For many of us, opera can be a somewhat remote experience. We sit far away from the singers in a large hall, and while we can hear every emotion in their voices, we sometimes have a hard time seeing emotional nuances in their faces. But Vespertine Opera Theater’s production of Les Mamelles de Tirésias (The Breasts of Tirésias) is up close and visceral at Columbia City Theater (last show tonight at 8 p.m.).

Based on the surrealist play of the same name by Guillaume Apollinaire, the opera takes place in the fictional town of Zanzibar, in the south of France. A woman named Thérèse, fed up with her husband and womanly expectations, finds that she’s turning into a man (Tirésias). She becomes a famous general and leads a charge against childbirth and children. Meanwhile, her husband decides that since his wife has become a man, c’est logique that he must be a woman, and proceeds to birth over 1,000 children in a single afternoon.

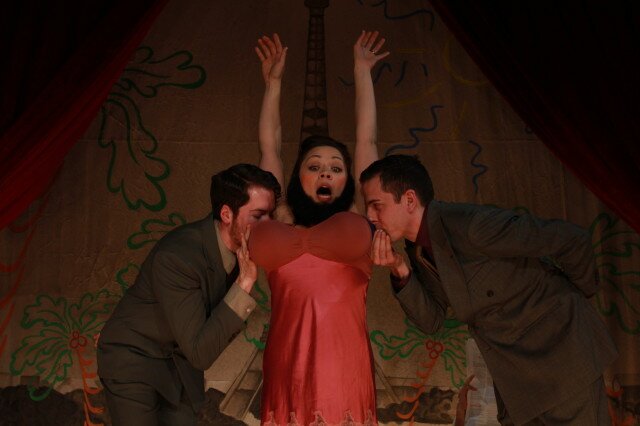

Full of double entendres, word play (the relationship and translation between French and English is a fertile field), and a playful disregard of logic and sense, the story will amuse you. The singing will also please you; the small cast is full of young rising singers. José Rubio, The Husband, has quite a powerful voice – at times in that small space it was like he was standing right next to me, singing in my ear. He also has a marvelously elastic face, making the more ridiculous moments hilariously funny.

Tess Altiveros, as Thérèse/Tirésias, also did a fabulous job. She handled the non-linear and wide-ranging part with finesse, and her voice warmed in Act II. As The Director/The Gendarme, Daniel Oakden did a fine job (he, too, is blessed with an expressive face). They were supported by a superb chorus, some of whom stand out for named roles or a few lines sung from the audience.

Dan Wallace Miller’s direction is apparent in every scene. He does a great job of emphasizing the farce without going over the top, allowing the music and the libretto their fullest expression. Playing a part in the music’s expression are co-music directors and pianists Dean Williamson and David McDade, who took turns conducting at key moments from the pianos. They played seamlessly together, as well as supporting and balancing the singers.

Lighting and co-set designer Marnie Cumings lit the stage and the rest of the house (when the singers were in it, that is) with precision. Sets, co-designed with Miller, were minimal but expressive of the setting – metal palm trees and a backdrop by Christopher Mumaw made the small theater feel fairly tropical.

Geoff Rozmyn created three witty posters for Tirésias’s campaign against childbirth and children, rich and cartoonish and big audience favorites. Costume designer Savannah Baltazar presented a cohesive palate of color and era, and facilitated a few witty costume changes on stage. Also impressive was her design of Thérèse’s dress, which accommodated both natural and huge (unnatural, ballooning) breasts.

This production is a historical one, as this is its U.S. premiere. In 1956, Benjamin Britten became a big fan of the French opera, and discussed with Poulenc the possibility of performing it at the Aldeburgh Festival (co-founded by Britten). To suit the space, Britten and long-term collaborator Viola Tunnard arranged the opera for voice and two pianos. Tenor Peter Pears, stage director Colin Graham, and choreographer John Cranko produced an English libretto, and it was performed in June of 1958. It then disappeared, resurfacing only in 2011.

Edited by Emily Hindrichs, it was performed again in the UK in October of 2012, over half a century from its first performance. That version premiered here Tuesday night, and will be reprised tonight, Thursday.