“[Y]ou know, it’s a pretty straightforward show in terms of what it is,” said playwright Young Jean Lee about Untitled Feminist Show (at On the Boards this weekend; tickets). “People are either going to be like, that was fun, or they’ll say, that wasn’t experimental enough, that wasn’t feminist enough.”

Though it’s mostly wordless, except for a brief song, it reminded me in ways of Gertrude Stein’s seminal “Lifting Belly” poem, which has plenty of words, just not used in the manner with which you’re likely to be familiar. “As I say a noun is a name of a thing, and therefore slowly if you feel what is inside that thing you do not call it by the name by which it is known,” declaimed Stein on the issue. (Though she would also try, by sheer dint of repetition, to reach that moment you stare at a word, asking yourself if that’s how it’s really spelled.)

So, too, Untitled Feminist Show feels much more interested in the semiotics of behavior, of body, of identity — in transitional spaces and movements — with the intent of not letting you settle on firm ground to take up a fixed viewpoint. If it refuses to be (Derrida elbows his way inside the paragraph, shouts “Phallocentrisme!” and exits) serious about weighty things and their definitions, perhaps that’s because it’s joining a conversation where gravity and definitions are already well-represented.

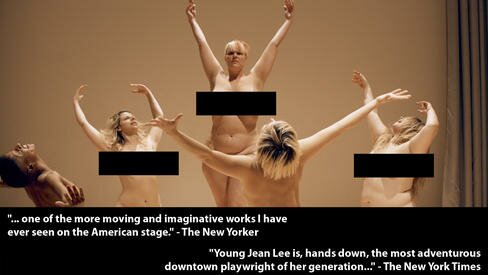

The show begins with breath, the sound of it in unison, as the performers slowly process down the aisles to the stage. They are naked. They are Hilary Clark, Becca Blackwell, Desiree Burch, Katy Pyle, Malinda Ray Allen, and Amelia Zirin-Brown. They all have different backgrounds as performers (digital program pdf), and are differently shaped, but they display that ease with nudity that people pretend is so outrageous among nudists — because we know the world requires clothes.

Young Jean Lee worked with choreographer Faye Driscoll (and director Morgan Gould, and her cast) to develop the show — the resulting movement vocabulary is sometimes purposefully banal, but at other moments it seems to go off like a camera flash, as when the performers partner each other and hold their partner’s hair back for them. A blenderized fairy tale segment set to classically plinking music features Zirin-Brown as a witchy Medusa who picks off a happy trio with pink parasols, one by one, by magically freezing them. They’re fed, with plenty of mimed-gore, to her misshapen, hungry Grendel (Katy Pyle), until the third refuses to let Zirin-Brown winkle away her protective parasol, and stabs her with it. The two eaten are freed from Pyle’s stomach just like Red Riding Hood from the wolf.

I saw that Becca Blackwell, the non-gender-conforming performer, was at first rejected by the two other parasolers, and it became a fable about feminists eating their young, and even the difficulty that trans people have had with hard-line feminists demanding, you know, proof you’ve checked out your copy of The Red Tent. (That’s a reference to biological imperative, rather than a suggestion that radical feminists love The Red Tent.) The show continues in a variety-style vein: Katy Pyle and Malinda Ray Allen dance a balletic duet, with pirouettes and lifts. The ensemble break down some rap-video moves (Chris Giarmo and Jamie McElhinney’s sound design captures every genre) with additions like “Moppin’ the Floor,” “Changin’ the Diaper,” and “Cookin’ the Dinner.” Zirin-Brown furnishes a pornographic-castration mime, winking jauntily, grinning lewdly, before singing sweetly.

Allen reappears for an extended vocal solo, singing “La la la” with great (albeit pitchy) verve to cackling from seats in the back. Hilary Clark rages to some heavy metal, and slow-motion parking-lot fight breaks out between Desiree Burch and Clark, bystanders egging them on. Becca Blackwell performs a gripping solo, moving from a mocking, burlesque “Nah nah nah,” to shadow boxing, kissing a bicep, and vocalizing something gut-deep. The ensemble impersonates a tribe of bonobos, luxuriating in skin-on-skin. No hold is barred. Someone’s foot ends up on someone else’s pubis. Raquel Davis’s lighting design never tries, really, to soft-focus anyone’s nudity — at times, she uses a searing white light to turn up the volume.

Throughout, a series of projections by Leah Gelpe plays over a white, lengthwise obelisk by set designer David Evans Morris. At times you don’t notice them, at times they feel perfect as a kind of radiation of what’s happening.

But what is happening? There’s plenty to chuckle or howl at, there’s tenderness and rage, but the show in refusing language Schrödingers away in its box, resolving and unresolving meaning. Is the rap “video” an on-the-nose feminist response, or commentary on a response? Is it empowering to see Clark and Burch slug it out, or is that machismo regressive? What about the rhetoric of performance nudity, of its authenticity? Should we bother to critique a utopic vision?

That analytic impulse is reflexive. But if you think about the show being bookended by first a fairy tale and last by what people are calling an “orgy,” perhaps there’s a directional arrow, pointing the way from childish belief in structures to genuinely childlike, undifferentiated openness. The stuff in between, in its valencies and ambivalence, is a function of having (Gertrude Stein’s distaste intrudes) a noun called feminism, a noun called feminist, a noun called woman. Untitled Feminist Show reminds you that we are not contained by words, or their arguments, but we often act as if we are.