“Council Members to Mayor: Slow Down on Nickelsville,” goes the Publicola headline from two years ago. Mayor McGinn, in his Ready-fire-aim way, had suggested relocating Nickelsville, the nomadic tent city of 50 to 150 souls, to a SoDo industrial site, and the Council was flabbergasted at the breach of Seattle process and Council protocol.

Anyway, was the site safe? Wasn’t the proximity to the freeway a problem? You couldn’t have a group of homeless squatters, currently living anywhere they could, living just anywhere.

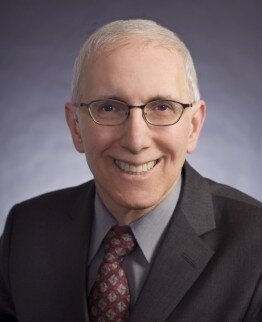

“It may be possible to move forward and meet the needs of homeless individuals with greater speed by implementing alternatives other than the Mayor’s plan,” wrote the Council’s Richard Conlin, in a blog post six months later, concluding: “Let’s not make the mistake of thinking that we can solve issues around homelessness without putting in the energy to figure out what really works.”

“I don’t think we should accept the idea that people are doomed to be homeless and live in tents,” Conlin had told Publicola in November 2010. In October 2011, the Council passed legislation making it easier for religious groups to host tent cities for longer periods of time.

Two years on, Nickelsville, left to its own devices, is flooded, again. “City crews delivered cinder blocks to Nickelsville last week to help with the rat problem,” begins a KING 5 story on the encampment’s flooding by this week’s rains. Mayor McGinn still wants the campers indoors, out of the weather. (Seattle’s City Hall has shelter space on Fourth Avenue between James and Cherry streets–they have capacity for 75 people.)

The Council’s Nick Licata told KING 5 that he’d like to see the Council allocate special monies to provide actual living arrangements (emergency shelters operating, typically, on a night-by-night basis that puts people back out on the street during the day). But, in any event, the camp now represents a health emergency, and the Council’s dithering over whether to acknowledge its existence at 7116 W. Marginal Way SW can’t continue.

Waiting until the City’s actions are dictated by emergency may strike you as incompetent, even negligent. It reveals the camp’s “self-managed eco-village” descriptor as a bitter fiction, as well as the Council’s utter inability to make an executive decision on a matter that has its own timeline. Relocation of the camp’s inhabitants is a necessity. But I wish very much that the City Council could be relocated to Nickelsville until they can decide on a course of action that removes any excuse for tent cities in the first place.