The Seattle Symphony performs Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on Saturday night, December 31, at 9 p.m. at Benaroya Hall. Saturday’s New Year’s Eve concert will be followed by a gala celebration with drinks, dancing, and a midnight countdown. More details and tickets are available at the Seattle Symphony website.

It’s safe to say that virtually everyone knows Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. The work’s famous “Ode to Joy” melody, taken from the final movement of the Symphony, is one of the most recognizable tunes in Western music. The Ninth’s uplifting message and epic scale, which combines orchestra, chorus, and vocal soloists for a grand finale, makes this piece a favorite for the holiday season.

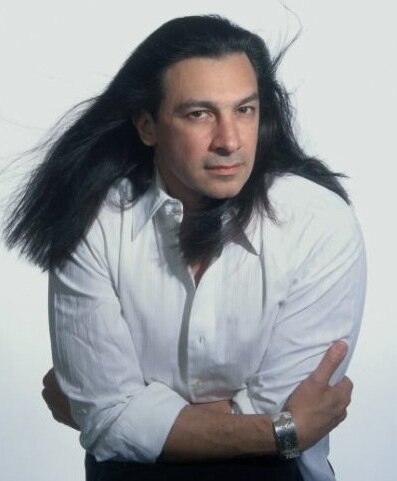

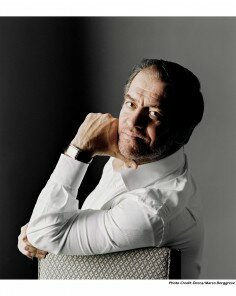

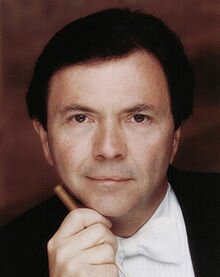

The Seattle Symphony has an annual tradition of ringing in the new year with performances of Beethoven’s Ninth, and this year, Conductor Laureate Gerard Schwarz returns to the podium at Benaroya Hall for these popular concerts. Performances began on Wednesday evening and will be held nightly, culminating in a special New Year’s Eve concert and gala on Saturday night.

Last night’s performance brought a festive atmosphere and diverse crowd to Benaroya Hall. It marked a special day for the Seattle Symphony: The 108th anniversary of its first concert.

Although this fact wasn’t mentioned at last night’s concert, everyone seemed to be in a celebratory mood, from the musicians to the audience. The program was very family-friendly, featuring vivid and colorful pieces guaranteed to enthrall both children and adults alike. In addition to Beethoven’s Ninth, the Seattle Symphony performed a suite of excerpts from another holiday favorite, Engelbert Humperdinck’s fairytale opera Hansel & Gretel.

The program opened with the Suite from Hansel & Gretel, which is comprised of five musical interludes taken from scenes in the opera. Humperdinck, a colleague of Richard Wagner, took cues from his celebrated contemporary by using rich orchestral textures and complex harmonies, evoking a fairytale landscape both enchanting and perilous.

After a majestic brass fanfare at the beginning of the suite, the woodwinds paint a whimsical picture of Hansel and Gretel frolicking in the forest and eventually stumbling upon the witch’s gingerbread house. Humperdinck’s writing calls for a rich string texture, which helps create drama when the witch is defeated and the children dance a celebratory waltz. The Seattle Symphony string section was up to the task, creating many lovely and exciting moments.

The audience returned from intermission eager for the epic majesty of Beethoven’s Ninth. The work opens dramatically, beginning with small chirps from the string section and building until the orchestra is playing in full force. Maestro Schwarz did an excellent job of maintaining the dramatic sound over the course of the first movement. The second movement is dominated by a fugue theme that begins in the string section and echoes throughout the movement, and the French horn and woodwind sections gave particularly fine performances here, especially Seth Krimsky on bassoon.

After a slow and lyrical third movement, the fourth movement begins with a roiling storm that musters the entire orchestra. As the storm subsides, strains of the “Ode to Joy” theme begin to peek through, finally emerging in full form in the low strings. The doublebass section sounded fantastic in those first, muted statements of the theme.

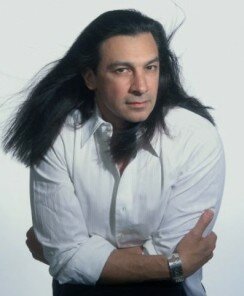

After the “Ode to Joy” theme is tossed around the orchestra a few times, the chorus and vocal soloists step in with tidings of joy and praise. The text they sing is based on a poem by Friedrich Schiller, with alterations by Beethoven himself. This year, the four soloists joining the Symphony are soprano Christine Goerke, tenor John Mac Master, and the husband-and-wife team of mezzo-soprano Luretta Bybee and bass-baritone Greer Grimsley.

Grimsley’s powerful voice made a majestic entrance and set the mood for the rest of the epic finale, which brings together orchestra, chorus, and soloists in various configurations. Mac Master was spot-on in the famous tenor solo. The Seattle Symphony Chorale, led by Joseph Crnko, gave a spirited performance that added even more excitement and energy.

Last night’s rousing performance inspired and excited many audience members. As I was exiting Benaroya Hall, I kept overhearing people raving about how much the musicians and singers seemed to enjoy themselves. Clearly, the tradition of celebrating the New Year with Beethoven’s Ninth remains alive and well in Seattle.