Annie Dorsen’s A Piece of Work (formerly known as False Peach) came and went from On The Boards last weekend but the conversation goes on — at least it has at Slog, and between this critic and his editor. As I submitted my review I summarized my impressions. This led to a discussion of the show, its intentions, achievements and potential. An edited version of that discussion follows.

SDW: I didn’t much enjoy the show — at least not emotionally. Intellectually I loved it and in no small part because I felt like it failed kind of spectacularly as theatre. This is all the more interesting to me because it feels very close to success. A bit more humanization one way or another could have brought it together.

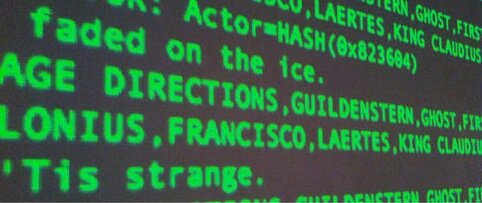

MVB: I talked to Annie Dorsen [the show’s creator] in advance but still wasn’t quite sure what to expect. It’s also a hard show to review in that the audience will see a different thing every night, as the algorithm reorders itself.

It felt a bit unfinished, and in need of tuning, as a piece. I think the algorithm was accidentally dropping names and scene IDs.

But the main thing I got from it is its resistance (as you noted) to telling me a theatre-story in any way. It was a bit like “an alien writes a play after reading Hamlet.” The alien has no idea about plot structure or character or relationship, all it can do is see word patterns: sets of prepositional phrases. Phrases that being with “O.” It seizes on “favorite” phrases to repeat, like an autistic person sometimes enjoys echoing things. It has a set of literal associations with set direction.

Dorsen talked a good fight about Hamlet as this ur-humanist text, and how this might redress that illusion of personal agency, but I think in fact you could walk out of it feeling a bit affirmed, as a humanist, that there is something more to consciousness than RAM and subroutines.

The failure of the piece as theatre I think rests on the context for it — if you include Dorsen & Co. in, then it’s a story about this attempt to present an algorithmic performance, and the inability of their creation to connect with 95 percent (?) of the audience. As a performance that you just walk in to, the failure is more obvious. You have to understand what is being attempted to “get” it on any level with emotional stakes. I like your notion [in the review] of an installation — what makes the creators think a computer has any interest in a set running time?

That reminds me, I meant to reference David Ives’s Words, Words, Words in which three monkeys (named Kafka, Milton, and Swift) are left in a room with typewriters to see if they’ll eventually write Hamlet. (You really think the percentage of disconnected in the audience was as high as 95 percent?) I was also fascinated by a sense that many thought Scott Shepherd [the lone actor to appear on stage, and then only briefly] was about to say something, and might not have entered for applause but for another scene just before the crew joined him.

Ha! I wasn’t thinking of Ives, but I definitely had a monkeys/typewriters association.

I may be exaggerating. The OtB crowd is famously tolerant of experiment, but I didn’t get the sense that most people were anything but puzzled by it. I think they probably wanted Shepherd to say something, at the close, to be human.

Neurologically, it’s an interesting experiment, because it frustrates the if-then “narrator” in everyone’s head that typically makes sense of things. It’s a bit Zen: boredom and frustration are cultivated as a way of turning off the monkey-mind. After peak boredom, the mind is more associative, less linear, more accepting of this “random” walk through a text.

It still may not amount to much; people have different interests, and this monkeying with consciousness may not rate that highly.

I feel like this show is more successful run as an experiment, asking people to record how they interact with it. Give them a survey on the way in. Seattle would get a kick out of that if they felt they weren’t being messed with.

I’m interested in your point about experimental theatre as an experiment in the double blind sense. Do you think the neurological experiment side of A Piece of Work would have been as interesting had Shepherd delivered the piece in its entirety? What if the only change were that Shepherd delivered all of the vocalizations instead of the computer-generated voices? Also, do you know if Shepherd was repeating lines delivered in his ear from the computer? What’s his role in this? I feel like his performance mostly served to highlight the non-theatricality of the rest of the performance.

I love your notion that the audience wanted him to say something, to act. I want to believe that this was intentional on the part of Dorsen, et al.

I think people would respond much more readily to the idea of a survey than a “talkback.” It’s weird, but people love being in experiments, so long as they know they are contributors to them.

Yeah, I think as far as frustrating that sense-making compulsion goes, plenty of plays already accomplish a similar thing with actual actors. Had Shepherd continued with gibberish, it would have gotten to people as well, just maybe taken a little longer. It’s when the play is all-computer that you realize you have to abandon all hope. :)

That said, I think Annie was trying for other effects by computerizing the space — I know she had this notion of the Hamlet text itself as a ghost of theatre, and if you step back, you can see that: sounds, lights going on and off. Is it a dramatic idea? Maybe not so much.

Re: Shepherd, she said something to me that was a (it turns out rare) emotional response, which is that sometimes (like with the chatbot play) she gets the sense that the bots are so close to thinking…that they’re trying really to say something, but fail, and it’s sad. Knowing of course that she’s investing them with agency, etc. But I felt like Shepherd’s role underscored that duality — a human actor who can’t quite make sense.

—

What about you, our readers; what did you think of A Piece of Work? Did you make it to the end? Did you walk out? Did you hope that Shepherd was about to speak when he returned to the stage? Did you relish every “O” like Ives’s monkey, Kafka, who types page after page of the letter K? Did the algorithms create a more perfect Hamlet on Friday or Saturday night? Would you like to participate in a post-show survey? Now’s your chance.