Last weekend’s closure of the I-5 on- and off-ramps at Mercer Street caught a good deal of Seattle Opera patrons, trying to head to McCaw Hall on Seattle Center campus, off-guard, even if they weren’t taking Mercer at all — the closure shifted traffic to the already heavily-used Denny Street, slowing it down as well. Riders on the perennially-late and packed 8 bus that runs cross-town on Denny were caught up in the congestion, too.

The Opera, which had alerted its patrons in advance, still held the curtain for a few minutes because of the traffic jam. With work on Mercer ongoing, they warn that at this summer’s performances of the Ring — where due to Wagnerian length they can’t afford a late start — it will be even more critical that opera-goers plan to arrive with plenty of time to spare.

The news from Seattle’s department of transportation is to expect these kind of delays, over the next two years; “a trip near Seattle Center will take five or 10 minutes longer,” is how Mike Lindblom puts it in the Seattle Times. That seems likely to be an average, with busy nights at the Center tying up traffic for longer.

If you need to travel Mercer, you likely want to subscribe to email alerts from here on out, as Mercer Corridor project construction brings new closures and lane restrictions.

As of today through Friday, May 17, Westbound Mercer Street (and Broad Street) will narrow to a single lane from Westlake Avenue North to Harrison Street. Tomorrow, Friday, eastbound Mercer will be a single lane from just west of Dexter and 9th from about 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. For the next three weeks, northbound 9th Avenue North, from just south of Aloha to 8th, will have a single northbound lane.

Then, the weekend of May 17 to 20, SR 99 will close between Valley Street and the southern end of the Battery Street Tunnel, while Mercer Street will be fully closed to traffic between Fifth Avenue North and Dexter Avenue North. SR 99 traffic will be directed to I-5 at the bottleneck, so expect slow going there, while Mercer traffic will detour over to Denny from 5th to Dexter, and back to Mercer.

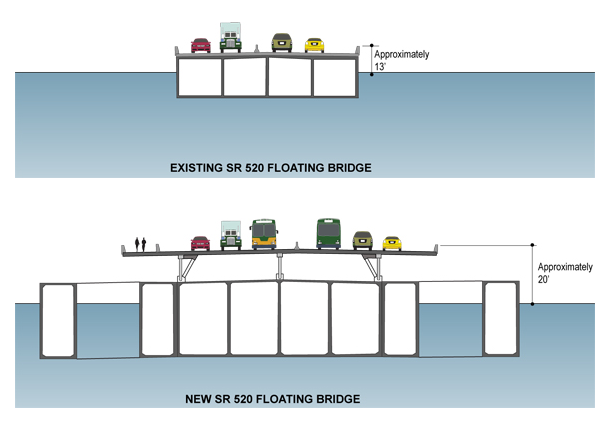

The weekend closure is to help SDOT prepare for the demolition of the eastern half of the SR 99 bridge over Mercer; once that’s out of the way, crews can work on widening Mercer between 5th and Dexter, to allow two-way traffic. That part of the Mercer Corridor project is expected to take until mid-2015. After the weekend closure, says SDOT:

- Mercer Street will be reduced to two eastbound lanes between Fourth Avenue N and Ninth Avenue N.

- SR 99 traffic will be shifted to the west side of the roadway between Valley and Harrison streets. Two lanes will remain open in each direction.

- The northbound SR 99 off-ramp to Mercer Street will be permanently closed. A new signalized intersection at Republican Street and Dexter Avenue N will be available for northbound SR 99 traffic to reach South Lake Union.

- Local access to Taylor Avenue N via Mercer Street will be maintained.

- Sidewalks on Mercer Street will be impacted during this work. The sidewalk on the north side of Mercer Street will be closed between Fifth Avenue N and Dexter Avenue N. The sidewalk on the south side will remain open to pedestrian traffic.

To help with congestion, Broad Street will reopen to eastbound traffic, and traffic southbound on 5th will be able to turn left onto Harrison to get to eastbound Broad Street.

When finished, motorists will be able to take the Mercer Street exit from I-5 and drive directly to Seattle Center, which should be an improvement. (You could already drive eastbound from the Center to I-5 on Mercer, so that won’t change much.) Equally important, as South Lake Union develops, is the transformation of Mercer on behalf of pedestrians and bicyclists. Its earlier incarnation hadn’t much room for either, especially where Mercer ducked beneath SR 99.