Contemporary 4, at Pacific Northwest Ballet through March 27, concludes with the PNB premiere of Alexei Ratmansky’s Concerto DSCH. The phrase, “From Russia, with love,” takes on a new context here.

If you follow dance, you’ve heard about Ratmansky, the former Bolshoi dancer who “grew up” to become the former Bolshoi artistic director, now with American Ballet Theater. Concerto DSCH, though, he created for New York City Ballet, where, the New York Times will tell you, it was a “smash hit.”

It went over big in Seattle on opening night, bookended on this program with Mark Morris’s Pacific, which is the opener. From an early age, Ratmansky told PNB director Peter Boal–who was doing a more-than-credible Dick Cavett impression during a pre-run interview with Ratmansky earlier in the week–he was in love with Shostakovich. When you see Concerto DSCH (the “DSCH” is a musical motif), the depth of that affinity is apparent from the first seconds. You will be enraptured.

It feels right to pair Ratmansky with Morris because although you would not mistake one for the other (unless you freeze-framed on one slumped-over pose that appears in both works), their dances share a remarkable, rigorous charm. If Concerto DSCH is described as one of Ratmansky’s “abstract” works, you should know that it’s not Mercer Cunningham abstraction. It reminds me more of what Brian Wilson was trying to accomplish with Pet Sounds‘ emotional tone poems–a distillation of feeling. Ratmansky is aided in this by the wonderful performance coming from the pit, led by Allan Dameron and featuring Duane Hulbert on piano.

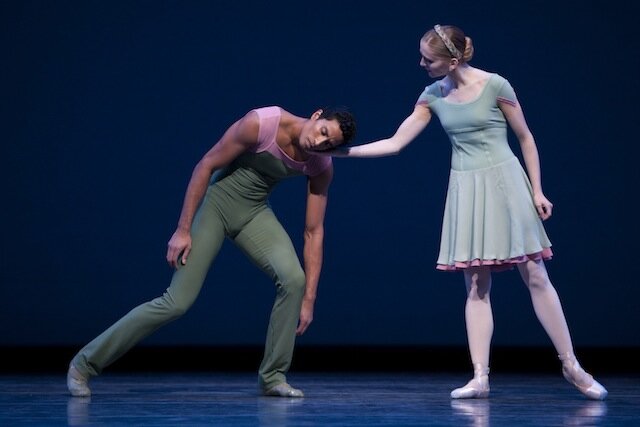

It opens with dancers stepping out of a ring of other dancers, as if a rebirth is taking place, and except for the sorrowful, more contemplative second movement (in which a group casts out a member, recalling Shostakovich’s ins and outs with Party society), the stage is filled with vibrant motion, with dancers actually dancing–some hopping–as if from the sheer joy of it (Carrie Imler was all wide smiles and stepping). If it’s equally a joy to watch, it’s not because it’s easy. Ratmansky shuttles the dancers all over the stage in rings within rings, or diagonal flights, and gives Batkurel Bold and Seth Orza a series of entrechats, spins, and leaps with weight shifts that evolve in mid-air so that they land on a different foot than you expected, facing a different direction. Karel Cruz and Carla Körbes are a playful, winsome couple who meet and test each other out with a flirtatious shyness that contrasts with the work’s overall neo-Realist, boldly-we-face-the-future aesthetic (Holly Hynes’s beautiful costumes). That’s the more serious question repeated at the heart of the work, as a dancer is pushed to the floor, who the “we” is and isn’t, and how to repair the circle.

I’m just going to say it, if you like your male dancers bare-chested and ripped, the first half of the program is unmissable. Perhaps because it was opening night, the work began a little stiffly, but why quibble about that when you get to see Ariana Lallone and Lucien Postlewaite in that duet pictured above, and Olivier Wevers partnered with Carla Körbes.

The dancers are in flowing shades of blue, green, and a reddish-orange (Martin Pakledinaz’ designs) and while you’re used to that on women, the way it recasts and opens up the men’s movement is striking. The fluidity of below-the-waist movement is countered by gestural series in the arms and hands, which, people will tell you, evokes the “Kathak style of southern India.” I’ve never managed to make narrative sense of this work, but I’ve never felt that I needed to, it’s so purely evocative, and of a piece with Lou Harrison’s music. If you surrender to it, you’ll find yourself transported by the smallest thing–a just-missed chance for hands to meet one moment that finds its resolution in hands clasped a little later.

Place a Chill is a world premiere from choreographer Marco Goecke, and it’s one of the more startling, sui generis works I’ve seen, beginning with the Mark Zappone costumes that have bunches of flowers protruding from the dancers’ shins. To Camille Saint-Saëns’ Cello Concerto No. 1 (there’s a story to that cello music, performed by Page Smith), the dancers scuttle about the stage by petit pas, like sea creatures moving with the tides.

Their arms are in constant, hyperfast movement that appears more digital than analog, as if the dancers’ hands were simply appearing in different positions, rather than moving there. It actually becomes taxing to watch, because of the speed and extraordinary precision of the movement.

The movements, although alien at first glance (to ballet, in any event), have a definite connection to the music. It’s just that instead of dancing out the plangent melody of the cello, the dancers are vibrating to microtones and the frictions of the bow on strings, or even bending each other into imitations of the celloist’s contortions around the instrument. It may be a dark, eerie underworld, seemingly far from the cool serenity of the music, but it shows you artistry’s daimonic face, where the music arises from.

The Piano Dance, from Paul Gibson, in this company, felt like an entr’acte that was a little too long. Put another way, it was the maraschino cherry of the evening–some people really go for maschino cherries, but I can usually just handle the one. That’s not to fault the pianist (Christina Siemens), who had the following on her plate:

Frederic Chopin (Prelude, Op. 28, No. 4, 1835-1839), John Cage (Opening Dance for Sue Laub, c. 1940), Gyorgy Ligeti (II, III, IV, VI, and X from Musica Ricercata, 1951–1953), Bela Bartok (“Chromatic Invention” and “Ostinato” from Mikrokosmos, Sz. 107, BB 105, 1931-1939), and Alberto Ginastera (Suite de Danzas Criollas, Op. 15. No. 1, 1946)

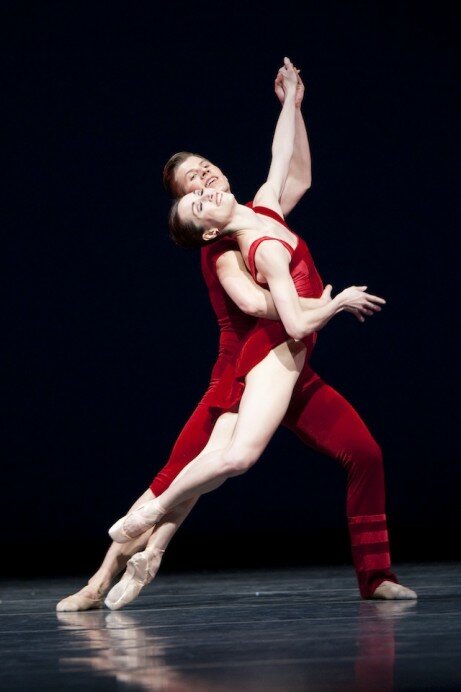

There were moments of invention–Lesley Rausch attaching herself to Seth Orza’s midsection (Orza was dancing for Jeffrey Stanton) like an urchin, then slowly opening her arms and legs like pincers–but more frequently what I saw were ballet études, pretty enough, but sometimes sentimentally flip. The dances themselves were outshone by Mark Zappone’s lurid red costumes and the use of red backdrops of shifting height (lighting was by Lisa J. Pinkham). I could tell that a portion of audience was sighing comfortably and thinking, Ah, this is ballet, but then they had yet to see Concerto DSCH.