The Project Six (at ACT Theatre through March 30) program is a little shorter than anticipated (a third work had to be dropped due to a dancer’s injury), but it still makes for a fully satisfying evening of dance. The two works by choreographer Jason Ohlberg, Departure from 5th and Gloria, reward close attention: They’re often protean exercises that photography, in registering the apex of a pose, misrepresent.

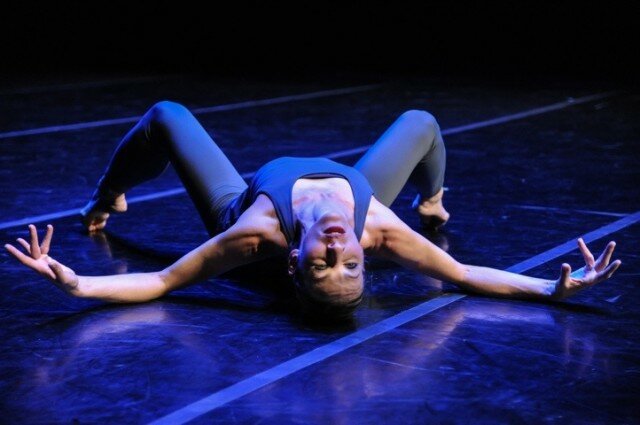

Ohlberg’s dance rarely finds a resting place, unless it’s on the floor. Port de bras keeps upper bodies in near-constant motion. The Seattle Dance Project troupe skews toward ex-ballet, so they can meet these demands without the stage degenerating into windmilling arms. The degeneration in Departure from 5th is its theme. Incorporating dancer interviews conducted by John Carroll (Ohlberg edited them down), the work meditates on the effects of being “not good enough” — whether that’s the shape of the body, or a judgement about skill.

It opens with a guest trio of Fates (Irene E. Beausoleil, Narissa Herndon, Micaela Taylor) sweeping through the space in marmoreal gowns by Carol Franklin, their arms sickling like a scythe. They reappear throughout the piece, moving dancers around the stage with a hand lightly held on the nape of a neck.

Each SDP dancer has a sort of soliloquy that shows them off as they criticize, light-heartedly or more seriously, the narcissism inculcated in their younger selves.

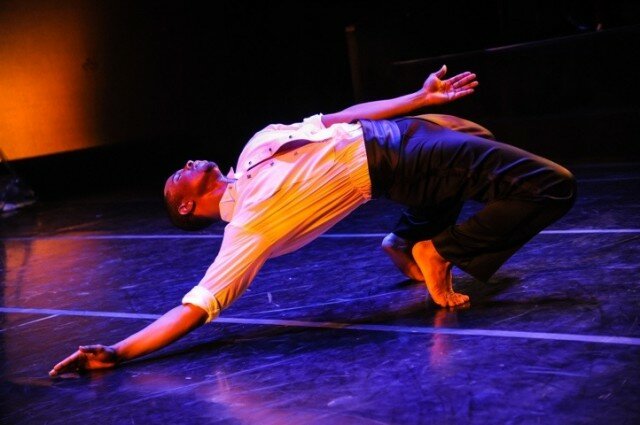

Betsy Cooper elevates from floorwork to jumps. Alexandra Dickson may rue her “sturdy legs,” but her footwork is clean and snappy; Michele Curtis is another exponents of a technique so honed it can seem machine-like. Timothy Lynch extends his left foot, toes tucked, and pirouettes, as his voiceover recalls working to perfect that. Iyun Harrison wrestles with the heterosexist “princely” physique he embodies, while Christopher Montoya recalls trying to dance “taller.” (In fact, he possesses an outsized, charismatic courtliness.)

A ballroom dance interlude breaks up the rigor with a group grapevine, shimmies, and hip shakes. Dancers love to dance, even as the lights (by Peter Bracilano) dim, and the Fates cut across the stage with a sheet, enveloping everyone. It’s an engaging, multifaceted work. Ohlberg can be a little too fond of port de bras here — its impact is less when it’s everywhere at once — and he too often leaves dancers in configurations where they must dodge another dancer as they hurry to the next place. But on second viewing, it’s just as affecting.

Gloria, set to Vivaldi, is a fast-moving sequence of shorter dances tied together by gestures that run through the work like threads in a tapestry. There’s Dickson’s cocked elbow; the ensemble with palms together, arms rising up; a repeated drop to the floor in a faint (sleep, or temporary death — they revive). Ohlberg and Montoya lift Lynch — all in a peasant-y brown– aloft. Lynch stands with one arm raised, index finger pointing up to heaven. The women slap their thighs to a common beat, and trade it to the men. Then Betsy Cooper arrives, running forward, managing to seem completely, utterly present. Ohlberg has a beautiful, athletic solo in the glare of an overhead spot (Bracilano’s lighting, again), then a quartet forms, and then the full company reassembles for “Gloria in Excelsis,” against a bright-yellow projection background. The women kneel, and then Cooper, alone, walks slowly upstage as the lights dim. It’s celebratory of a life in dance, and of the communal and spiritual feelings that takes your attention off yourself, toward the shared or transcendent experience. When it’s done, you want to hit Repeat, though SDP’s sweaty troupe would have been hard-pressed to follow through.