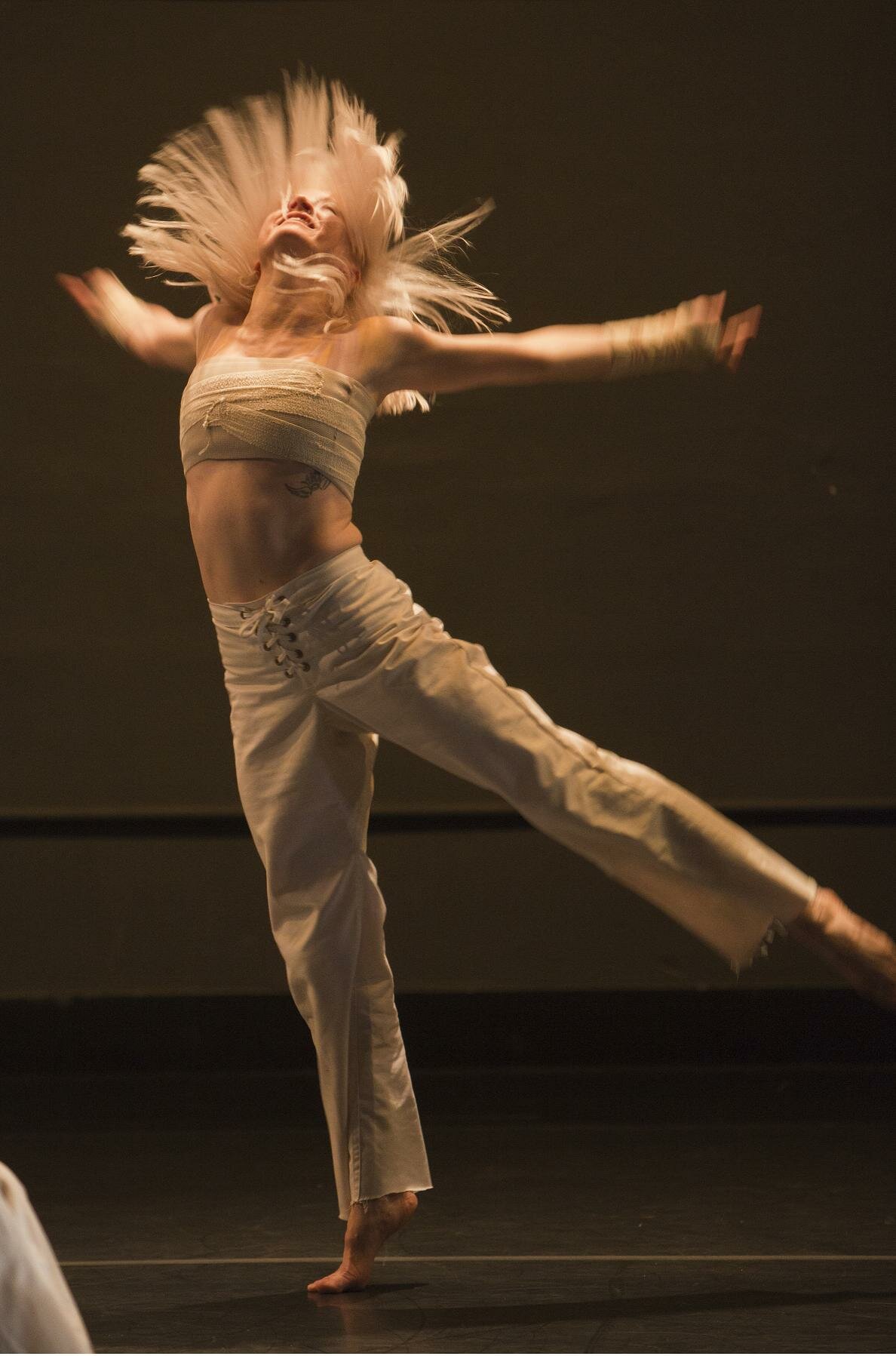

Twenty musicians scattered around the cavernous Chapel Performance Space, some holding instruments, others armed with cardboard boxes. Their performance began unassumingly, the quiet tapping of fingers on cardboard punctuated by occasional soft bleat from an instrument or two. After awhile, the musicians began to wander around the room, sometimes gathering around a conductor in small groups of two or three to perform a short scored passage. Meanwhile, the background soundtrack of cardboard tapping and instrumental noises continued, remaining a constant force throughout the performance.

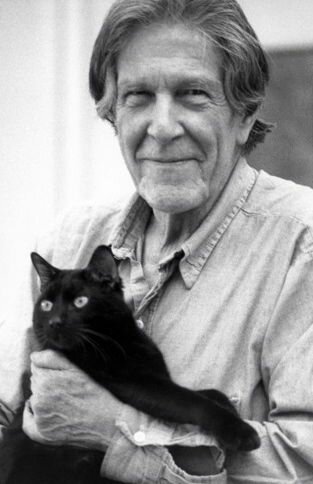

This performance of John Cage’s Etcetera is the sort of idiosyncratic musical event to be expected from the American composer. Even twenty years after his death, Cage’s music continues to inspire and challenge audiences. One of the most influential figures of the 20th century avant garde, Cage’s works remain fresh and relevant today, pushing us to expand our musical boundaries and encouraging us to experience sound in new ways. This year marks the hundredth anniversary of the composer’s birth, inspiring numerous “Cage Centennial” celebrations throughout the world. On November 9, the Seattle Modern Orchestra (SMO) presented a John Cage retrospective of their own, highlighting a variety of the composer’s works, from large ensemble works like Etcetera to smaller scale pieces for just three or four musicians.

The atmospheric Chapel Performance Space, located at the top of Wallingford’s historic Good Shepherd Center, provided an ideal setting for the evening’s sonic events to unfold. The room’s large open space and level floor enabled the musicians to wander among the audience and play from different parts of the room, lending an immersive atmosphere to the performance.

The highlight of the evening was a performance of Cage’s Concerto for Prepared Piano and Chamber Orchestra, featuring pianist and Cage scholar Stephen Drury. This meandering piece, completed in 1951, is one of most ambitious works Cage wrote for the prepared piano. The work eschews melody and harmony, favoring a loose rhythmic structure over which the piano and orchestra splatter seemingly-random blots of sound. The overall effect is sparse, enabling the listener to experience the blending of prepared piano and orchestral sounds. SMO founder and conductor Julia Tai maintained an effective balance between soloist and ensemble, highlighting Cage’s juxtaposition the prepared piano with the full range of the orchestra. Drury’s expert preparation of the piano followed Cage’s complex specifications, with metal screws, strips of fabric, and plastic pieces placed between the strings to alter the piano’s sound.

Two other representative works on the program were Cage’s Trio and Living Room Music. These short pieces, written for small ensembles, were performed by members of the Seattle Percussion Collective. Trio explores the variety of sounds that can be created by wood-block instruments. The ensemble’s performance of the whimsical Living Room Music was the most fun performance of the evening. This 1940 work, written for a quartet of musicians, requires the performers to create sounds with objects that can be found in a typical living room. SMO’s performance incorporated percussive sounds drummed on vases, books, tables, and a toy boat. During the movement “A Story”, the members of the quartet chanted snippets of phrases in a variety of rhythms, creating an effect that was reminiscent of contemporary spoken word poetry.

Cage’s admiration of the natural world was represented by the arduously-named piece, “But what about the noise of crumpling paper which he used to do in order to paint the series of ‘Papiers froissés’ or tearing up paper to make ‘Papiers déchirés?’ Arp was stimulated by water (sea, lake, and flowing waters like rivers), forests”. This introspective work, inspired by visual artist Jean Arp, was performed by several members of the Seattle Percussion Collective. From different posts around the room, each musician played a small collection of percussion instruments, including crumpling paper, pouring water, clacking rocks together, and tapping pots and pans. The overall effect was meditative and relaxing.

The evening’s performances were augmented by segments from John Cage: I Have Nothing to Say and I Am Saying It, a 1990 documentary about Cage’s life and works. SMO artistic directors Julia Tai and Jeremy Jolley provided additional commentary on the pieces on the program. This multimedia format was accessible, educational, and engaging for both newcomers and experienced Cage aficionados. As a retrospective, the event covered a lot of ground, presenting a wide spectrum of Cage’s compositional styles, guiding the audience on an exploration of the composer’s unique sonic world.