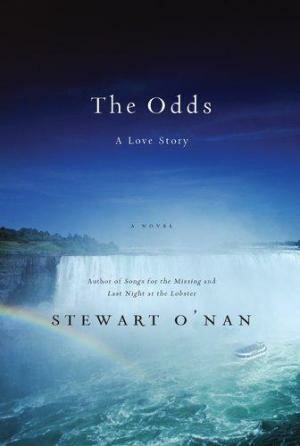

Stewart O’Nan reads from The Odds: A Love Story at the Seattle Public Downtown Library at 7 p.m.

Now, well into middle age, he’d changed shockingly little. If, as he liked to think, his greatest strength was a patient, indomitable hope, his one great shortcoming was a refusal to to accept and therefore have any shot at changing his fate, even when the inevitable was clear to him.

I don’t want to quote too much from The Odds, by Stewart O’Nan, because it’s a small book, about 180 pages, and his style isn’t the pyrotechnic kind that, in a paragraph, leaves you wide-eyed. I’d just end up giving things away. The Los Angeles Times called him “the spokesperson of the regular person,” and you can see what they were getting at, but O’Nan’s gift is to somehow, through building up the stream of life’s matters of fact, surmount them.

I don’t want to quote too much from The Odds, by Stewart O’Nan, because it’s a small book, about 180 pages, and his style isn’t the pyrotechnic kind that, in a paragraph, leaves you wide-eyed. I’d just end up giving things away. The Los Angeles Times called him “the spokesperson of the regular person,” and you can see what they were getting at, but O’Nan’s gift is to somehow, through building up the stream of life’s matters of fact, surmount them.

Here, a 50-something couple who have smashed up bankrupt in their marriage and mortgage, are embarked on a last, prodigal trip to Niagara Falls, where Art has the insane notion of going double or nothing, so to speak. His wife Marion is along for the ride, but regretfully, as this undersold recap illustrates: “Her entire life had not been a ruin. There were seasons she’d keep, years with the children, days and hours with Art, and, yes, despite the miserable end, with Karen.”

Though it begins with them on a bus, swapping the terrible, unadorned small talk of people who have lost the ability to surprise each other, O’Nan is setting out, let’s say, on a slippery wire across the falls, like a literary Philippe Petit. Small steps, small steps, and suddenly you’re in the middle, a torrent beneath you. Everything must be perfectly weighted: Art’s doggedness, Marion’s habitual light rancor and dodges, the flashbacks to where the money went, the “keeping up appearances” with Facebook boasting about seeing Heart, live.

In summary form, this has every appearance of being a book about something: “our time,” perhaps, the pissed-away end of the American Dream, but O’Nan makes no great effort to paint Art and Marion as typical in grander ways–he insists on their uniqueness just in living as they do, in having lived as they do. They come to feel like people you might have run into on a bus, spoken with a bit to pass the time. Balanced against their casino scheme, O’Nan places the chance that they have already gotten lucky–as lucky as people get in love.