Fans of operatic composer Richard Wagner devour and worship his works with an unabashed fervor normally endemic to Deadheads or Star Trek fans.

Wagnerians frequently travel around the world to view stagings of his operas, pore over hours of recordings of his compositions, and scarf up shelves of books covering Wagner’s life and creative output. This town’s done more than its share of stoking that devotion, too: Seattle Opera has built an international reputation performing the composer’s music-dramas (the company re-mounts its lavish staging of Wagner’s epic Ring Cycle this August).

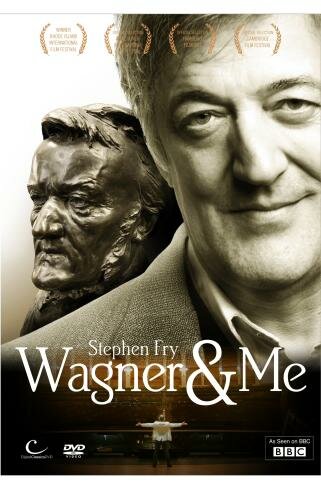

One of those self-confessed Wagner nuts, actor/writer/raconteur Stephen Fry, offers a guided tour of his obsession in Wagner and Me, a fascinating 2011 documentary opening at the Grand Illusion tonight and running through January 31. It’s a combination travelogue, biography, and love letter that reveals as much about its host/narrator as it does its controversial subject.

On the face of it, there’s ample reason for Fry’s adoration. Wagner stood as one of the most important creative figures of the nineteenth century, a composer of towering brilliance who essentially invented things like the leitmotif (one melody that recurs, in slightly varied form, throughout a musical work — think John Williams’ recurring ‘dum dum, dum dum da DUM dum’ theme surfacing in different tempos and instrument combinations throughout Star Wars).

Wagner also wedded that compositional mastery with an incalculably ambitious dramatist’s touch. His monumental four-opera Ring Cycle drew from Germanic and Norse mythology to explore the duality of humanity’s thirst for power and its need for love. Key pieces of the Cycle’s pocket universe were co-opted outright by generations of storytellers (including a chap named Tolkien), and the composer’s melodies have served as indelible soundtracks for everything from cinematic napalm bombings to Bugs Bunny cartoons.

Fry, it turns out, is one hardcore fan. He’s followed Wagner’s oeuvre passionately since the age of twelve, when he heard Tannhauser on his dad’s gramophone, and much of Wagner and Me follows the actor’s first trek to Bayreuth. The South German town serves as “Stratford-upon-Avon, Mecca and Graceland, all rolled up into one” for Wagnerians, housing a grand Opera House built for Wagner by King Ludwig as well as the composer’s gravesite.

Wagner fans should find much to enchant them throughout Wagner and Me. The movie provides a brisk Cliffs Notes on the composer’s life and career, and it frequently hauls out eye-popping vistas in Germany, Russia, and Switzerland. There’s no denying the power and potency of the music on display, and Seattle Opera fans will surely welcome glimpses of noted Wagnerian singers Christopher Ventris and Linda Watson, both of whom performed in the company’s Parsifal in 2003.

Wagner fans should find much to enchant them throughout Wagner and Me. The movie provides a brisk Cliffs Notes on the composer’s life and career, and it frequently hauls out eye-popping vistas in Germany, Russia, and Switzerland. There’s no denying the power and potency of the music on display, and Seattle Opera fans will surely welcome glimpses of noted Wagnerian singers Christopher Ventris and Linda Watson, both of whom performed in the company’s Parsifal in 2003.

Fry’s been given impressive access to the inner workings of the Bayreuth Wagner Festival, and he makes the geeky most of it, whether he’s waxing rhapsodic during rehearsals of Die Walkure or playing the opening chords of Tristan und Isolde on Wagner’s personal piano.

But there’s an exceptionally ugly 800-pound gorilla in the room in the form of Adolf Hitler, whose worship of Wagner tainted (irrevocably, many believe) the composer’s stirring compositions. Wagner and Me goes from simply engaging to quietly riveting when the Jewish-descended Fry addresses the stench of Naziism that continues to hang over the music, as well as the composer/dramatist’s vitriolic anti-Semitism.

Fry’s openly disquieted by both (having lost relatives in the Holocaust), but defends the art in the end, refusing to let the transcendent brilliance of the music be corrupted by racism or the Third Reich.

That astonishing music — and the insights of conductors and artists who’ve helped keep it alive — bolster that idealistic stance, so when Fry attempts to rationalize Wagner’s personal and ideological ugliness, he can’t help but sound a little naive. Yes, Wagner was a creative genius, and an artist doggedly committed to his muse. Yes, he lived in an era rife with casually-accepted anti-Semitism, and much of his prejudicial venom may have been born from personal jealousy over the financial success of his contemporaries, Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer (both Jews themselves). But Fry’s assertion that the person most hurt by Wagner’s anti-Semitism was Wagner himself feels like a futile attempt to find some shred of personal decency in an already-unlikeable (and unrepentantly prejudiced) human being.

Leave it to one Wagner scholar, author Chris Walton, to balance admiration with a refreshing gust of practicality. Wagner “may have been a nasty little man, and a nasty anti-Semite,” he states, “but that doesn’t make his music any less supreme.”