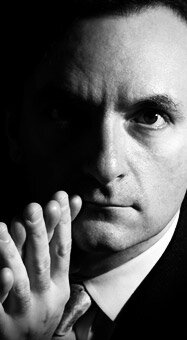

Joshua Roman needs no introduction to Seattle, where he has been the fair-haired darling of classical groupies ever since his appointment as principal cellist for the Seattle Symphony in 2006, a two-year stint which he left to pursue a varied solo career.

However, his appeal to Seattleites, not to mention his fine playing and eclectic musical ideas, inspired Town Hall to engage him to spearhead a new series called TownMusic in 2007.

Now beginning its sixth season, the series of five concerts ranges from the wacky (A Little Nightmare Music, this November) to the intellectually adventurous (violinist Jennifer Koh’s exploration of Bach, his influence on and connection to composers in all genres, next February), to the purely classical as in the opening performance last Tuesday. Roman performs in three of them.

For this concert, Roman, pianist Victor Santiago Asuncion, and violinist Dale Barltrop performed trios by Beethoven and Schubert as well as a recent work by Dan Visconti, a composer whose work Roman has brought here before.

From the first notes of the Beethoven, it was clear that this threesome is of the caliber we’ve come to expect in the UW Series at Meany Hall or at the Seattle Chamber Music Festival. Moreover, Town Hall has the intimacy for chamber music that the size of Meany Theater obviates, and the warm acoustics support the performers as they don’t at Nordstrom Recital Hall.

Barltrop is beginning his fourth season as concertmaster of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, and met Roman at the Cleveland Institute of Music where both were studying. Both have been avid players of chamber music, and Barltrop and Asuncion both studied at the University of Maryland.

They are not listed in the program as a named trio. But having heard them, I can hope that they decide to perform together on a regular basis. This concert was part of a short concert tour which began in Memphis and from here headed to Vancouver and then goes to Australia.

Their Beethoven, the early Trio in B-Flat Minor, was a joy. First noticed was Asuncion’s playing, his runs so clean, so light, so expressive, his phrasing so beautifully shaped. But Barltrop’s and Roman’s playing was equally sensitive, all three of them building to climaxes, ratcheting back to sudden softer sections, full of verve and attack but without aggression in an eloquence which held and absorbed the listener.

Their Schubert, the Trio in E-Flat Major, combined thoughtful undercurrents with bubbling charm, somber at one moment, full of excitement here, lightheartedness there. At all times the three played as with one mind, always balanced so that no instrument overwhelmed the others but came to the fore at the appropriate moments.

Visconti’s Lonesome Road, in its Seattle premiere, is an 18-minute work in seven short movements which purports to portray that American vacation standby, the crosscountry roadtrip. Apparently the movements can be played in any order, and for this trip it seemed they were driving in circles. I heard, I thought, something from Tenessee, down to New Orleans with more than a hint of jazz, out to Kansas with one of that state’s huge summer storms, and back to a bit of Kentucky bluegrass, always with the feel of cars whizzing by and fading in the distance: A well-designed, amusing work easy to hear and never becoming boring.

I’d go with keen interest to hear any of these performers again, separately or together as a trio. The audience, a good size for any concert so early in the concert season, seemed to feel likewise, judging by its response.