Seattle Symphony concertmaster Alexander Velinzon has an insanely busy schedule, but he still makes time where possible to play chamber music. Friday night saw his first appearance with Simple Measures, the group which recreates the meaning of the word “chamber” in chamber music: music written to be performed in intimate venues, originally concerts in privately owned salons.

The major work on the program was Beethoven’s Piano Trio in B-Flat, the “Archduke,” which he performed with Simple Measure’s founder, cellist Rajan Krishnaswami, and pianist Mark Salman. (The concert is repeated this Sunday at 2 p.m., downstairs at Town Hall.)

A small venue makes it possible for anyone in the audience to see the interplay between the musicians, the way their eyes are continually not only on the music but each other, watching tiny body movements to judge exact entries, sensing changes in tempo, dynamic, or phrasing (of course, this also takes for granted their discussion and practice beforehand). And, which is typical in chamber music, how much the musicians are enjoying themselves.

This was true Saturday at the little chapel at the Good Shepherd Center in Wallingford, where Velinzon and Krishnaswami seemed to be having a blast, the two playing together as though they’d done it all their lives. Asked afterward, Krishnaswami said they’d had five rehearsals only, but that there had been an instant musical rapport between them.

Simple Measures plays in coffee houses like Q Café in the Interbay area, community centers like the one in Mount Baker or, as on Saturday, in the chapel: places where people can come casually dressed, bring the kids, listen to the musicians warming up and practicing bits of the program, chatting until the performance starts. Simple Measures may be deliberately casual, but the musicianship is not. Now in its eighth season, it has gained a reputation for excellent performance and fine musicians are delighted to perform with it.

This season’s three programs have been planned around, respectively, Rhythm, Melody, and Harmony. The program always comprises several short excerpts in the first half, and a complete work for the second, in Saturday’s case the “Archduke.” For this Harmony program, Krishnaswami chose examples of Baroque, Classic, Romantic, impressionistic and modern harmonies, the performers giving brief explanations in a mini-Music Ed 101, and asking the audience after each piece for their impressions.

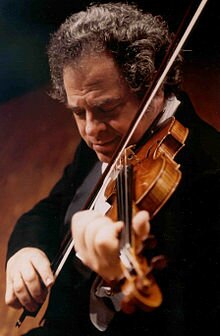

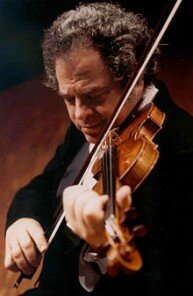

Velinzon gave an eloquent performance of an unaccompanied Adagio from Bach’s Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Major, not attempting to recreate Baroque style, but coloring the piece with different shades of vibrato, and demonstrating beforehand how the melody connected the chords and how the bass line descended.

One of the most beautiful works, the impressionistic Allegro from Ravel’s Sonata for violin and cello, had the two instruments interchanging range with the cello sometimes on top. The two performers sounded closely attuned to each other, so that phrases passed from one to the other had a matching floating approach or emphasis, a delight to hear.

The gifted clarinetist Sean Osborn, a regular with Simple Measures, appeared for just one terrific item, the first movement of Bartok’s Contrasts, which had the clarinet flying in spirals before it dies away at the end in modern harmony with violin and piano.

Classical Mozart, Hindemith pushing the harmonic envelope, and Romantic Arensky also made appearances in this very well designed group of short pieces.

Unfortunately, as with so many true chamber music performances today that include piano, the intimacy of the space was overpowered in performance. A grand piano is a massive instrument with big volume potential, suitable to be heard at the far ends of big concert halls. The piano lid is open to its furthest extent to allow more sound out and to direct it towards the audience. This is all very well at Benaroya Hall (2,500 seats), or even at Meany Theater (1,300 seats), but there’s no need for maximum volume in smaller locations.

Do we really need all that sound at Town Hall (900 seats), Nordstrom Recital Hall (540 seats) or at the Good Shepherd Chapel (150 seats)? Surely not. It would help if pianists decreased the height of the lid to four or six inches, or had it down altogether in music which requires a lighter pianistic presence. After all, string players tailor their vibrato to the requirements of the music. Why not pianists also?

Modern stringed instruments are capable of louder sound than Baroque strings, but that is dwarfed by the difference between pianos today and the early pianos used by Mozart and Beethoven. So playing in a trio for piano, violin, and cello, like Beethoven’s “Archduke,” in a tiny venue like the chapel, a grand piano with the lid up creates an imbalance of sound.

This isn’t to say that pianist Mark Salman didn’t play with sensitivity Saturday night. In softer passages, his playing was clear, his touch gentle, all the notes well phrased and present, his ensemble excellent. The “Archduke” andante movement in particular was gorgeous and balanced between all three instruments. However, whenever the dynamic markings went higher than mezzo forte, Salman’s fingers seemed to grow steely and he played at a triple forte level. One could see in his shoulders the force with which he hit the notes. The piano sound dominated the music at these times.

Nevertheless, the concert as a whole gave considerable pleasure, as demonstrated by the applause at the end.