Were Martha a real person and alive today she’d be 103 and George would still be six years her junior. These giants of the American stage have been battling it out since 1962 and if the current production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (through May 18 at Seattle Rep.) is any indication they have plenty of fight left in them and plenty more to say to us.

The Seattle Rep production avoids the pitfalls and delivers the goods, letting Edward Albee’s masterpiece work its magic. In a week or so it will be a must-see event but this week the gears aren’t quite meshing.

The machine those gears drive is a booze-fueled trip through the wee hours. Here the bonds of marriage support and suffocate. Intimacy is betrayed, vulnerability is exposed, and we see ourselves as individuals and a nation with heartrending clarity.

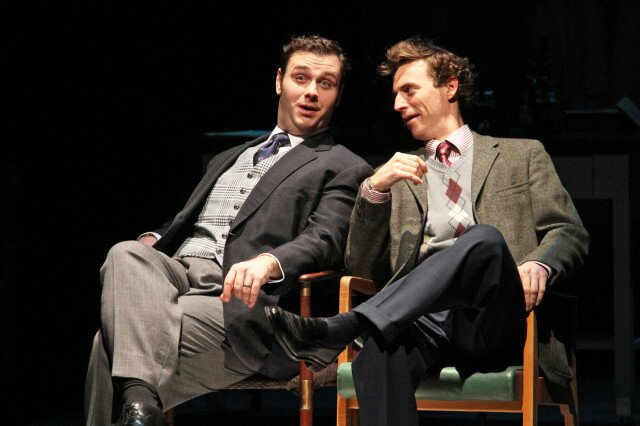

It is early September, which is New Year’s Eve in mid-century American academia. George (R. Hamilton Wright), a middle aged history professor, and his wife, Martha (Pamela Reed)—the longtime college president’s daughter—come home tired and tipsy. George is ready for bed, but Martha has invited a new hire, Nick (Aaron Blakely)—a biology professor—and his wife, Honey (Amy Hill), for a nightcap and more.

Nick and Honey seem like a conventional, unexceptional couple. They are polite and tidy. They seem a little bored and boring. George and Martha are none of those things.

Honey is sweet and demure. Nick is a clean cut all American, not defined by his profession. In fact it takes some doing for him to convince George and Martha that he is in the biology, rather the math department.

George wears his erudition on his sleeve. Martha is at least his equal, intellectually, but more important, she is an excellent sparring partner. Most of their conversation involves very serious sounding verbal duels.

It is obvious, almost from the outset, that George and Martha’s scrapping is an expression of love. They are passionate. They play with words and fantasies, shoving shivs at every opening, pausing (a bit too much in this production) to savor the fun as they get one another worked up.

It’s all games. It’s play, and therefore, it is very theatrical. Director, Braden Abraham, points this out a little too overtly creating stagey scenes before period-perfect god-awful articulated room dividers that evoke curtains on a proscenium.

The great actor and playwright, Tracy Letts (who played George in the 2012 Broadway production) has suggested that most couples envy George and Martha. They may seem brutal with one another, but after a couple decades of marriage they are still engaged and involved with one another. However no one could envy Nick and Honey.

This young couple, new to the faculty, stumble into George and Martha’s arena where they are coerced into the bloodsport. Their insertion into George and Martha’s private lives provides the meat of the play. Problems must be solved, secrets contained, and fantasies unmasked. George and Martha do these things in the only way they know how: Let the games begin.

Reed and Wright play the games well. Reed brays with the best of them and leaves herself enough room to build. Her climax is full of jagged edges that give Martha a surprising frailty. She shatters too soon.

Wright gives us George played with a touch of Groucho Marx and Woody Allen. This is not the most dignified George, but a more knowing clown and one we love easily.

Blakely holds his own with Nick, making him a force to be reckoned with. One doesn’t believe he’ll ever strike George but he could. Amy Hill’s Honey refuses to get lost in the background. She’s a strong enough presence that even when she says nothing we look to her for a non-verbal response. She never disappoints.

The characters in this play consume a dangerous amount of alcohol. SRT’s Keeping Up With Martha drink offer (must be pre-ordered at the box-office) is less ambitious and may help attentive audience members keep their cool through the onstage fireworks. The three drink flight features local booze.

My trusted drinking assistant declared the pre-show champagne cocktail inoffensive but boring. The first intermission Old Fashioned was better, with a pleasant surprise in the maple syrup (apropos of New England academia). The second intermission Gin Manhattan offended her (gin in a Manhattan!) but I found the gin softened the cough syrup quality of the sweet vermouth.

And yes, it is a three-act show, but there isn’t a slow moment. It is a tense three hours of laughter, anxiety, and wonder. In the end we join Nick, unreservedly murmuring “My God, I think I understand” but also, we continue to wonder

Fifty-two years on this play still feels topical. Academia has changed (a little), we drink a little less, and women are more liberated but the topics remain current. Genetic engineering, evangelicalism, the objective science, technology, and math studies opposed to the subjective liberal arts, all play important parts. All these are still part of our conversation today.

{Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf plays at Seattle Repertory Theatre through May 18. Tickets and more info can be found here.}