The light seems to drip down planes that are the front and back of Andrew Bartee, at the outset of L’Effleuré. Lighting designer Michael Mazzola catches Bartee from all angles throughout the course of Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s dance piece, whether “elastic technician” Bartee is soaring in a leap or sinking to his haunches in a grand plié, pulsing slightly to a rhythm like breathing or heartbeat. A sinuous movement travels slowly through his core, a leg extends skyward, he pirouettes — all with the gravitas of someone not simply at home in his skin, but almost too-exquisitely aware of it (with his back to the audience, Bartee manipulates his shoulder blades, and skin transmits the subcutaneous movement).

L’Effleuré is a mash-up of referents — it’s French for lightly touched, or caressed, but the program notes mention Louis XIV, the Sun King, too. The strutted torsions are about a muscular elegance, the rose-petal palms and rose-mouth advertising an easily-bruised sensitivity. (It looks great, but Bartee confesses afterward he’s mainly trying not to drool as he bites down on the stem.) At one point, Bartee sinks forward on his knees, his palms up as if in supplicating prayer, and then they look like rose stigmata. The music is Vivaldi’s “Stabat mater dolorosa,” so the stigmata may not be unintended, though here they are transformed.

The other stand-out work in Whim W’Him’s program Third Degree (last weekend at the Seattle Center Playhouse) was Olivier Wevers’ I don’t remember a spark, a journey through dark and contradictory crevices in the choreographer’s mind. The work grew out of a wide-ranging interview Wevers had sat through; it begins with Tory Peil entering the stage through an aisle in the audience’s seating area, white suitcases in tow. She cocks her head and freezes as a Wevers voiceover says, “I don’t remember a spark.”

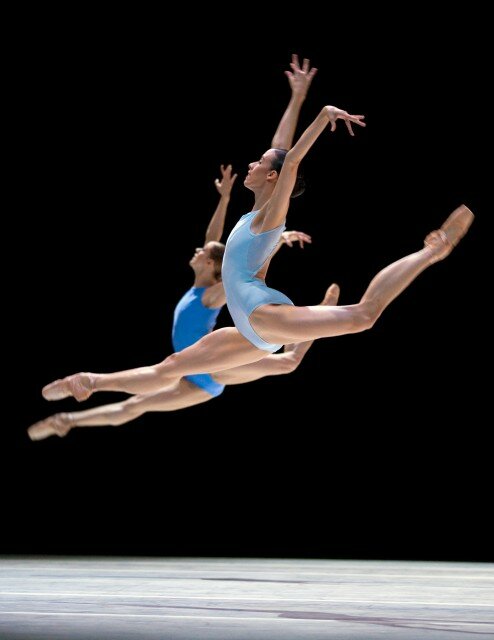

It’s full of wry humor and deprecating touches, but undeniably also suffused with sadness and dislocation. As Peil gains the stage and perches on her suitcase, other dancers enter, one by one, with their luggage and shoo Peil from place to place. You hear the sound of travelers in a station (composer Brian Lawlor’s sprawling sonic environment includes keyboards, rhythms, distorted speech). “I dream impossible things,” Wevers says, as Andrew Bartee flies, lifted by hands, across the stage.

You hear Wevers discourse about his choreography, where it comes from, what his interests are, and the choreography often comments on that. When he says he doesn’t want black, he wants purple, it draws attention to the dancers wearing nothing but black. When he says “graceful” the dancers wobble; when he says “seamless” they come up short in sequence, bobbling. The audience laughs out loud at a line dance that acts out verbal-filler tics (Wevers told me it came from listening to himself “um” and “ya know” through interview tapes) — the dancers all rub their chins reflectively.

The heart of the work is a duet between Bartee and Peil, illustrating a couple whose personal space looks like Swiss cheese, with secret tunnels from one to the other. Some of Wevers’ most original work comes in his pas de deux, and the movement idiom his couples seem to have invented, like a secret language. Here you see a lightness and heaviness, a body dragged dead-weight on the floor by its arm, then something tightens, and everything lifts. Outstretched hands meet and curl around foreheads, necks. Peil and Bartee run through dance prepositions: above, beside, below, upon, sliding through another’s arch, arms reaching as if to tie themselves together. Peil has gained that ability to be the step, as if it’s a thought she’s having, and Bartee thrives on that spontaneity.

In the shadows dances another Wevers preoccupation, the “monster”: a swarming of the dancers (Bartee, Peil, Mia Monteabaro, Lara Seefeldt, Sergey Kheylik) their arms interlocking, entangling, one of them struggling to break free with a mimed shout, then pulled back in. After, Monteabaro has a solo in front of a barred light that casts a huge black shadow. As Wevers discusses his own insecurity, Bartee performs a Robbins-esque “anixiety” solo behind a scrim, shoulders hunched, fingers clawed, at one point he’s bent over backwards. It’s like if you make cheeseburgers and people like them, narrates Wevers, tragicomically, now you’ve got to make a lot more cheeseburgers.

Bartee has his own work in the show, This Is Real, about “tension between friends” and set to music by Lena Simon. He’s expanded it from a shorter work, to let various combinations play out. Initially, Peil and Monteabaro are dancing in perfect synchronicity — you’re just watching a stream of ideas unfold, arm gestures and backward steps — and then Sergey Kheylik enters and the mood goes south. Kheylik is a compact, curly-haired fellow with slightly insolent posture, and you see Peil size him up and decide to bite. Monteabaro is having none of it, slapping Kheylik’s chest and pushing Peil down. When Kheylik doesn’t back off, she jumps him. Things never get that volatile again, but every time Kheylik reappears, Peil and Monteabaro having found their rhythm, there’s a frisson that runs across the stage.

Lara Seefeldt and Jesse Sani make a feast of a remounting of Fragments, Wevers’ 2007 prize-winning work that employs Mozart arias to make elbow-room for dance that is a bit more full-throated. Seefeldt and Sani are wearing deconstructed corset-and-gown numbers by Christine Joly de Lotbiniere, Seefeldt every inch the Mozart ingenue. They can dance prettily, as befits Mozart, but you’ll also see them bend over backward with a scream’s rictus on their faces, or seated, they beat their feet in tiny pas in a widening arc, evoking a coloratura run. Sani’s solo, in which he steps out of his dress, and begins an exercise in uncorseted, slow articulations, is a show-stopper.