This is Part Two of MvB’s adventures on the high seas: See “Shipboard Notes” here.

The most pernicious misconception I had about cruising the Caribbean was the fantasy where I spent the whole time flat on my back on a lounge chair on the upper deck, working on a tan, harassing waiters for daiquiris, and making plans for “second lunch” at the buffet.

You can do that, certainly, and cruise lines like to play up the pampering, but if you have an ounce of explorer in you, stopping at a new island each morning will have you up bright and early, ready to hit to the beach pier. There are a staggering amount of things to do each day, just choosing from among shore activities “sanctioned” by the cruise lines. (Here’s my 119-page Royal Caribbean Tour Brochure[pdf].) You just need to find out where the gangway is–it may move around depending upon the pier, and if other ships are in front of you–and head down the pier toward the people holding little signs over their heads.

In theory, your cruise line hosts have vetted these offerings for you, to make sure the vendors are reliable, committed to customer service, and determined to get you back to the ship before it departs. In most cases, we found that true, but my brother still had two tours cancelled on him, one the night before, and one the morning of, which left him suddenly embarking on a walking tour in scuba apparel. More experienced cruisers, we found, were more sanguine about hiring tour guides on arrival and haggling for cheaper prices than listed in the brochure.

On a gray, rainy, mid-eighty-degree morning in Grenada, I went on the Island Seafaris Eco and Snorkel Tour ($84, 2 hours) which took us on a tour of the west coast’s Dragon Bay, Black Bay, Lagoon, and Carenage, with a stop at an underwater sculpture park at Molinere Point. The powerboat was a larger inflatable type you might know from rafting; you sat two abreast on a saddle seat, with a harness, and the boat zoomed about on two huge Mercurys.

Albert held up large laminated posters with maps and pictures of flora and fauna, explaining a little about Grenada’s ecology, and then, with the sun peeking out, herded everyone on a snorkel tour of the sculpture park. The clarity of the water actually gave me a vertigo-induced panic attack, but the certified dive instructor (Howard, I think) driving the boat had plenty of “nervous snorkeler” tricks up his sleeve, and had me paddling back out feeling like a snorkel genius in minutes. (Online, people report knocking as much as $20 off the price of the tour by booking directly, rather than through Royal Caribbean.)

On the way back, we tourists had a quick, informal conference of the trip on how much to tip people for tours. The consensus was a minimum of ten percent, and judging from the response I got, that would, in fact, be the minimum. Fifteen percent at least got a thank you.

Back on land, I headed up the hill to see Fort George, which has a $2 entry fee, and comes with its own set of guides, who will explain the 1983 coup to you, show you bullet holes, and leave you with the impression that wounds have not completely healed yet. I was a little taken aback to learn that this historic fort was in use as both a police station and as an exercise area for the military. The views are well worth the climb, which in the tropically hot and humid weather had me dripping with sweat by the top.

Grenada also has a nutmeg plantation and a rum distillery, as well as more forts. There’s a covered mall at St. Georges’ pier, full of tourist gift shops (nutmeg, honey, nutmeg honey) to take shelter in. One thing I hadn’t fully taken into account about the Caribbean is the frequency of little cloudbursts. You did actually want an umbrella, or at least a lightweight, rainproof windbreaker. Coming from Seattle, the gloom over Grenada that morning had me a little downcast, but Caribbean clouds are not built to last like the Northwest’s. They soon empty themselves or blow by and sunshine returns.

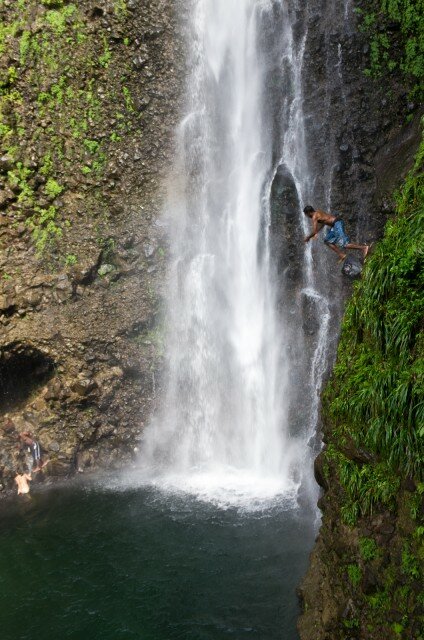

Dominica‘s outings fell into the more outdoorsy camp–it’s being marketed like an outsized nature preserve where you can go scuba diving or hiking to waterfalls or visit sulfur and hot springs. It feels more rural, the gift shops replaced by gift shacks along the side of the road, where locals sell sugar cane, woven goods, carvings, limes. Here I was driven up into the Laudat mountain range, in preparation for the Middleham Falls Hike ($44, 4 hours). They were serious about it being “strenuous,” I learned, and “rugged,” and I was glad I’d brought some lightweight hiking shoes, as there were plenty of ankle-twisting opportunities.

My guide was Peter Green, Bushman, of Bushman Tours, whom everyone including me recommends enthusiastically. On the way up, he rattled off facts and figures, CIA Factbook-style, about the flora and fauna; on the hike in, he stopped us to admire flowers, a huge cricket, and hanging vines that you could swing from. Middleham Falls pour into a clear pool that you rock-scramble down to for a swim, since you’re likely red-faced from the climb. On the drive back, we stopped at a hotel veranda for some rum punch, and I realized I should have brought something to eat on this trip. A hurried drive-thru visit to the Botanical Gardens was a little frustrating; I would have preferred getting out to stroll through it.

If there’s a drawback to Dominica, it’s that most of its attractions are the kind that tire you out by mid-afternoon, so you may find yourself heading back to the ship early, to put your feet up for a bit.

There’s no bait-and-switch to the Scenic Antigua and Beach tour ($59, 4.5 hours): For one thing, Antigua is reputed to have 365 separate beaches, so you’d hardly have seen the island if you didn’t stop in at one. For another, it’s incredibly scenic. Shirley Heights gives you achingly beautiful postcard views of Falmouth and English Harbour, and perhaps more close-up glimpses of mongoose, which, introduced in a failed attempt to kill sugar-cane robbing rats, have taken over a number of Caribbean islands.

Then you travel down to Nelson’s Dockyard, where you feel like you’re on a pirate movie set (again, enjoy some rum punch). You’re in a small coach for a good deal of the time, trying to take in the distance between tiny, hurricane-battered shacks inland and the yachts congregating the harbor.

Sometime on your trip it’s guaranteed that you will balk at the return to the ship, and for me, it was upon my arrival at a white, sandy Antiguan beach, where I swam, sunned, drank coconut milk through a straw, and feasted on mini-pineapples, sliced bite-size by machete. It was the quickest 90 minutes of my life.

Bustling little St. John offers the usual shopping opportunities, but walk up the hill a bit to the cathedral, too–it’s worth it.

I was looking forward to St. Croix all week, because I had reserved space on a Coastal Bike Tour ($69, 3 hours), and I wasn’t disappointed. It was 12 miles, round-trip, over mostly flat but potholed roads. We started from Freedom City Cycles‘ shop downtown with a mini-tour of Frederiksted (aka Freedom City), and then biked out to an old sugar plantation (once worked by slaves kept by the Danish) and to the beach.

Our guide Troy filled us in on island history and life in a U.S. Territory (you’re spared voting in Presidential elections, but you elect a governor every four years, and there’s a 15-senator legislature), making it an informatively scenic bike ride.

In the afternoon, we arranged a taxi trip on our own to the Cruzan Rum distillery, where we learned that Cruzan Rum is bottled, in fact, in Florida. You still get to sample some, in a picturesque setting, but if I were to do it all over again, I’d rent a bike and set off somewhere else. Another historic town is Christiansted, and there’s also the chance to visit the 200-acre Creque Dam Farm, the home of the Virgin Islands Sustainable Farm Institute.

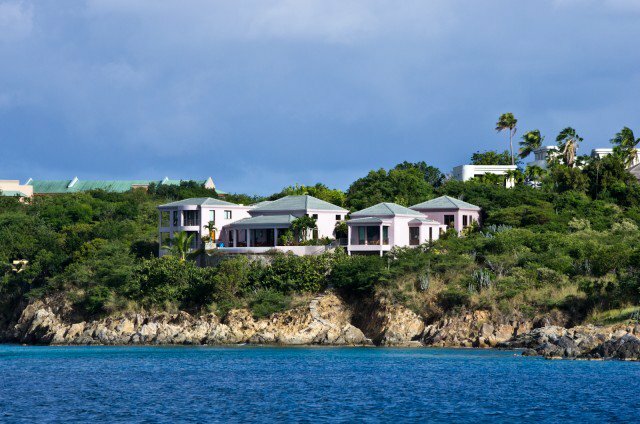

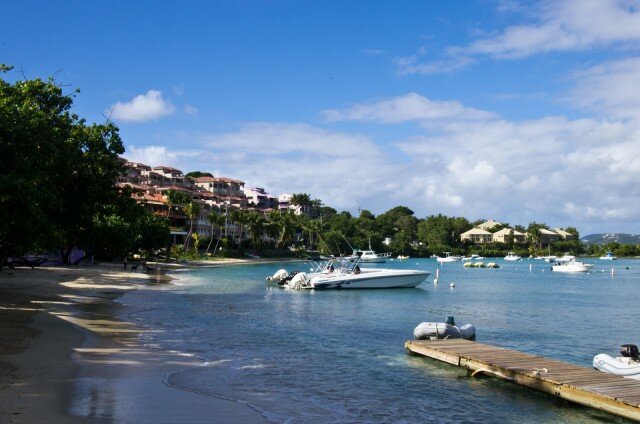

Finally, there was St. Thomas, which I left to go to St. John by ferry “on my own” ($34, 4 hours, 2 hours on the ferry). You get a narrated ferry ride, pointing out the houses of the rich and famous that dot the hillsides, and are dropped off at the impossibly tiny, quaint, and adorable Cruz Bay, which reminded me of what would happen if you transplanted Bainbridge Island to the Caribbean: There are two clusters of little boutiques, a picturesque harbor, and hiking trails that take you out to perfect Caribbean beaches. You actually want more than two hours, if you can swing it. You could easily spend your full day there, dividing your time between shopping for swimming apparel and putting it to good use.

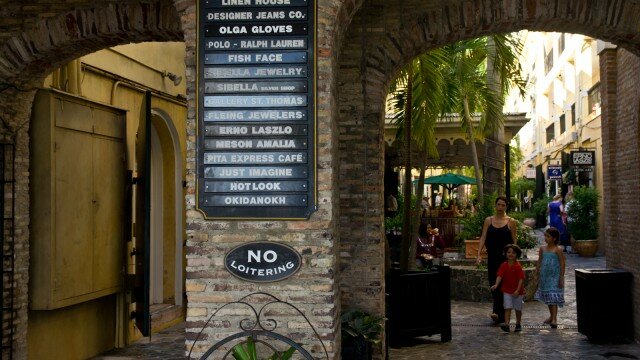

St. Thomas is the Caribbean island for people who don’t want to compromise on their Caribbean island experience. You can snorkel at Buck Island, hit a number of beaches, visit pirate castle attractions, or spend your entire time shopping in huge modern mall-villages or in the warren of shops in the historic downtown area, where I feel sure piracy of a kind lives on still.

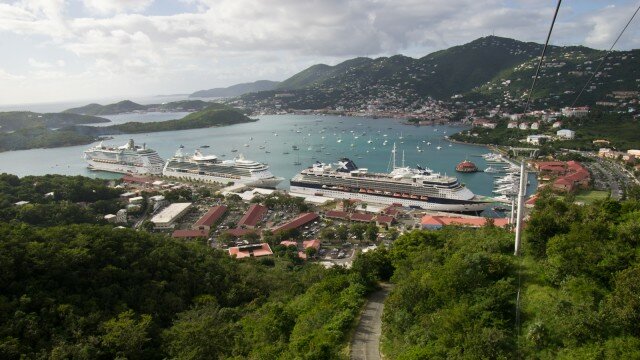

There’s a gondola that will take you up for a birds-eye view overlooking Charlotte Amelie–it’s just 7-minutes each way–and, yes, you can get a rum concoction at the top. Many people love St. Thomas for it’s all-in-one-ness, but it’s also the home of such banalities as traffic jams, and by the end of the afternoon I yearned for the wave-slapping peacefulness of my Antiguan beach.

All this touring around adds to the cost of your cruise, of course, but it’s eye-opening often: You can easily avoid getting shuttled around in buses, emerging only at what seems like a series of T-shirt stands. Hiking, biking, and boating allow you to get different kinds of views of the islands you visit, and how people live there. (I don’t want to disparage shuttle buses–they help cover a lot of ground, but it does feel like traveling in a cocoon if that’s all you do.) Then after a full day ashore, you can retreat to the pool or lounge, sipping that chilled Stella Artois with a keen satisfaction, often having made some new friends along the way.