On the Boards‘ presentation of Portland dance company tEEth‘s Make/Believe packs an emotional wallop as its four dancers wrestle with power, voice, and microphones. Angelle Herbert’s choreography, together with Phillip Kraft’s sound design, openly lays claim to the audience from the get-go and doesn’t release its hold for a moment as the dancers struggle to find their literal and figurative voices.

On the Boards‘ presentation of Portland dance company tEEth‘s Make/Believe packs an emotional wallop as its four dancers wrestle with power, voice, and microphones. Angelle Herbert’s choreography, together with Phillip Kraft’s sound design, openly lays claim to the audience from the get-go and doesn’t release its hold for a moment as the dancers struggle to find their literal and figurative voices.

Make/Believe has all the fundamentals of a great performance; there’s drama, character and a refusal to let the audience get away with passivity. Have no fear of (or hopes for) being asked to get on your feet, but don’t think you’ll escape emotionally either. This show will not let you off the hook and the only thing more devastating would be if they were to shut the audience out. Witnessing these performers struggle to communicate engenders pity, horror and fear as well as delight, sympathy and laughter. The physical, electronic and emotional obstacles that choke back words and make speech inarticulate let through just enough meaning to send ripples of laughter through the audience as we recognize a phrase out of that special garbled language in which only dental care workers and drive-through clerks are fluent.

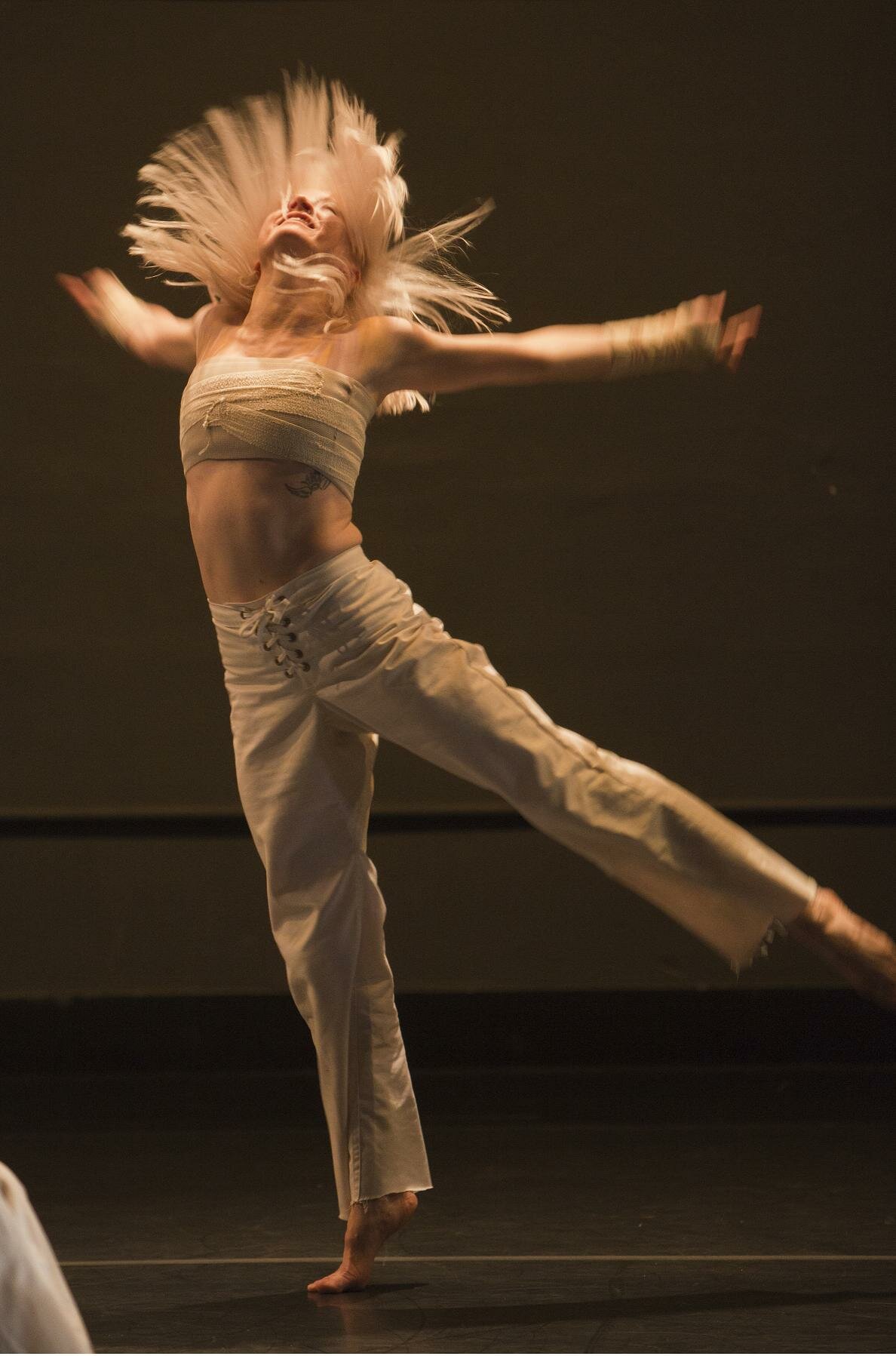

In addition to Kraft’s composition, sounds come from the dancers, who carry microphones in their mouths, around their necks, and between their legs. Sometimes they actually hold them in their hands, yet even when speaking directly into the microphone the dancers work hard to disrupt our understanding of the sounds and their sources. This draws attention to the non-vocal sounds of limbs and breath. The movements make their own music only to have that music overwhelmed by the amplified soundscape, suggesting that the sound derives from the movement rather than the conventional reverse. With the music at a volume that becomes palpable the dancing takes on the silence of distance.

With the exception of a few lifts, both graceful and harsh, and one extraordinary leap, the movements remain grounded and often focused on the torso. Minimalist unison quartets go from languid to fierce, followed by staccato sections with rapid emotional shifts, before breaking into alternating duets and a few solos.

The dancers’ roles are often highly gendered and sexualized. The women take prominence as characters but the men frequently stifle the women’s voices. Though this dynamic is subverted in a variety of ways these scenes create some of the biggest emotional impacts in the performance. The violence and intimacy of some movements inspires questions of who is in control amongst the dancers, in the performer/audience relationship, and between the individual dancer and her own voice—to say nothing of the technology that keeps threatening to gag and garrote.

There is one really deafening moment during the performance, so it’s helpful to take note of the earplugs available next to the programs as you enter the Griffin (I didn’t take a pair but came out okay: any tinnitus that followed didn’t make it to curtain call).

The technical side of the production is stellar. Alex Gagne-Hawes’s lighting includes extraordinarily sharp focus and extreme shuttering, while Kraft’s soundscape, could almost stand alone as a performance.

This is not dance made purely for an esoteric dance-knowing crowd. It’s accessible without pandering, moving both intellectually and emotionally, and playing here for far too short a run: In addition to yesterday’s opening-night performance, Make/Believe is presented tonight and tomorrow.