Nothing in Turbulence, the largely improvised movement piece from Keith Hennessy and friends, confronts you with anything like that moment in Crotch (all the Joseph Beuys references…) when he has to sew bystanders (their clothing) to his skin with red thread.

But something else happened during the performance at Velocity Dance Center that was perturbing in its own right.

The “only nonimprovised piece in the show” is the building of a human pyramid, with the performers and volunteer audience members stripped down to underwear or nudity. They have hoods made of a shiny gold cloth on. Given that “Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine” are the first five words in Hennessy’s program note, it would be difficult not to see a reference to Abu Ghraib here.

What kind of reference is wide open, but it was a shock to hear how gleefully the audience responded, cheering and encouraging the participants as knees and elbows wobbled, palms slid. Despite the hoods, despite the evident point being exhausted collapse, the audience (generally speaking) seemed to want to treat it as simply a cheer pyramid, a test of endurance. (Perhaps one or two guards did, too, it occurred to me. Remember when a few pundits compared it to hazing?)

There’s no “right” way to respond to a human pyramid, of course–but this was proof that Hennessy had succeeded, it seemed to me, in getting the audience involved as an improvisational partner. (In Portland, there was a Champagne slip ‘n’ slide that brought hipsters into a playground of excess. So, involved, or complicit.)

He told Culturebot: “People have to enter it poetically or that won’t happen. If they’re just waiting for the content to arrive it won’t happen.” (You get confirmation of that from this upset review, which includes the line, “I am very patient with these things!!”) He’s done what he can.

You wander in to something already happening, a “fake healing” involving dancers laying on hands, setting objects on top of audience members, manipulating their limbs. People are gently invited to join (I turned my person down because I wouldn’t be able to see what was going on), and it’s explained why it’s fake (“There’s nothing wrong with you”) and how it helps people open up a little to what’s going on, even if they’re just watching other people being open.

There’s no need to justify what Hennessy is up to, since getting out of that box is part of the project. (In fact the set is mainly splayed-open cardboard boxes.) Turbulence is supposed to (like the economy isn’t but does) fail. The other ur-text here is Judith Halberstam‘s Queer Art of Failure, which talks about refusing normative values and practices.

Hennessy queers dance, then, your expectations of it (or of performance art) and pursues what looks like a terrible idea, because how can dance be about the economy…and be good? (Coincidentally, you can go see another dance about the economy at Pacific Northwest Ballet, Cinderella. It’s about as normative and representational as things get, to the extent that nothing about the economics that creates penniless serving girls registers.)

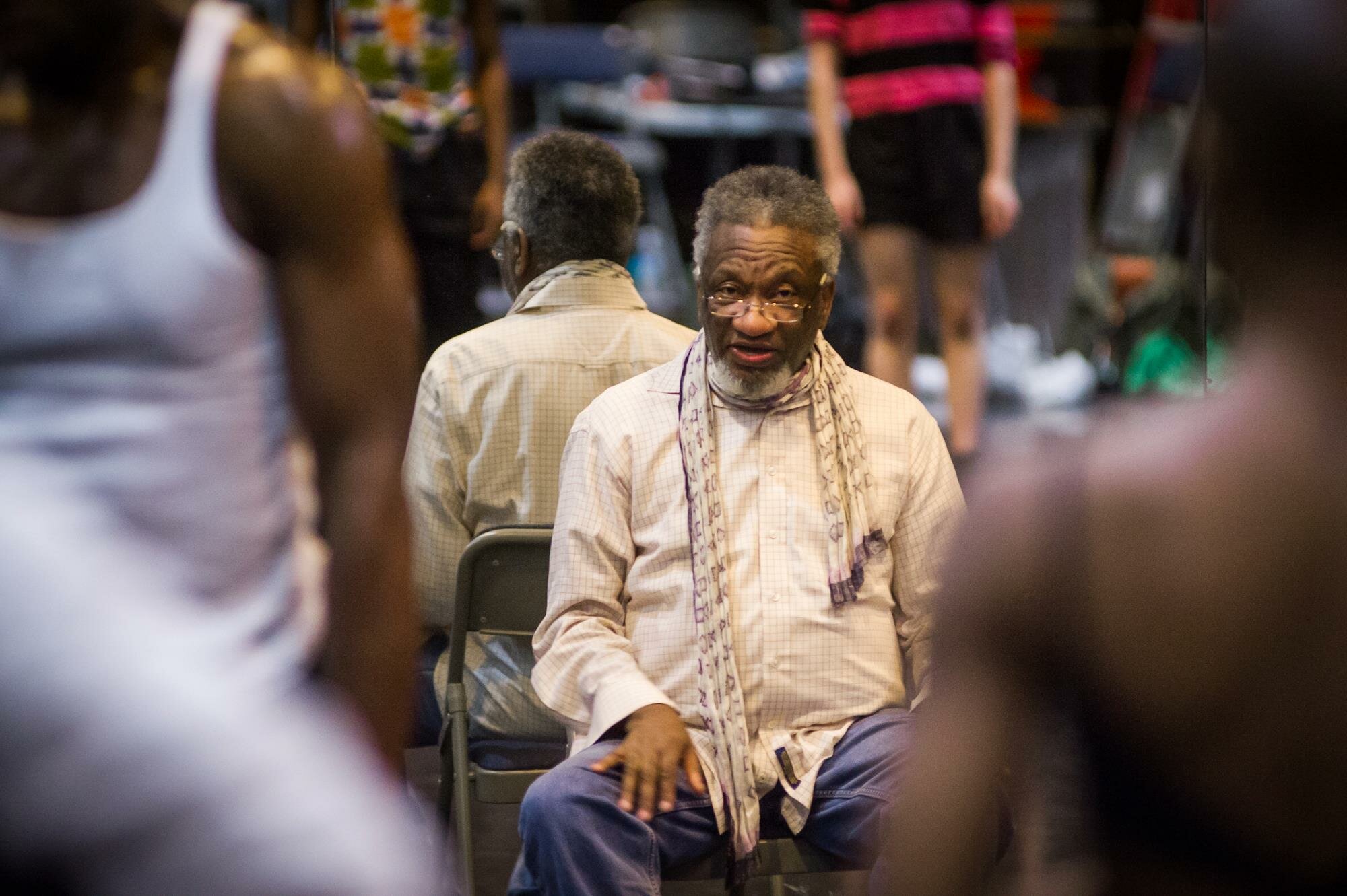

Despite occasional outbursts, Hennessy and his troupe–Julie Phelps, Emily Leap, Laura Arrington, Jesse Hewit, Jorge Rodolfo De Hoyos, Hana Erdman, Gabriel Todd, Ruairí O’Donovan, Empress Jupiter, Jassem Hindi, with special Seattle guests Markeith Wiley and Joan Hanna–largely refuse the prospect of arguing with the economy. What happens is somatic, the experience of the body. There’s a scratched-up, staticky soundtrack, dj’d live, that is more about the feeling of the words than the content.

People pair up, or antagonize each other, or tangle furiously. If two dancers practice linking themselves, their weight counterpoised, a third will jump in. Throughout, the dancers swap clothing, stripping down and dressing back up. A trapeze set becomes the setting for blind, hooded, acrobatic feats–though the climb to the top is always greeted with the question of where to go from there.

Dancers move among the audience members, sometimes shouting out to those on the floor, sometimes having semi-private conversations. A gold sheet is produced, and passed over audience members like they’re playing under the covers. No one is likely to have the same experience: There are too many rings in this circus to attend to all of them. You can pay attention to the dancer screeching and masturbating, or you can look elsewhere.

For somatic poetry on economic collapse, though, it’s hard to beat when Hennessy, sitting on cardboard and talking about bitterness and anger, also reveals that the dancer sitting next to him has peed his underpants, and they’re all sitting in it. So much is contained in this: the stench of homelessness, animal fearfulness, the way this more ignoble (than blood) bodily fluid unites us, contaminates us. If you bother to think back to when thousands of people were losing their jobs weekly, you’ll smell the piss-stink again.

A quote attributed to feminist scholar Peggy Phelan pulls some of these strands together:

Love, despite its toxicity and violence, can bring us closer to the possibility of expressing human tenderness. If one is ambitious enough to want to create a shared history, then one must be willing to risk an impossible dance, one that pivots on a desire to outmuscle exhaustion, a desire alive to our wavering capacities to bestow and receive responses, and an apparently insatiable desire to question these capacities and what motivates and blocks them, repeatedly.

The ending is individual; once the improv list has been completed, you’re invited to stay, come down off the bleachers. Some people formed another human pyramid. Many more joined in a dance party that Hennessy decided to turn into super-slow-motion. A few stood around and talked. A conga line formed.

Turbulence may be meant to fail, but I don’t regret the time I was there, watching it refuse to amount to much, at least by some standards. It was a transient blip, in the greater scheme of things, but it created its own peculiar space while it existed. And if you think of healing in terms of wholeness, its ability to give you back the humanity in a human pyramid, the effervescence of an economic slide (both banished, we all had to pay somehow) is remarkable.