We’re all gonna die. Well, maybe not Raymond Kurzweil, but the rest of us, after our allotted span, will die. This is business as usual, and it’s one reason why global crises–no matter how terrible–that look to be more than a few generations away get treated so abstractly, while the more pressing matters of today–gay marriage, public access to birth certificates, Kindle vs. the iPad–monopolize our attention.

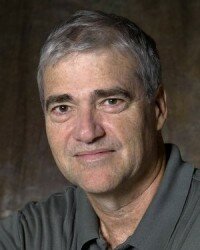

University of Washington professor and paleontologist Peter Ward is the author of sixteen books (many about mass extinctions, which area has been a career-long focus). He’s that rare breed of research scientist who can also combine directness with a personal style that makes his books a pleasure to read, despite, you know, the relative downer of mass extinction.

But his last three books–Under a Green Sky, The Medea Hypothesis, and most recently The Flooded Earth–argue with growing intensity that we underestimate the climate change to come, putting hundreds of millions of lives, if not billions, at risk. As Ward emphasizes, despite all the argument over greenhouse effect models, we already know what happens when carbon dioxide levels exceed 1,000 ppm–the ice caps melt:

As a paleontologist who has had to professionally study the effects of rising and falling sea level from far more ancient times than the time of humanity, I know that we are not merely speculating through cloudy crystal balls; we can see from the past what we face in a future we have created. The geological record holds a rich history for scrutiny. This book is based on the fact that the earth has flooded before.

Ironically, though he commands an audience other scientists only dream of–you’ve likely seen Ward on PBS, or might even have seen him unsettling the audience at TED (see bottom of post)–the exposure has mainly given Ward insight into the Cassandra effect. If your view of a calamity is sufficiently horrific, it gets described as a “dystopian vision,” which makes it sound like a literary threat. A year after publication of The Flooded Earth, he sees a “complete lack of action, a complete lack of conversation” on the realities of climate change.

Ironically, though he commands an audience other scientists only dream of–you’ve likely seen Ward on PBS, or might even have seen him unsettling the audience at TED (see bottom of post)–the exposure has mainly given Ward insight into the Cassandra effect. If your view of a calamity is sufficiently horrific, it gets described as a “dystopian vision,” which makes it sound like a literary threat. A year after publication of The Flooded Earth, he sees a “complete lack of action, a complete lack of conversation” on the realities of climate change.

When you talk with Ward, what’s most disquieting is that he’s not at all a doomsday preacher, obsessed with the morbid thrill of worrying over worst-case scenarios. The more spectacular effects that he’s talking about play out over centuries, if not millennia–it’s just once their momentum is established, they will play out, whether we come to realize our mistakes or not.

When we spoke with him at his office recently, he was chuckling over a recent call from a screenwriter who was trying to dramatize global warming. The writer wanted a scenario that would generate 10-foot floods in three days, because anything less doesn’t look that catastrophic, recounted Ward. The writer needed to kill a lot of people in a hurry.

“I thought, ‘Are you insane? Six feet of flooding is going to cause the greatest famine in human history. It’s going to take out all the deltas. Deltas are really delicate,” said Ward, explaining that delta formation requires quiet water, protected from waves and tides, so that river-borne silt can accumulate in place.

California’s Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta grows “asparagus, pears, corn, grain and hay, sugarbeets, and tomatoes, which bring in over $500 million annually,” reports California’s Department of Water Resources. Thanks to subsidence, the area is in danger of flooding with saltwater if its 1,100 miles of levees fail, ruining both cropland and freshwater supplies. Ward added that the risk “isn’t just the flooding, it’s the infiltration of groundwater by saltwater”: A one-foot rise in sea level can result in hundreds of lateral feet of salt infiltration. (Globally, the sea level has risen about eight inches over the past century.)

The great Mekong Delta comprises some 15 thousand square miles, almost all of which lie more than 16 feet below sea level. It accounts for about half of Vietnam’s rice output, and Vietnam is second in the world in rice production. The Delta is home to over 17 million people.

Talking about survival, Ward said, “There’s two things, there’s making it–and making it happily.” He believes it’s going to take “a couple of huge mortality shocks to wake us up” to climate change, on the order of millions of lives lost, from global famine as the world’s deltas are retaken by the sea. “We’re already dependent on bumper crops every single year,” Ward said ruefully, pointing to food riots from what may come to be seen as minor rises in prices.

“The simple answer is, there’s too many humans. We hit seven billion last week,” Ward said, pointing out that giant disasters are not more frequent per se, but are the result of more people in harm’s way. “Anywhere there’s flat land near water, houses go up,” he noted, adding that the population hit by the December 2004 tsunami had doubled in size since the 1960s. (You want a real dystopian vision, read The Wind-Up Girl recommended Ward.) Don’t get him started on Bangladesh.

Again, Ward’s prognostications aren’t based on the wildest scenarios out there. He told Salon last year that:

The most extreme (that you can put real scientific confidence in) is 5 feet by 2100. The most conservative at this stage is slightly less than 1 meter, or about 2.8, 2.9 feet. The best, most levelheaded predictions and models comes from Stefan Ramsdorf, just outside of Berlin in Potsdam. He’s now saying at least 3 feet by 2100, with 5 feet not out of the realm of possibility.

That rate of change is alarming to someone who works in geologic time–and here it’s worth mentioning that “runaway warming” would over millennia bring rises of hundreds of feet–but in today’s world the screenwriter is right: A three-day catastrophe is more likely to get our attention, even locally, in environmentally conscious Seattle.

While we study the acidification of Puget Sound, Ward, who used to be a professional salvage diver, sees an even greater example of the danger we’re in in the oxygen-depletion of the waters of Hood Canal. Enough phosphates and nitrates are making their way even into the Canal’s tidally flushed water to create algae blooms that suck up all available oxygen. When the algae dies and sinks to the bottom, it feeds microbial life that produces hydrogen sulfide.

“Seagrass is the real canary in the coal mine,” mentioned Ward. “Seagrass is easily knocked out by increased hydrogen sulfide, and it’s not coming back.” (On a related note, the UW’s Claire Horner-Devine is studying how climate change is helping non-native eelgrass to supplant the weakened native species.)

That layer of hydrogen-sulfide-friendly sediment is also the result of non-native species we added to the Northwest. As people settled near water, they chopped down the needled forests, and planted broad leaf trees that seasonally are huge leaf-litter bugs: “You are just filling up this place with biological matter. If you go down and core the sediment, the last 200 years it’s all just black.” Hydrogen sulfide build-up over the long run, believes Ward, is a serial killer of plants and animals worldwide.

Meanwhile, Ward, who lives on top of Sand Point, doesn’t think that even the rainy Pacific Northwest will escape the stresses of a diminishing freshwater supply. “If the temperature warms one or two degrees centigrade here–but it’s going to be way more than that, it’s going to be four or five degrees–we don’t have a snow pack,” he predicted. Without the snow pack, Seattle’s famously dry summer and fall would make for severe water and electricity restrictions, as we’ve already discovered from years the snow pack was simply low, rather than absent entirely.

Ward’s experience as a climate change Cassandra hasn’t affected him the way you might expect. We found him enthused about his application for interdisciplinary graduate research grants. “Why do we have such miserable science literacy in America? It’s because scientists are not rewarded to go out and talk directly to the public,” he argued. “The big policy decisions are all science-based.”

He wants to subvert the “science first, journalism second” paradigm by teaching graduate students to tell their own story: “I want to create a new graduate student who’s a scientist-journalist, same person,” Ward said. With knowledge of production techniques they wouldn’t have to wait for two guys from The SunBreak to hunt them down for an interview. They could write it, film it, record it themselves. More people would gasp in shock as they heard what climate change is bringing.

Do people need scaring? “Yeah!” exclaimed Ward. “Over and over and over and over. Because we forget. We put it away.”