When King County Metro looks forward to 2014, the agency sees thunderclouds. But the looming budget crisis isn’t one of the agency’s making. It stems from a 2009 agreement on the Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement project, approved by ex-Governor Gregoire, ex-King County Executive Sims, and ex-Mayor Nickels.

Once construction began, Washington State’s Department of Transportation would pay King County Metro $32 million to aid with traffic congestion: “for more buses and more service hours so people could get out of their cars, as Highway 99 construction narrowed traffic to two lanes each direction,” as Mike Lindblom reports in the Seattle Times.

But that funding is due to end in June 2014 — the same year as a temporary $20 car-tab fee, instituted to prevent Metro service cuts, expires. The plan was to return Metro to firmer financial footing with a permanent car-tab fee but none of the signatories had the power to do that. Only the State Legislature could, and so far, they haven’t.

What Gregoire, Sims, and Nickels could do was present everyone with a fait accompli: a construction megaproject in midstream, and the promise of gridlock if more funds aren’t made available. Specifically, says Metro chief Kevin Desmond “about 125 daily bus trips and 7,500 daily transit seats will be lost — while tunnel construction and viaduct demolition continues into 2016.”

That’s not to mention that the massive central waterfront renovation won’t finish until the end of 2019, the chance that the tunnel project will go into overtime, or the tolling to pay for the tunnel that is expected to divert more traffic to downtown streets.

(Transit wonks will find City Councilmember Richard Conlin’s reaction amusing: Conlin, reports Lindblom, wondered, “why did the state support extra buses for only half the Highway 99 construction period, instead of until the tunnel opening, scheduled for early 2016?” This is the same Conlin who controversially elbowed past the Mayor to sign go-ahead documents for WSDOT.)

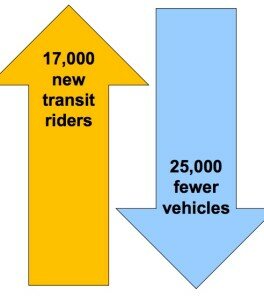

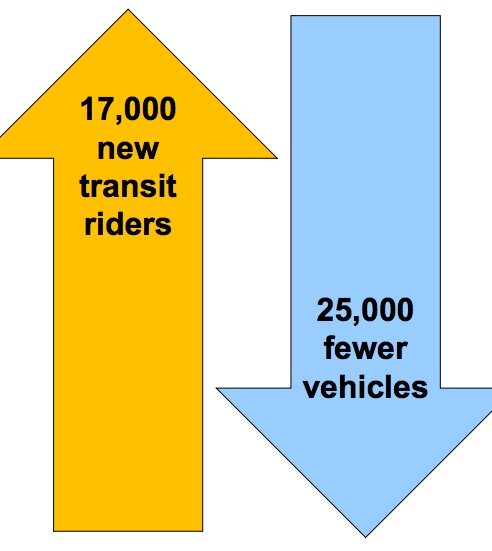

Metro is justifiably proud of what they’ve achieved so far: “Bus ridership on the viaduct increased 22 percent — nearly 17,000 new daily riders,” says Desmond. “There are now 25,000 fewer vehicles on the viaduct every day, a 23 percent decline that is helping everyone keep moving.”

Keep in mind that a 2010 Commute Seattle survey (pdf) found that 42 percent of downtown commuters traveled on public transit — it was the single largest mode of transportation, beating out solo drivers at 35 percent. On an average weekday in Seattle, there are 300,000 transit boardings.

That success cuts no ice with low-information Seattle Times commenters, many of whom seem to believe Metro prefers cadging dollars this way.

Why doesn’t Metro increase fares, they ask? In fact, the King County Council has already approved four fare increases between 2008 and 2011, for a total increase of 80 percent. Currently the peak one-zone fare is $2.50, and $3.00 for two zones. Operating revenue for 2011, at 29.4 percent of expenses, handily exceeded the target of 25 percent.

Why isn’t Metro more efficient, they cry. In 2011, Metro instituted performance audit suggestions that should yield $20 million in savings each year, while scheduling changes are saving nearly 120,000 service hours annually. Transit looky-loos often complain about half-empty buses, but they aren’t half-empty at rush hour — and Metro can only make marginal gains from cost per boarding during non-peak hours. In any event, cutting bus routes or not is often a political decision.

There is one major factor behind Metro’s chronic budget problems, and that is that its revenue is based off sales tax revenue, which slumped during the recession, and is only this year anticipated to reach 2006’s revenue. It was an inverse relationship: the less money Metro had, the more ridership demand increased. In the five years since the recession set in, nothing substantive has been done to change that.

In above story “Metro can only make marginal gains from cost per boarding during non-peak hours.”

What does this mean? A few sentences of explanation would help.

Sorry, you’re right, I could have fleshed that out more, as there are some significant assumptions behind it. Assuming Metro is running close to capacity during rush hours and assuming that those hours are also peak demand (these are both likely true assumptions), the system would be operating close to optimal efficiency even if you still saw coaches running during the day with 5 passengers on them. (It’d be great if Metro provided those statistics, actually — I think rush-hour boardings / rush-hours of service would provide more interesting cost per boarding numbers.)

But let’s take that as the core Metro service: It’s a fictional transit system that offers twice-daily rush-hour mobility to the greatest number of passengers. In some sense, it can’t run often enough because demand is so great during specific times. But this is why it exists: to move huge numbers of people to and from work.

Essentially, then, the non-peak hours of service are provided because of a squishier concern for all-day mobility access and because we happen to have these buses & operators on hand anyway. I’m assuming that non-peak boardings would be less than rush-hour boardings, which is a big assumption. But if so, gains from non-peak cost per boarding (by adjusting frequency, hours of operation) would always be a fraction of the larger rush-hour number, therefore marginal. You can’t increase demand that isn’t there. Reversing peak/non-peak charges so that the off-hours paid more for their costlier service would likely diminish non-peak demand further.