Attention must be paid to the set dressing.

Arthur Miller’s The Price is set in an attic, that place where we put all the things we don’t want but with which we cannot part. The characters that populate this purgatory have come to negotiate a price on their history–they are selling the furniture. It’s a perfect setting for an Arthur Miller play and in ACT’s current production (through June 22nd) the set also nears perfection.

The Price is one of those plays in which resentments fester beneath the surface until circumstances force them to break out and someone says “let me tell you what really happened.” The script is solid, and respected, if not of Miller’s finest, but in this production, it’s the clutter of furnishings and props that steal the show. The acting and direction, on the other hand, leave something to be desired.

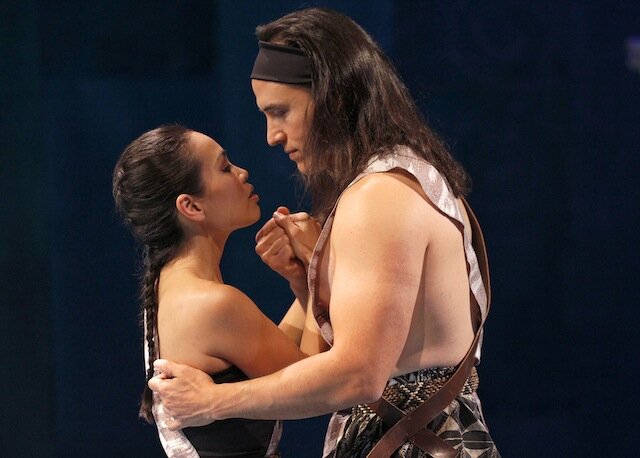

The play centers on Victor (Charles Leggett) the son of a millionaire, who went bankrupt in The Great Depression. Victor’s uncles took over the house, and let their brother live in the attic with all his stuff. Victor dropped out of college and became a cop to support his father. Victor’s brother, Walter, (Peter Lohnes) stayed in school, became a wealthy doctor and sent a little money home to dad.

When our play begins, long after the father’s death, the family is being forced to sell the contents of the attic before the house is demolished. The conflict between the good, happy, and poor Victor and the rich, flawed, and dysfunctional Walter is inevitable and largely predictable, despite some twists and detours in the layers of revelation. However the play belongs to Victor’s wife, Esther, (Anne Allgood) who is the only one who experiences any real change in the play. Unfortunately we don’t see that change occur. We know it happens because the script tells us but the actors show us nothing.

The characters are iconic, almost archetypal: Doctor, Cop, Housewife, (and Furniture Dealer). There is subtlety in the script but this production gives it no support, to say nothing of drawing out further nuance. Rather the complexities of the characters as written are dulled by the actors’ performance. They unfailingly aim for the obvious, retard their pacing, and play emotions instead of actions.

Lohnes is doctor-as-snake-oil-salesman. Yes, Victor says he doesn’t believe Walter but it’s a miracle anyone can, including the audience. He creates the problem of playing a bad actor: the line between playing bad acting and just badly acting is too fine for trifling.

Peter Silbert gives us the furniture dealer, Gregory Solomon as Solomon The Wise, but also Solomon the Borschty shtick-monger. Nonetheless Silbert tends to blow some energy into a play in which the actors rarely seem to be listening to one another.

Leggett employs his paunch and pate to easy effect along with his standard folksy, simple guy accent. While Alyssa Keene is cited as dialect coach she seems to have worked only with Silbert (who still needs some practice). Leggett gets to pull out the stops in Victor’s big emotional moment. It’s good craft and affecting, but that moment feels utterly disconnected from everything around it.

Allgood has the toughest role here. She doesn’t get to indulge in histrionics or interesting character bits and she endures casual misogyny from men who are always telling her to sit down, be quiet, or be more supportive, and calling her “kid”. On top of that her character embodies the dramatic action of the play. Unfortunately we miss that action entirely.

While the arena staging creates its own special challenges Victor Pappas’s direction inevitably found Allgood hunched over protectively at key moments, effectively shutting out the audience. All we could see was that Esther had a view of the world, listened to conversation, and came away with a new view of the world.

So, about that set; Robert Dahlstrom gives us a wonderful NYC skylight-crowned ceiling, high above the stage and a farrago of furnishings, much of it matched to precise descriptions in the set. Also excellent is Brendan Patrick Hogan’s sound design. The music coming out of what appears to be a wind up phonograph, despite its rather electrical whine, is authentic and spot-on.

That nuance and complexity we wanted in the acting—we find it in Alex Berry’s lights and Rose Pederson’s costumes. The costumes in particular demonstrated excellent research and execution in character, and circumstance. Let’s hope future ACT productions will learn something from her.