At various times during his life and following his death, Paul Gauguin was described as an impressionist, post-impressionist, symbolist and a cloisonnist. If such classifications imply a unique versatility, don’t be fooled. Whatever the art historians say about the man, he had a single defining characteristic.

He was rootless.

No artist before or since, not even the enigmatic author Kurt Vonnegut, has ever had such a profound case of wanderlust. Now, a wonderful Gauguin exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum, “Gauguin and Polynesia: An Elusive Paradise,” puts Gauguin’s travels and travails into wonderful focus, played out against the art of the people he painted. Admission is free for SAM members and kids 12 and under ($23 Adults; $20 Seniors and Military with ID; $18 Student with ID and Teens 13-17). There’s a $3 discount on all tickets Thursday and Friday, from 5 to 9 p.m.

Drawing from many sources both public and private, “Gauguin and Polynesia,” which was organized by Art Centre Basel, is on view from February 9 through April 29, 2012. It includes nearly 60 paintings, sculptures, and works on paper, which are displayed alongside 60 major examples of Polynesian sculpture. It’s as fine a show as SAM has ever done: an honest measure of a strange and remarkable man.

Born in Paris 1848, Gauguin grew up in Peru. While there he was impressed, and moved, by the native arts, pottery, and costumes of the Peruvian people and the ancient Inca. His family moved back to France when Gauguin was seven years old. The family, and then Gauguin himself, moved around. Each time, Gauguin reflected that he was finally home, only to decide after a few months–in some cases years–he wasn’t really where he wanted to be after all.

He married in 1873 a Danish woman and moved to Denmark. He tried his luck as a salesman and a stock broker, and raised a family. But he never settled down.

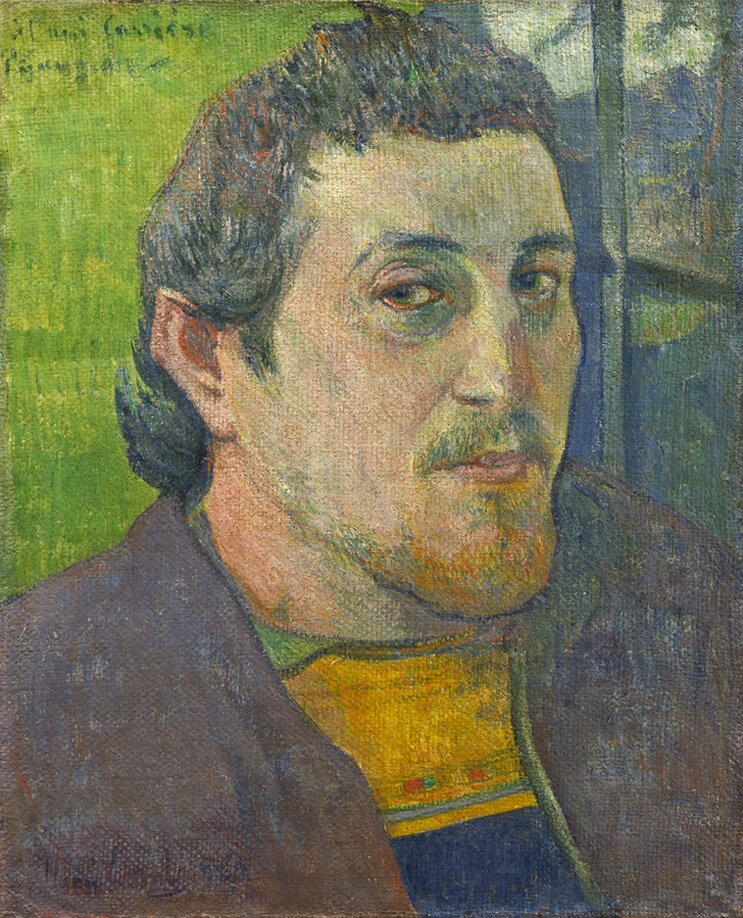

In 1888, he spent eight weeks in the company of Vincent van Gogh in Arles, where van Gogh hoped to build an artists colony. What happened over those weeks changed both of their lives. They had a complicated relationship, Gauguin the dominating bully, van Gogh constantly playing eager to gain Gauguin’s trust. It didn’t end well. Van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a knife or razor, fled to a brothel and cut off, in differing accounts, his full ear or just the lower lobe. (There is a wonderful Gauguin painting in the first gallery of the SAM exhibition where the artist does a lovely homage to van Gogh. Look for it, it’s one of the best in the show.)

Gauguin fled, and by 1891 he had left his family and set out for what he hoped would be the exotic worlds of Polynesia, stopping first in Martinique and Panama where he worked on the first iteration of the Panama Canal.

Then he set sail for Tahiti. And that’s where the SAM exhibition starts. The exhibition has been beautifully put together. The first galleries take the visitor from Gauguin’s departure from France to his arrival in Tahiti where, in conjunction with a government agency, he recorded the lives of the local population.

And it’s here that you see that the artist must have been shocked that the paradise he expected was long gone. Tahiti was first explored in the 1700s. Half-naked Tahitian beauties hypnotized early western sailors, such as the crews of Captain Cook’s ships. After those first stories got back, everybody who could go to Tahiti went.

Taking advantage of local customs and traditions, English, Dutch, and French sailors took Tahitian women as lovers. They spread venereal diseases far and wide. The native population declined. By the time Gauguin got there, missionaries were hard at work bring God to godless natives. Whatever paradise the artist wanted to find wasn’t there. Even the wonderful Tahitian Tiki statues were gone, burned by the missionaries.

The SAM exhibit tries to juxtapose those early, sad, disappointed paintings of Gauguin with magnificent examples of early Tikis and native sculptures. Intricate, beautiful, voluptuous, they give an idea of what Gauguin must have been looking for.

There is a poignant portrait of Tehamana (Tehamana Has Many Parents), Gauguin’s Tahitian mistress that says a lot about the artist’s hopes. She is presented in a missionary dress, but behind her are cryptic Polynesian carvings and writings. It also reveals Gauguin’s less savory side. The girl is 12 or 13.

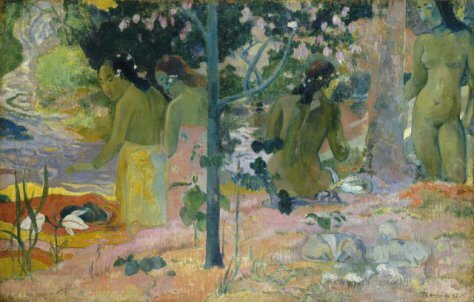

Gauguin returned to France, wrote a highly romanticized account of the islands, and struggled with his return to French life. He left his heart, it seems, was in Tahiti. But Tahiti left part of its tragic history in him as well. He had contracted syphilis. He went back. And this time, because the beauty he sought wasn’t really there, he painted dream paintings of an exotic world instead. It’s these paintings that form the basis of Gauguin’s reputation and lasting popularity, though few of them were sold in his lifetime.

And his proclivity for getting into scrapes with people, particularly officials, never ceased. He was run out of island after island it seems. One scrape, this time in the Marquesas Islands, where he put a kind of Polynesia sexual playhouse together, was about to lead to a prison sentence when, in 1903, he died of an overdose of morphine. He was a very old 54.

As with van Gogh, it’s hard to separate Gauguin’s work from his life. His sad story, his hopes, his realizations, his pyrrhic victories, his dissolution are completely presented in the SAM show. The exhibition lays out the simple truth of the artist’s life: a promise unkept is different than living a lie.

Special events associated with the exhibit include SAM’s after-hours Remix, on February 24 from 7:30 p.m. to 12:30 a.m. (Nonmembers $25, Students $20, SAM members $12) and a talk from Musée d’Orsay curator Stéphane Guégan on Gauguin, on March 8 at 7 p.m. (Nonmembers $10; Seniors and Students $8, SAM members $5).