It’s been a while since McCaw Hall, home to Seattle Opera as well as Pacific Northwest Ballet, has had the curtain rise on a production as glamorously grand as Alexei Ratmansky’s Don Quixote (through February 12). The scenic and costume design by Jérôme Kaplan brings you echo-y stone-walled villas, sun-drenched plazas, barren plains, and lively taverns (with the assistance of James Ingalls’ painterly lighting). Giant projections at the rear present glimpses of towns, sad moons, and windmills. In the foreground, everyone is brightly costumed in sashes and skirts and capes and severe tutus that suggest lace and mantilla.

This is of a piece with Ratmansky’s choreography, which adroitly balances, against the ballet’s traditional fetish with technique, a sense of place, inhabited by living people. His crowd scenes are a marvel of details, as little groups form and mingle–it’s perhaps a way of staking out a middle ground between his choreographic forebears in quixoticism, Marius Petipa and Alexander Gorsky. (The latter’s Don Quixote d’après Petipa, was not, sniffed Petipa, but full of “meaningless innovations and changes.”)

Here, the choreography is indicated as Petipa, Gorsky, and Ratmansky, though as Ratmansky admitted in a pre-rehearsal talk, “I’m mad at all the ballet historians” for not having documented much of the Don Quixote choreography at all. Ratmansky could only find notation for “one tiny scene” that “seems to have nothing to do with what’s known of the ballet.” Otherwise, he’s relied on the ballet form of the game of Telephone, where dancers and stagers transmit the work personally.

His contribution, he said, was to augment the prologue so as to give the audience more time with Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, and giving groups “character,” so that they aren’t simply standing there watching the soloists perform. That’s important because–perhaps surprisingly–this isn’t really an opera about Don Quixote, no more than Massenet’s opera follows that closely Cervantes. “It’s about the beauty of classical dancing,” explained Ratmansky, and the exuberant ability of the young.

Here, Don Quixote is an aged, unreliable observer of life’s ballet (as performed by Tom Skerritt, eager to bring justice, quickly smitten, and given to almost Biblical hallucination). The mimed comedy of Quixote and his rubbery-faced squire, Sancho Panza (Allen Galli) is only occasionally the focus; more often, you are following the travails of the young lovers Kitri (Carla Körbes, opening night) and Basilio (Karel Cruz), or celebrating a kind of Spanish cultural festival featuring toreros and matadors and knife-dancing.

Everything is an occasion for a dance, and by the close, you are almost over-stuffed with petit pas, pas de chat, pas de bourré, grand jeté, fouetté…. You’re dizzy with pirouettes. Can they possibly be reappearing for more? The story has been long ago left behind, there is only this paroxysm of dance, building from the precisely pointed feet stepping across the stage in Act I, to the endless pirouettes and leaps of Act III’s conclusion. The audience is gasping audibly.

Depending on when you go, you will see a different Don Quixote, as different soloists will bring something different to their performance. Early on at opening night, Körbes and Cruz were not perfection, technically–admittedly those one-handed lifts are staggering–but they caught fire as a duo in the second act, almost leaving a trail of sparks across the stage. I’ve not thought of Körbes as all that fiery a temperament. Maybe her raven-haired gypsy wig did the trick, because she and Cruz generated that duende elusive on a ballet stage.

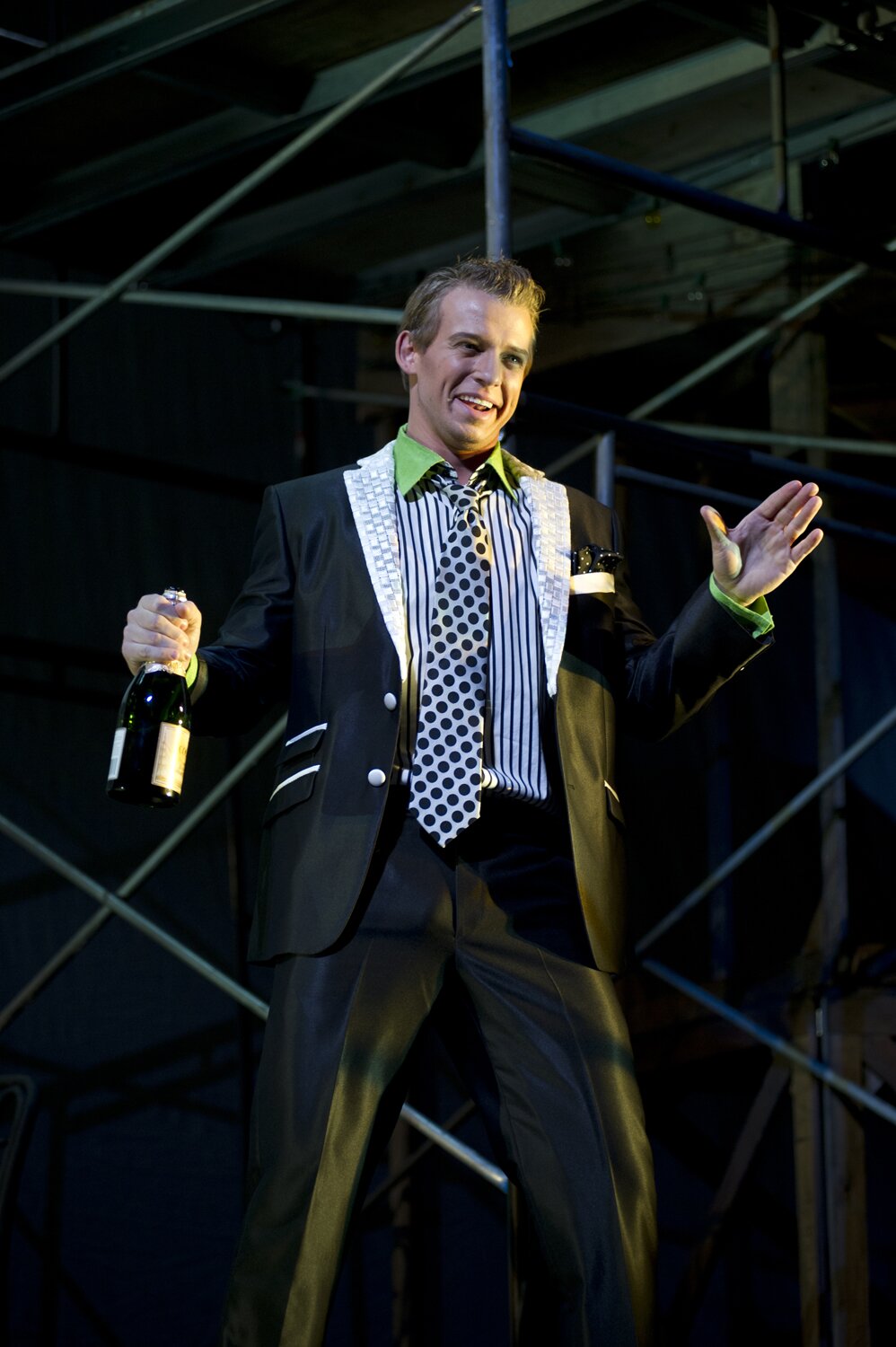

Jonathan Porretta’s Gamache, the wealthy suitor that Kitri’s father wants to marry her off to, doesn’t dance, but he steals scenes consistently–it’s hard to take your eyes off him. Porretta and Ratmansky skewer the peculiarly Spanish fop–his obsession with appearance, machismo of convenience, and pettiness. Audiences may find that ensembles–the toreros were not overly crisp on their lines–improve over the run, but there’s nothing to complain about in Mercedes and Espada (Maria Chapman and Batkhurel Bold) or the three beautiful dryads who appear to Quixote (Jessika Anspach, Lindsi Dec, Laura Gilbreath).