In the wake of Japan’s earthquake and tsunami, I got in touch with Carol Dunn, who works for Bellevue’s Office of Emergency Management, to talk about the job of convincing the community in and around Bellevue to pay attention to the earthquake threat the region faces.

I’ve talked about earthquakes here before, and have a blog about various quakes in the Northwest, but the March 11 disaster brought a new sense of how scary things will get here and on the coast if the Northwest’s subduction zone ruptures in the same way that Japan’s did.

Japan’s disaster has receded from the headlines, and when it comes up it’s mostly in the guise of talk about Fukushima Daiichi, but the example of March 11 still sits as an ominous warning: the question is whether we will heed it. With this in mind, here’s what Carol had to say about the Eastside and why tech companies there need to get ready for temblors.

How do you expect Bellevue and the Eastside to fare in a sizable quake? Will it be helped by its newer buildings built to tougher codes? How will the floating bridges do?

Bellevue and the Eastside have gotten lucky on a number of counts—there is far less ground prone to liquefaction than south King County and Seattle. Most of the building started after the unreinforced masonry period of the 19th century (the type of building found in Pioneer Square and Capitol Hill)—and most high-rises went up after the mid-seventies fashion of building non-ductile concrete structures that don’t handle earthquakes well.

Bellevue does sit right on top of the Seattle Fault Zone, on a section that has broken the surface and thrust itself upward. As such, the area has experienced repeated very intense shaking, much larger than any of the earthquakes we’ve had since the city was founded. Are Eastside buildings ready for that earthquake? It is worth taking the time to work out how well the buildings you occupy handle quakes: Were they built with earthquakes in mind? We have a number of buildings that are up on posts to provide parking underneath. These types of buildings aren’t allowed in California unless they are specifically braced to handle shaking: That isn’t the case here.

An interesting aspect of the floating bridges is that they are designed to handle a lot more movement than more conventional bridges are—they already get pushed and pulled by our huge windstorms. But we didn’t build them with earthquakes in mind. In fact, there are some aspects of the 520 bridge that really aren’t expected to do well in earthquakes—and I-90 runs right along a Seattle Fault Zone strand. Not every bad thing that can happen will happen in an earthquake, but it is pretty likely that we will be losing the ability to use the bridges.

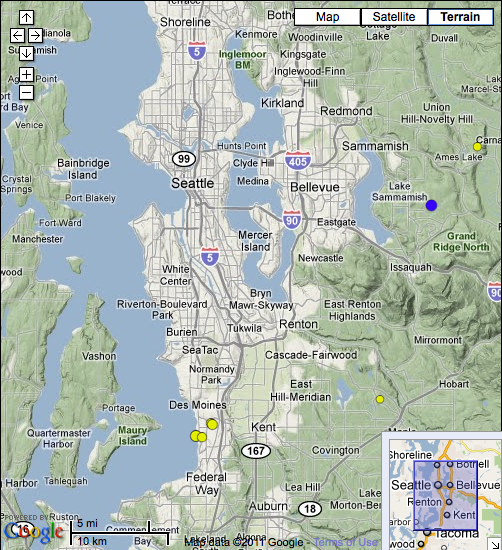

Where are the weakest soils in and around Bellevue: Which areas are most vulnerable to liquefaction and amplification of seismic waves?

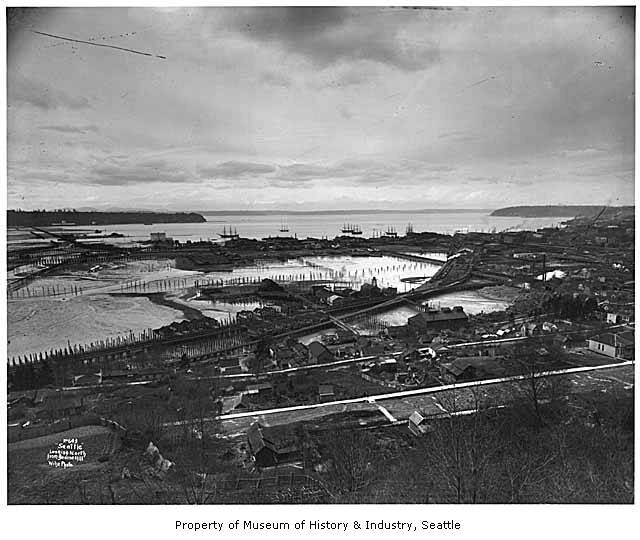

Because of our area’s rich seismic history we have very little bedrock, so our whole area shakes a bit more than other parts of the country. It’s been described as a bowl of jello before. Lucky for us, during the ice age we had massive glaciers that super-compressed the soil in most places. That’s why gardening can be so fun—you try to dig, and the ground is like concrete. Don’t knock it: That is a saving grace for us regarding earthquakes in many ways. Not all of our ground matches this type of soil though: Areas where water has flowed frequently have built up layers of looser sediment that is waterlogged. These are the areas that are likely to experience liquefaction. During shaking, the looser sediment layers move around independently, so the dirt acts like a liquid not a solid. Heavy objects on ground prone to liquefaction can sink into the ground, sewer pipes and wires can float up. Buildings built on ground prone to liquefaction are likely to experience more intense ground motion.

How does the Eastside’s high-tech economy relate to the earthquake threat? Are the tech companies more attentive about preparedness? Has this changed after the Japan earthquake/tsunami/nuclear crisis?

In my experience, the larger high tech companies take the earthquake threat very seriously, and have worked quite hard to build resiliency. Not only that, companies like Microsoft reach out to help the community get ready as well. They’ve been working with our local Red Cross to get their staff trained in disaster response, but also to discuss ways that they can support the area after severe storms and earthquakes. I’ve found that successful companies build risk identification and reduction into the way they do business. It makes sense—identify what can go wrong in your life, and take steps to make it not happen. Each thing you keep from going wrong is one less thing that goes wrong—success becomes much easier. That is what personal disaster preparedness is about as well. I do think the situation in Japan has been a wake-up call for most companies. These worst-case scenario earthquakes we try not to think about do happen: It really is important to identify and reduce as many risks as we can while we have the chance.

What kinds of impacts do you think a big local quake or a subduction zone quake would have on this area’s manufacturing and tech industries? It seems that Boeing in particular would be very impaired by damage to its local factories and the loss of transport networks.

If we have a local surface earthquake from the Seattle or Whidbey Island Fault Zones, it isn’t going to be fun, but I suspect recovery will come pretty quickly—we will be having help come from all sides the moment word gets out that there was a major earthquake. When we experience the next subduction zone quake—the type Japan just experienced, and Chile before that, help is going to take a lot longer to reach us. The locations that would normally be rushing to our aid will have also just experienced a massive earthquake. We need to be ready to reach out and help each other. We will be our own rescuers, we will have to be.

Companies do need to have a plan for how to recover if they face large scale disruption—this is true for any company located anywhere. We have our risk of earthquakes, other areas have tornadoes, wildfires, hurricanes, and human caused problems as well. The more companies can do to increase their ability to function when things are difficult, the better the entire community will fare. Being able to get the population back to work is so important—both psychologically and economically.

And, would King County be looking at similar types of losses of water supply, gas, heat, power, even food, that we’ve seen in Northeast Japan for over two months now?

I read that after the earthquake in Kobe, Japan in 1995, the water pipes were broken every 1,000 feet. Seattle has a map of all of the water supply problems created by the moderate size quakes that we’ve experienced. A large quake would definitely cause more leaks.

Because we can predict what can go wrong means that we can build ways to reduce the impact of it going wrong. We know that we will probably not be able to get water from the pipes—have back up water saved. If you have a water heater, learn how to turn it off, and know what you need to do to get water from it in an emergency.

This is Part 1 in a three-part series.