Completing its 15th season Tuesday night at Nordstrom Recital Hall, Music of Remembrance once again gave its audience music and memories that propel discussion and stay with you long after the performance is over.

Composer Jake Heggie and librettist Gene Scheer, both continuously in demand by major opera companies, important musical organizations and musicians, took time, again, from their busy work schedules to create another work for Music of Remembrance.

In fact, two works.

Their group of songs, Farewell, Auschwitz, explores the enduring legacy of Polish Jew Krystyna Zywulska through the poetry she wrote as a political prisoner in Auschwitz, her Jewish identity unrealized by the Nazis. It’s a continuation of the music drama they premiered with MOR last season, Another Sunrise, on the appalling dilemmas Zywulska faced in her painful struggle to stay alive and make a difference.

But as well as this important premiere, Heggie and Scheer also created a distillation of their first work for MOR in 2007: a song cycle from their music drama For a Look or a Touch, which brought to prominence Nazi persecution of gays though the diary of a young gay man, Manfred Lewin, who was murdered at Auschwitz but whose partner survived.

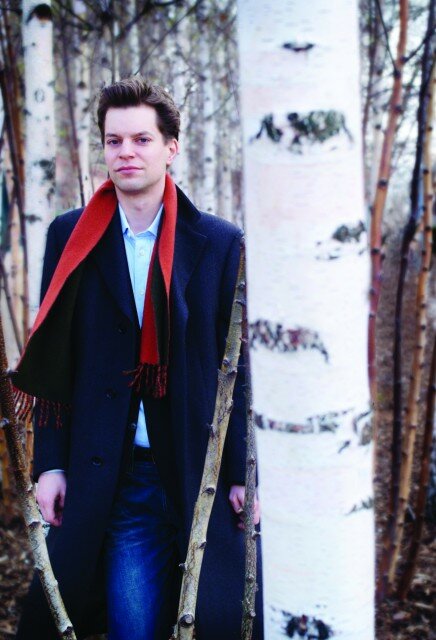

It was the performance of this distillation which left the strongest impression of Tuesday night’s concert. Baritone Morgan Smith, who created the role of the diarist as ghost in 2007, sang the cycle of five songs. A 2000 graduate of Seattle Opera Young Artists Program, he has honed his strong baritone and considerable acting skills to a fine international operatic career, but, like Heggie and Scheer, he has come back to MOR more than once.

With a quintet of flute (Zart Dombourian-Eby), clarinet (Laura DeLuca), violin (Mikhail Shmidt), cello (Walter Gray), and piano (Craig Sheppard), Smith embodied the despair of the Auschwitz present, the memory of freedom, fun and love in prewar Berlin, the yearning and grieving of the now, the witnessing of horror with the incongruity of Nazi musical overlay, and speechless sorrow.

The poignancy of his acting, this tall man with long arms at a music stand, the agony in his big voice, had the audience riveted as he brought to life Scheer’s beautiful lyrics drawn from Lewin’s diary with Heggie’s music. This mirrored the times, including the Weill-like sassiness of 1930s Berlin with a memorable jazzy clarinet solo from DeLuca in “Golden Years,” the celestial, melancholic imagery in “A Hundred Thousand Stars,” and the nightmarish contrasts between savagery and sweet waltz in “The Story of Joe.”

Hearing this performance would alone have made the concert memorable, but the premiere of Farewell, Auschwitz after intermission added more.

Zywulska, who never previously had written lyrics, wrote them to keep herself going in Auschwitz and set them to popular music of the day. They took fire in the camp, and because of them she was given a job in the Effektenkammer, the warehouse where were collected the belongings stripped from new female prisoners before they were gassed. This effectively kept Zywulska alive.

In Farewell, Auschwitz, Scheer took Zywulska’s satiric poems or fragments thereof and made free poetic adaptations, while Heggie, facing the impossiblity of finding the original tunes, created music which might have been of that era, either movie or Weill-like or folk melodies, even adding a bit of Chopin and Liszt. All of it, however, had an indefinable touch of today in harmonies or musical progressions.

Smith was again one of the singers, along with soprano Caitlin Lynch and mezzo soprano Sarah Larsen, also past graduates of Seattle Opera Young Artists Program, while the instrumental quintet included DeLuca, Shmidt, Gray, Sheppard, and Jonathan Green, double bass.

The lyrics are intense, moving portrayals of life in the camp and at the same time songs of resistance, brilliant writing by Scheer from Zywulska’s original words. Heggie’s music is equally brilliant, evocative of the era, descriptive of the words — and at times shocking in its impact, particularly in the final song, also titled “Farewell Auschwitz.” At the end, the three singers gripped hands and stood defiant:

Take off your striped clothes;

Kick off your clogs.

Stand with me.

Hold your shaved head high.

The song of freedom upon our lips

Will never, never die.

I was not the only one in the audience with tears in my eyes.

I would have preferred Lynch and Larsen to pitch their voices a little more softly at times, given that Nordstrom holds only 540 seats rather than 3,000, but that was my only quibble.

Two instrumental works completed the program. Laszlo Weiner’s String Trio—Serenade of 1938 introduced us to a fine work from a composer whose life was cut short in 1944 in Lukov labor camp. It was well played by Shmidt, violist Susan Gulkis Assadi, and cellist Mara Finkelstein, and worth hearing again.

The concert opened with a 1930 violin-and-piano adaptation of a suite from Weill’s The Three Penny Opera, done by a close friend of Weill’s, Stefan Frankel, who eventually became concertmaster of the Metropolitan Opera orchestra. It’s a showy and difficult violin part—shades of Paganini—but the performance sounded as though it was a first rehearsal by pianist (and founder and moving spirit of MOR) Mina Miller and violinist Leonid Keylin. Keylin, an excellent violinist, brought no soul to this. The work didn’t seem to speak to him, so it also didn’t speak to us.