down into a bubbling stream, seeing all the crisscrossing rivulets–and the tumbling stones at the bottom,” says Richard Scheinin in the Mercury News. People talk about the emotion “in” Bach, which can sound odd when you think of the formalist constraints, but the music has a way of creating a counterpart, emotional landscape in the attentive listener. The clots of notes seem to knead loose little griefs or joys.

It’s bit hard to credit your eyes: You can watch Schiff, sitting zazen on his bench, a slight rhythmic nod to his head at certain passages, his arms relaxed, and never quite believe that his fingers are producing that torrent of notes. There seems the barest of force in his fingertips, as if his fingers are moving too fast for your eyes and you’re seeing every other key strike. (Very early on there were a few microsecond hitches that I wondered were for interpretive effect, but then they disappeared.)

It is true you can buy the recording, and why not, but you are unlikely to want to tell the story of the last night you let your iPod take the Clavier to the end of the line. In Benaroya, people were strangling on their coughs, trying to keep them in, not entirely out of politeness, I suspect, but because they didn’t want to miss a note.