We need to invent the word “throwforward” to counter the existence of throwback. Watching Yussef El Guindi’s play Pilgrims Musa and Sheri in the New World, I kept thinking of Paddy Chayefsky‘s kitchen sink realism, which influence we are sorely lacking. But El Guindi’s play has nothing to do with theatrical nostalgia–Chayefsky couldn’t have written this (not least because of the anal sex reference). But I think he would have applauded.

It’s a good sign, then, that ACT’s Pilgrims Musa and Sheri in the New World (through July 17; tickets) is a world premiere. Director Anita Montgomery saw in El Guindi’s script—back when it was just a script, just a workshop, just a festival entrant–the “humor and humility” that keep its exploration of the immigrant experience a personal and affecting story.

Whatever else you want to say about it, Pilgrims is, after all, the story of two lonely people who meet and fall in–possibly maybe–love. You meet Sheri and Musa as they’re climbing the stairs to Musa’s ratty apartment, both very nervous, they hardly know each other. Sheri (Carol Roscoe), who has a habit of speaking every thought out loud, wonders if she’s just walked in to a serial killer’s place.

Jennifer Zeyl’s set is also in the kitchen-sink realism vein–there’s only one set piece that calls attention to itself as a theatrical construct (Musa’s taxi). Otherwise, you almost assume that someone broke into a rundown apartment and stole the furniture to reassemble on ACT’s stage. ACT’s sunken stage even lets you look downstairs. It’s a fully convincing exercise in anti-spectacle, right down to the bare doughnut fluorescent light. (L.B. Morse’s lighting accommodates bare fluorescent, bare incandescent, candlelight, and streetlights.)

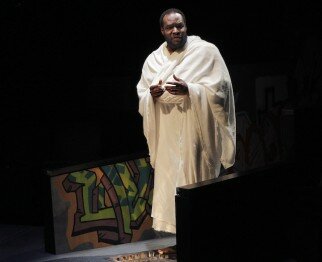

“We are all, basically, wonderfully,” and I am paraphrasing from memory, “the same,” says Abdallah (Anthony Leroy Fuller), Musa’s roommate. You have the privilege of dismissing this claim as cliché if you’re in the majority, but coming from an immigrant it’s a challenging moral claim.

He’s dressed in white robes, an apparition who’s gone on hajj, and this is the play’s argument, too, though not in the gross “under the skin we are all brothers” sense. Much of the play turns around the fact that people are different, want different things from life. What it celebrates is the shared specificity of desire.

There’s nothing particular about Musa and Sheri, really, that suggests they should work as a couple. Who can explain it? Who can tell you why?

Musa (Shanga Parker) drives nights in his taxi; Sheri works nights as a waitress. She claims she’s not the kind of woman who just follows a guy home, but, in fact, you suspect that she has a history of doing things like that. What the hell, why not? Musa has learned his English from crime fiction. Parker plays him as someone who’s not home when he’s home, still jumpy, diffident. He has plans for a better place once he saves the money up, but if he continues to let his Somali friend Tayyib (Sylvester Foday Kamara) pay him in Scotch for taxi rides, how long will that take?

El Guindi doesn’t really try to explain the passion between Musa and Sheri; it just is. Neither Musa nor Sheri is perfect. Musa is non-confrontational to the point of incurring calamity. Sheri’s mouth is always two steps ahead of prudence. (It’s hilarious, this is a very funny play, but it’s not a sitcom–you can see how Sheri 24×7 would be an acquired taste.)

Roscoe gives a fearless performance as an admittedly flawed woman who is throwing herself at someone who is, just this once, inclined to catch her. It’s not always pretty: She’s “fleshy” as another character sums her up. (Melanie Taylor Burgess’s costumes give her discount store sex appeal.)

There’s a great sense of place in El Guindi’s play, and this is essential in a work about immigrants: It’s important to know there’s a corner store, that you can hear the couple upstairs battling it out (Brendan Patrick Hogan’s sound design), that Musa shows up at Sheri’s diner to see her. Place is at the heart of all this. El Guindi wants to show that place can be temperament, too–not simply cultural. Americans are people who take up the American ideal of successful reinvention, who feel at home there.

This is how you earn your citizenship, by getting on board with self-determination–and that’s not something you can be born into. It’s a choice–that’s why Sheri is a pilgrim, too.