Each program this fall conducted by Seattle Symphony’s still-new music director Ludovic Morlot has come with a fresh outlook and, often, surprises. Over and over again, the different works on the program have been shown to have connections which may not have been particularly understood before the performance, and when they are, a shaft of enlightenment comes along also.

His musical direction of the orchestra is nuanced and well thought out, and the orchestra is responding with fine performances and, unusual for musicians (who often regard any — and certainly their own — conductor as having clay feet), enthusiastic approval shown by their applause as he comes on stage.

Last Thursday’s program was a case in point. The Berg violin concerto and Mahler’s 4th Symphony would seem to be a perfectly okay grouping, but it wasn’t until the performance itself that it became clear that the thread which linked them was the consideration of death in childhood.

Berg’s concerto, requested by violinist Louis Krasner, ended up with the composer’s distress and sorrow at the death of young Manon Gropius (daughter of Walter Gropius and Alma Mahler) emerging transformed into a memorial work dedicated to her. Mahler’s symphony, from 35 years earlier, channels the composer’s interest in a poem from Das Knaben Wunderhorn, where the words of children who have died describe what it is like in Heaven.

The Berg work is not an easy one for a listener not deeply familiar with it, unless it is presented by a violinist and conductor who have internalized it and can put its meaning across.

German violinist Veronika Eberle, 24, seems amazingly young to have done so, but the gentle tenderness of her performance, its heartfelt singing sometimes rising to anguish even in 12-tone serialism, gave humanity to the concerto. Fiercely difficult passages caused her no problems at all. The orchestration is often spare, but Morlot had the musicians on the same wavelength as Eberle, and the whole was a triumph, as was obvious in vociferous applause from the orchestra and also from the audience.

The Mahler appears at first thought to be totally different, from the end of a lush romantic era. The orchestra is large, the orchestration full, and all of the symphony hinges on the last movement, where a singer joins in with the words of “Das himmlische Leben” (“Life in Heaven”).

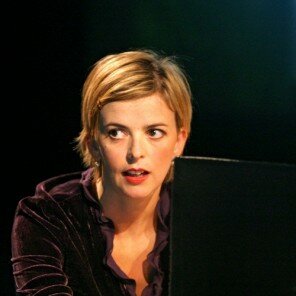

Often this is sung by a mezzo-soprano with a voice matching Mahler in its deep romanticism. Morlot chose instead a soprano, France’s Donatienne Michel-Dansac, with a chameleon voice which could sound as pure, ethereal and vibrato–free as a boy’s, yet deepen and sound warm in other sections. There was some sacrifice of volume in her lowest register against such a large orchestra, but she was able to project and could still be heard, though softly at those points in the score.

Clothing normally has little place in a music review, but Michel-Dansac’s appearance at the side of the stage toward the end of the third movement, standing motionless, with her smooth pale blond hair and a shoulders-to-floor palest pink pleated dress made one wonder if she had wings on the back.

Morlot guided the orchestra though this big work, with its many instrumental solos, deftly and with a sense of celestial lightness and often joy even in the loudest parts. Concertmaster Alexander Velinzon particularly deserves kudos for his playing in frequent solos.