The formerly-staid genre of documentary filmmaking has emerged from its dry talking-head ghetto in the last decade, and you can partially thank Alex Gibney for that. Gibney’s non-fiction features crackle with the kind of energy and storytelling techniques normally ascribed to fiction films, whether he’s exploring the lives of a troubled genius in Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, or laying out the labyrinth of corruptive hubris threading through Wall Street in Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room and Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer.

The formerly-staid genre of documentary filmmaking has emerged from its dry talking-head ghetto in the last decade, and you can partially thank Alex Gibney for that. Gibney’s non-fiction features crackle with the kind of energy and storytelling techniques normally ascribed to fiction films, whether he’s exploring the lives of a troubled genius in Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, or laying out the labyrinth of corruptive hubris threading through Wall Street in Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room and Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Eliot Spitzer.

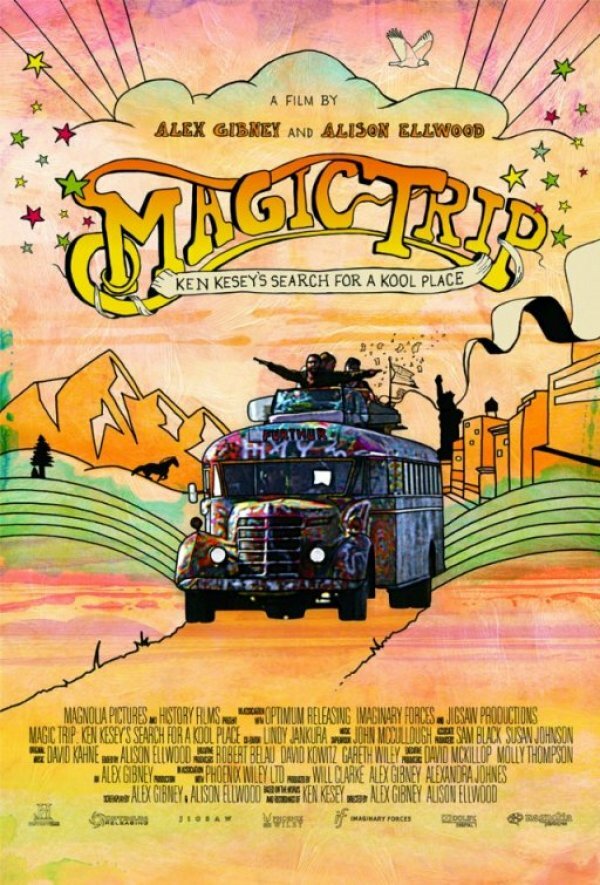

Magic Trip: Ken Kesey’s Search for a Kool Place (screening for SIFF at the Egyptian at 3:15 p.m.) chronicles the infamous, LSD-fueled cross-country bus tour undertaken by author Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters in 1964, winnowing down some 40 hours of the Pranksters’ 16mm footage to a little under two hours.

On the face of it, this latest effort sounds like a nostalgic detour from the hard-hitting work that’s made Gibney’s reputation. But he and co-director Alison Ellwood combine the footage with spoken accounts from the Pranksters and impeccably-executed re-enactment sequences to create a wholly-immersive road movie; one where the viewer stands alongside a fascinating cast of characters at ground zero of the 1960’s American Counterculture explosion. True to form, Gibney and Ellwood subtly show the powder burns that accompany that dazzling flash, too. Gibney sat down with me to offer some choice insights on the nuts and bolts of his new film, as well as some of the driving forces behind his overall body of work.

How did the project begin for you? Was this something you’d been working on for a long time, or did it just drop into you lap?

Well, Alison and I have been working on it for a long time. It was one that we spotted when we were going out to Sundance for Enron. And I just saw an article in The New Yorker, by Robert Stone, who had been on the bus briefly. He had mentioned in that article that there were forty hours of 16mm film; and I thought, “Wow, wouldn’t that be great….” The subject was interesting, but if you’re making a movie, there’s got to be the materials to make it with. So I thought, the idea of having that much footage from that trip; that’d be something.

What was the process like, paring down that forty hours of footage into a workable feature film?

Well, it was more, almost, than just paring down. First, we had to put it back together and then pare it down. The footage really needed to be restored. It was originally shot in 16mm reversal, which meant–like slide film–you could watch it. The bad part about that was: That meant they could project it. So it had developed a lot of scratches.

They [The Merry Pranksters] tried to cut it themselves. Unfortunately they were using hot splicers. A hot splicer means you actually lose a frame every time you make an edit. So, by the time we got the film, it was badly beaten-up. We got a grant from the Film Foundation, which was founded by Martin Scorsese and A & E. The Film Foundation restored the film, and A & E restored the audio. We went in and slowly but surely tried to put the pieces together. I have to give a lot of credit on that to my co-director Alison Ellwood, who kind of found a style for the film by just working with the material. It was shot in a way that was pretty chaotic [laughs]. They didn’t bring a cameraman or camerawoman with them. They thought, “Well, we can just do this ourselves.” Well, that’s not something you can just pick up.

I know you’ve worked with Alison in the past a lot as your editor. I was wondering about her role on this film.

On this film, she was very much determining the style by going in and searching through that footage and finding a way to work with it; in such a way, so that it could be told coherently from frame to frame, and also from scene to scene. So it was very much about setting the style.

You could almost see this movie as a bit of a continuation of your exploration of counterculture figures that started with Gonzo. Kesey was kind of a well-adjusted guy–he married his junior high sweetheart, settled down on a farm–so he wasn’t quite the grandiose figure that Hunter S. Thompson was. Did that present any narrative challenges for you?

I don’t think so. I think that, in his way, just like Hunter, Kesey was a tremendously charismatic figure. I think the star of the [film] is Kesey. He’s different than Hunter, and did end up inhabiting, in some ways, this very traditional Western family…. He was a traditional Western family man: rugged, individualistic; but not so much a ‘wacky counterculture character’ in some ways–even though, in some ways, he was that, also. I never thought of him as not being as wild or as interesting as Hunter. He was different; in some ways, much better adjusted than Hunter, but in some ways more anarchic and wild in terms of his ideas. He’s like the quarterback of the football team: He uses that metaphor in the movie, actually. He said, “I don’t want to be the ball. I want to be the quarterback.”

Most of your documentaries have been more investigative and hard-hitting. People on the outside who haven’t seen Magic Trip may look at the subject matter and say, “Oh, this is just going to be a nostalgia trip. This great documentarian is just coasting,” How would you respond to that kind of initial perception?

Well, it sure wasn’t coasting [laughs]. This one took six years, so it was hard labor. We wanted it to be an immersion trip. But I think with the benefit of hindsight, we can include materials in the story that reflect the more contradictory view of the [decade of the] sixties. There’s something wonderful about it, there’s something sort of wide-eyed and idealistic about it, and free about it. But there’s something that’s also fraught; you can feel the dark undercurrents to come. And in the search for freedom you can see the kind of ruddering against human nature that is ultimately going to cost everybody, big-time. So, there’s a lot in there. And there’s a lot of self-indulgent bullshit as well, really….

One of the things that I like about the documentary is that you present both of those aspects…

Right.

You see fucked-up people acting fucked-up; then you see people–oftentimes, those same people–really, truly exploring themselves and the world around them…

Yeah, the idea of them as explorers is a good one. Kesey was a big Melville nut; so the idea of these people on the high seas in some way…that, I think, registers. But explorers generally make some pretty stupid mistakes. When that territory–that trail–hasn’t been blazed before, you’re going to bump into a lot of trees, to mix our land and sea metaphors. That was important to me. I think one of the key characters in the film is Jane; this woman who’s pregnant on the trip. A lot of the time she’s very tired. The trip itself is exhausting, and you can feel that exhaustion at times in the movie. But she has this very sardonic sensibility, and she’s always showing the kind of self-indulgence that these characters inhabit.

A lot of these folks passed away long before the completion of the movie. Did you have a lot of direct interaction with the Merry Pranksters?

Sure…we started out this project in a much more traditional way. We filmed interviews with people who would look back on the events that they’d taken part in and reflect on them. We tried that a little bit, and were disappointed with the results. We found that some of the stories had been rehearsed over and over again; in some ways the Pranksters were bored with telling them. There was also, inevitably, a sense of looking back; and kind of a creeping nostalgia, even in those people who were critical about some of the events. There was kind of a reinventing of some of [those events].

To me, one of the appeals of doing the film was that footage, because it was there. You were in the moment. And then we found these other audio tapes of the Pranksters, not too long after the trip, reflecting on it. That somehow seemed like a much better way in.

It lends an immediacy to the project that your standard-issue talking head documentary…

…would not. It would constantly be taking you out, then putting you back in. There’s something about, “You’re along for the ride.” At times, that ride gets very tiring, as it must have been for them. And at times, it’s exhilarating. Because you feel like, Whoa, I’m here.

We’ve had four or five decades of the media enforcing this idea of the counterculture movement as all long-haired, unwashed freaks in wild clothes and love beads. It’s really interesting to see how ‘normal’–straight, even–the Pranksters looked.

Yeah, they look like they’re straight out of the fraternities and sororities in Animal House; consciously. Kesey had this thing about the red, white, and blue. They’re wearing these red, white, and blue-striped shirts.Their hair is all cut very close. And they’re all gorgeous-looking, I must say. Very handsome, very lovely people.

You struck it lucky with some very beautiful documentary subjects.

Yeah, wow [laughs]! They just exude a kind of sensuality and youth that’s tremendous. Even Neal Cassady, the famous hero of On the Road, was older than the rest of them were, but still, most of the time he’s got his shirt off; he’s still ripped and very handsome.

He’s like this great character actor at the front, driving the bus…

Yeah, he’s like something out of a Budd Boetticher western.

Were there any bits left out of the final cut of the movie that you would’ve left in if you’d had, say, ten more minutes of screen time to play with?

Oh, sure! There was this wonderful sequence of them going down to Tijuana, Mexico, watching a bullfight. It’s just a beautiful, beautiful sequence. It was also not that-much-used by them. They had tried to make this movie many times. And as a result, it was very pretty to look at. I’ll give them credit on one thing: This was film, so you never know what you’re gonna get until you put the film into the lab. One thing they had down was their exposure. You would’ve had to do that with a light meter, and that, they had down. Most of the footage was very well-exposed. Boy, that Mexico stuff would’ve been great to include.

Did your perception of any member of this cast of characters change appreciably over the course of completing the film?

I think I saw Cassady in a rather different light. I both appreciated his greatness and his charisma, but also his complete nuttiness. And I think in some ways, a kind of speedy desperation. There’s a lot about what Jane says in the film that’s correct. He was a kind of action hero for very famous writers and poets, but he couldn’t create that notion himself. It must’ve been a weird existence for him, where he almost felt like a creation of other people. And I think that opened my eyes.

Have you gotten any feedback from the Pranksters or their families?

Yes. We showed it in Eugene, which was a magnificent night, at a film festival run by Richard Herskovitz there. It was great. A lot of the surviving Pranksters showed up. Mountain Girl was there. The theater was packed; there was a lot of psychedelic memorabilia [laughs]. And they loved it. George Walker said, “This is the film we set out to make,” and nothing could be a higher compliment. Alison and I, I can tell you, were terrified, because we had these big [dramatized] drug sequences in it. What are these veteran drug explorers going to think of those? But they loved them, so we felt pretty good about it.

One of the hallmarks of your style is that you don’t make dry documentaries. There’s a real cinematic-quality narrative driving them. It seems to point to your background editing trailers and working on fiction features…

I think that’s right. Let’s face it: There are a lot of talking heads in my films. But they’re usually surrounded by a lot of other stuff. I think a lot about style when I make a movie. I don’t think there’s an individualistic style for me, but I think a lot about how each film should have a different style according to the subject. This one, Magic Trip, was a very different kind of thing. Client 9 has a much more classical look: It’s meant to be sort of a sophisticated mystery thriller. And it was shot like that. [Magic Trip] is wildly different. It’s kind of an archival cinema-verite project.

You won an Oscar for Taxi to the Dark Side, and made documentaries that have left a strong impression on the public consciousness. Is it easier for you to get projects off the ground now? Do you have total freedom in terms of choosing subjects?

I wouldn’t say total freedom; and choosing subjects usually doesn’t work that way. To be honest, most of my films–not all, but most–are films that are brought to me, and financiers tend to like that more. “This is a film I’d like to do. How would you do it?” Then I have to think, well, is this something that would be interesting to me? And if it is, I take the gig. It’s usually easier to get films made that way.

What would be an example of one closer to your heart, as opposed to one that was inspired or imposed by an outside source?

Well, Enron was my idea, but one of the films that’s closest to my heart is Taxi to the Dark Side, which someone suggested that I do. It’s hard to tell: Client 9 was one that was brought to me, and I had a ball making it. I felt like I was at the top of my game with that, if I may say so myself [laughs]…in terms of the storytelling. It’s a complicated story. For me, at least, it doesn’t work that […] the only [films] I care about were the ones I thought of first. Sometimes, you take a journey. Magic Trip would be a classic example. That is one that, when Alison and I were reading that article, we thought that it’d make a great movie. But it didn’t turn out to be the movie that we set out to make.

I would almost liken your work to that of Robert Wise, a director who made a lot of great, varied films; yet there was no overt, giant hand-stamp on his work like, say, Alfred Hitchcock.

That’s fair. I think that’s my thing; just to find a way for form to marry content. Each film gets reinvented according to the story you’re telling. The other thing I learned from doing the fiction projects was not only a sense of paying attention to visual style, but also the importance of narrative. I think that’s been the freeing thing in the last ten or fifteen years of documentary filmmaking. It’s the willingness to make documentaries more than reports. They’re stories, like good non-fiction books, really.