With a 7.7 earthquake to the north at Haida Gwaii and Hurricane Sandy working over the East Coast, it feels like a good time to have Arne (@nwquakes) talk with emergency management expert Carol Dunn (@caroldn) about a higher-risk group: renters.

What are some things renters can do to help protect themselves?

The impact from disasters can be reduced when communities work together in advance to identify and reduce risks, to gather supplies, and to train to work as a team to respond to disasters–but this can be harder to achieve in areas with a high number of people who are renting. In King County, there are a number of cities where more than half the people rent and not own. Because renting can lead to more frequent moves within the community, individuals may not feel vested in the neighborhood or community. And, local preparedness training efforts can be hampered by residential turnaround.

But as a renter, you can provide guidance to other residents—help teach them how to safely conduct light search and rescue/first aid, and do welfare checks after a disaster. Work with your management company or property owner to see if they will be willing to provide emergency information to new tenants: perhaps a simple handout with contacts listed, info on tools and other equipment stored inside the building and how to access them, emergency exits, nearby emergency shelters and medical aid, etc.

Reach out and talk to your neighbors. Share your telephone numbers, and a number of a contact who lives out of the area. If you are away from your home and a disaster strikes, you will be relieved that you have someone you can talk to who might be able to tell you the status of your location. This is particularly true if you are the caregiver for someone (person or animal) who can’t communicate on their own. Out-of-area contacts are useful after disasters if no one can return to their original location, and in the period immediately after a disaster, when local phone lines are more likely to be jammed than long distance lines.

Rental insurance is really important. The owner of the property will have insurance that covers their building, but not the things you have inside the building. Also, a lot of people don’t realize that property owners aren’t required to rehouse and repair units damaged by a natural disaster. I’ve seen situations where property owners simply declare the buildings too damaged to be used, so, since disasters are considered Acts of God, the residents are not allowed back, and not given any assistance by the property managers to find new housing.

Mind you, this can also be an advantage in a post-disaster period: if your unit becomes inhabitable your lease is no longer valid, providing flexibility that allows you to relocate to an area that isn’t damaged. This can make recovery faster and easier. But, studies have shown that being forced to relocate with no advance warning is emotionally hard no matter what the circumstances, so be sure to take advantage of opportunities to talk with counselors who have specific experience working with people who have undergone disaster related trauma.

Frequently multi-housing units are electric only—heating, stove, refrigeration. This makes a power outage in extreme weather hit harder. Have backup heating, lighting that doesn’t require any sort of flame or burning anything (candles, camp stoves, etc.), backup food that doesn’t require heat. Fire and carbon monoxide poisonings frequently happen in the period after the cause of the disaster have passed. Multi-housing units may depend on electric pumps working for water to reach apartments—and may not have water heaters in individual units. This makes water a more serious problem.

Do you have other advice?

The very nature of multi-family units mean that you are living with others nearby, so the mistakes of others can impact your life. Be sure to have a carbon monoxide detector with a battery backup. If a nearby family uses charcoal or a generator inside, creating odorless, invisible, dangerous gas, you will be warned that the gas is in the air. Don’t assume that your smoke detectors work: Test them yourself.

Often there are rules on whether you can bolt furniture to your apartment walls. If the rules say you can’t, work with other residents to try to influence the owners of the property to change the rules. In the meantime, consider the location of furniture that might fall down in an earthquake. If you can’t brace your furniture to the wall, you should at least move it away from places where it might tip over and hit someone (i.e., near beds, chairs, and couches). And you don’t want furniture where it can fall and block doorways and hallways and any other exits.

Since we live in an area with flooding, landslides and earthquakes, it is important to spend time evaluating whether the place you want to live is at risk from each of these hazards. Your ability to make it through a large disaster will largely depend on how well the building you’re in holds up to the disaster. People living in buildings that are not in flood zones have radically different experiences during a flood than people living in buildings in flood zones.

Likewise, people living in buildings that were built to handle earthquakes have radically better chances of recovering quickly from an earthquake than people living in buildings that can’t withstand shaking. Take the time to evaluate your building and its risk of being damaged in a disaster. A benefit to renting is that if you learn you’re in a risky building, it’s easier to move to a safer building pretty quickly.

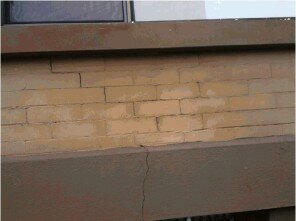

Do not make the mistake of thinking that landlords can’t offer units for rent that are in bad earthquake buildings, or located in an area known to flood. Local laws state that only new buildings, or buildings that have undergone major structural renovations, need to meet current earthquake codes. We have literally hundreds, if not thousands, of rental units in the Puget Sound region (See this Capitol Hill map–ed.) that are in buildings made with materials and techniques that cannot handle earthquakes well, or are in areas that flood.

Since there is no law requiring property owners to make such buildings safe for earthquakes and flooding, it is up to us as individuals to make sure we don’t live in them. Learn how to recognize buildings that don’t handle shaking well, or are in flood zones.

LINKS:

- How to Secure Your Building

- Three Days, Three Ways (pdf)

- King County Hazard Maps & Data